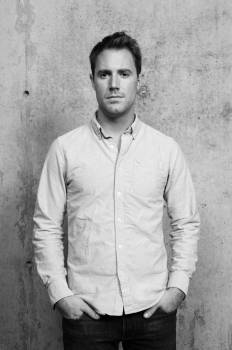

Interview: Keegan DeWitt

Posted on August 30, 2016 at 3:23 pm

Keegan DeWitt is a versatile and sought-after composer who has worked on a remarkably wide range of television and film projects. Keegan DeWitt is a versatile and accomplished composer, who has strengthened many stories across film and television. This October, his music will heighten the drama of HBO’s highly anticipated series, “Divorce,” starring Sarah Jessica Parker, Thomas Haden Church, and Molly Shannon. He wrote the scores for eight Sundance Film Festival selections including the current release “Morris From America,” starring Craig Robinson. I was very glad to get a chance to talk to him.

Music is a very important part of the storyline of “Morris in America,” with key scenes including rap and electronic music. How do you approach that?

It’s easy because Chad Hartigan and I have been friends since we were teenagers. I work with some really interesting people but it is great to be able to work with a close friend, especially because Chad and I grew up talking about movies and getting excited about movies. So the process of making a movie with somebody you went through that with is that much more rewarding. And this was one especially cool. One day Chad has this idea of, “Let’s figure out a way to make an international co-production in Germany with Americans and Germans,” so I was like “Okay,” and next thing I know, me and him are riding bikes across the park in Berlin to go to the production office and score the movie which was so great.

And then musically, it’s a tough double-edged sword in that when we sat down, we had to make so that when people watch it they will have no idea this is a score. We really wanted it to feel like the hip-hop stuff was totally authentic, real hip-hop. And the EDM with exactly the same. And so on and so forth.

And then when the score stuff happened, it just was like breathing in the film and it all felt really organic and at no point did you notice it. That’s an especially tough gamble when it is such a music-centered film and there is a ton of music in there.

It was a fun project in that I had to roll up my sleeves and go, “Okay, how do I do each of these types of music?” It was also hard because there are racial implications in it as well, just like Chad as the writer and director creating this narrative. I felt this huge spotlight on myself to not be just a white person imitating hip-hop.o for me I was really encouraged when I sat down to write like that when he’s 14. But I clued into what first got me really excited about hip-hop when I was a teenager which was the melodic stuff like De La Soul and Del the Funky Homosapien and people like that. The hip-hop that the character Morris creates is sort of goofy, like a goofier hip-hop that somebody who is coming from a slightly more naïve innocent place like Morris could get into. And so for me that was my little slot in the door. I was like, “Ah, I got it.” I could sneak in with this because this is authentic in my experience and I also think it could be authentic to Morris’ experience.

And we also thought that it was an important thing to choose hip-hop that was somewhat fun so that we weren’t trying to comment on or make things seem gritty. The thing that I thought was so rare about the script is actually like it’s just so thick with love and curiosity and all those things. And it’s like Chad said, “If you want that really gritty dark person, go see every other movie about what it’s like to be a bad teenager.” I think that’s really true. And I am always drawn to what somebody wants to do something that’s like very pop. And so I was excited to be able to do that on this as well. And then on that note also to make the electronic music feel scary too. We tried to make it really loud and aggressive so that when he’s walking up to that club on that night you feel that rock in his stomach that you would feel if you were stepping up and could just hear the pounding music from inside.

So, now that you’re working on the new “Divorce” television series, how is it different to approach a TV series versus a movie?

I was lucky on “Divorce” because it’s HBO so it super creative and artistic to begin with. And also with this show, because everyone loves Sarah Jessica Parker and Sharon Horgan the creator, there is just a reverence for them in the work they do that there is a lot of space and a lot of grace for the creative process. When I got there they pretty much shot two-thirds of everything and we really got to spend like three months just being creative.

I don’t think it’s often on a TV series that we are a month into postproduction and it feels like hanging out on a Saturday evening. We are all just talking about music and I would play them little things and they would get excited and be like, Oh, what’s the name of that type of drum?” Yeah, the Bodhrán, okay. Bodhrán, let’s go crazy on that and experiment with that. So we did like a whole week of crazy Bodhrán music and then did crazy flute music because that show is really like in the 70’s and Jethro Tull and stuff like that.

I’ve been really lucky in that way. I’ve done other stuff where you jump in and you are just creating music and you are like, “I hope that makes sense.” But with this, we really did get to begin almost as if it was a movie and go through each episode and really choose to be adventurous. I was just really lucky, especially for a relatively younger composer, to be able to be in a room that’s got that many talented people. It was an opinionated room for sure and it was a competitive kind of “Can I meet these expectations?” But that’s always exciting as long as the people are really intelligent and excited as they were.

The thing that I know that SJ fought for and resonated with me was that it’s really important that as an adult so often things can be super dark or super sad and then in the same moment totally farcical. We had to figure out ways to mix extreme happiness with awkwardness or extreme sadness with moments of real tenderness or even silliness. And so I tried to make sure that I represented all ends of the spectrum and even if I would stay on the silly side of the spectrum, there was a real humility and a real intelligence to it and then it if was sad, it still felt a little bit like off kilter, a little bit ridiculous.

Thomas Haden Church is so good in the show. He’s so funny and has such heart. One minute he’s sabotaging Jessica Parker’s life but in the other minute he’s like this dad whose family is falling apart and he’s desperately trying to keep it together. So as soon as I walked into it I knew this is an intelligent project and I really had to make sure that I continued to meet that in terms of not giving them a cue that included all of the moods and emotions.

Do you compose on the piano? Or a computer keyboard?

My main instrument is piano to compose on but this was a crazy experience in that one day we were talking about me maybe going into the project and then the next week I was flying of the New York and literally composing in the post-production office. I was just trying to be a ninja with the computer as much as I could. So there are lots of saxophones and organic things that I try to really add some humanity. And every night I would walk to the subway and be calling a bunch of people that I know all over the United States to be like, “Hey, can you send me a voice memo of you playing this theme on the saxophone but sort of make a long?” And every morning I would be getting email dispatches from players around the United States that I would then bring in and chop up and have to work on the slide to get things together.

I always say I could divide it and these two camps; the people who are great with computer and the people who are purest with real instruments. And I’m always fascinated by what if you send me a really crappy recording of your saxophone where so it feels really gritty and interesting and breathy and then I’m going to take it to the computer, re-pitch notes of it, cut it in half, slow it down, put it in double time and then once I do that with five different instruments at once it’s this really cool mix of both of those things.

I always try and remember a limitation is not a limitation. It’s like a gift, it’s a creative gift. So this thing was like how do I compose music that I have to audition in high-pressure circumstances with like 15 minute turnaround times in a production office in Greenpoint on a laptop? It’s time to treat this like it’s a scrapbook and I’ve got a bunch of scissors and paste.

Then we sit down with Sharon and SJ and everyone. It was this challenge of one group wanted a lot of the Bodhrán because it was chaotic and interesting and crazy and the other one was flute music and I was sort of jokingly at one point, “Do you realize that when you mix Irish drums with flutes you’ve got ‘Braveheart.’ I turned the flute into a saxophone because it’s got a little bit more comedy but also when used right that sound can be very emotional. So I tried to kind of leverage all of those things together and take it one notch off of what makes sense.