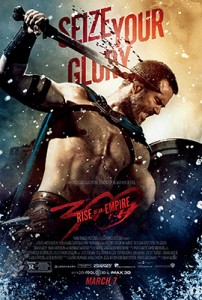

300: Rise of an Empire — The Real Story

Posted on March 6, 2014 at 8:00 am

This week’s release “300: Rise of an Empire” is a highly fictionalized version of a real-life episode in ancient Greek history that included a massive sea battle. It is a “side-quel,” depicting events that occurred around the same time as the famous battle covered in the first “300” movie.

This week’s release “300: Rise of an Empire” is a highly fictionalized version of a real-life episode in ancient Greek history that included a massive sea battle. It is a “side-quel,” depicting events that occurred around the same time as the famous battle covered in the first “300” movie.

In 480-489 BC, King Xerxes of Persia was determined to conquer Greece. In preparation for the next surge, he had his people bridge the Hellespont, the present-day Dardanelles, with two bridges were supported by ships as pontoons, with a the causeway laid across them. When they were destroyed in a storm, Xerxes ordered the designers of those bridges executed and that the Hellespont itself be given 300 lashes as punishment. Xerxes was making progress when a Greek slave was sent with a message intended to deceive him — he told Xerxes that the Greeks were weak and not able to oppose him. Historynet.com says:

On the morning of September 20, 480 BC, the main body of the Persian armada, about 400 triremes, moved toward the showdown. Xerxes sat on his golden throne high atop the contested area and watched the battle develop.

The Greek fleet was arranged from the Athenians on the left of the line to the Corinthians to the north, covering the Bay of Eleusis, the Pelopponesians on the right and the ships of Megara and Aegina in nearby Ambelaki Bay. The majority of the Greeks’ 300 triremes were hidden from the approaching Persians’ view by St. George’s Island. To draw the enemy well into the shallow water and narrow confined around Salamis, Themistocles ordered the 50-ship Corinthian contingent to hoist its square sails and feign retreat. Once the Persians were drawn in, the Greeks, in ordered line, would surround them. The Persians’ greater numbers would be no advantage in the narrows. Even worse, they would have no room to maneuver.The Greeks began to sing a hymn to the god Apollo as they struck the Persian vanguard in its exposed left flank. When the commanders of the leading Persian ships realized that they were trapped and began to backwater, the caused a tremendous crush of confusion, because those ships coming behind them had nowhere to go. Aeschylus, remembered as the father of literary tragedy, fought both at Marathon and Salamis. He later described the scene as similar to the mass netting and killing of fish on the shores of the Mediterranean: ‘At first the torrent of the Persians’ fleet bore up: but then the press of shipping hammed there in the narrows, none could help another.’

The Greeks kept outside of the tangled Persian mass and struck virtually at will. The Persian ships seemed more suited for action in the open sea-they were larger, sat higher in the water and were loaded with approximately 30 marine infantry or archers, as opposed to 14 aboard each Greek ship. Therefore, the top-heavy vessels fell easy prey to the bronze rams of the Greek triremes in those confining waters.

The Phoenicians in Xerxes’ fleet broke under the relentless Greek pressure and many of them ran their ships aground. Several of those Phoenicians hurried to the great king and said that the Ionians were the cause of their defeat. Xerxes had watched the Ionians perform well and ordered the Phoenicians beheaded for lying about their allies.

The battle continues to be studied by those who care about military history and strategy and it continues to capture our imagination thousands of years later.