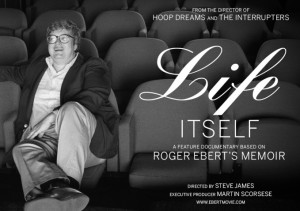

Interview: Director Steve James on the Roger Ebert Documentary “Life Itself”

Posted on July 5, 2014 at 3:32 pm

Roger Ebert said that Steve James’ documentary “Hoop Dreams” was the greatest film of the first decade of the 21st century. He wrote, “A film like “Hoop Dreams” is what the movies are for. It takes us, shakes us, and make us think in new ways about the world around us. It gives us the impression of having touched life itself.”

Those last two words became the title of Ebert’s autobiography. And when it came to make a documentary about Ebert’s life, James was the one Ebert wanted to make it. There were no restrictions or approvals from the subject. Ebert wanted his story told the way James thought best.

I spoke to James about making the film and the great loves of Ebert’s life.

Roger loved it when his friend Bill recited the last page of The Great Gatsby. Why was that so important to him?

I think Bill really nails it in the film so I’m just going to steal his thoughts on it. Number one it’s a great piece of writing and Roger loved novels. He probably loved novels as much as he loved movies.

In fact when he was younger, quite young he was one of those guys that had charted out his life. He was probably about 17 when he said, “OK, I’m going to be a newspaperman and then I’m going to be a political columnist then I’m going to move to New York to be a novelist.” He charted that out.

So literature meant the world to him and that passage meant a lot. But I think what Bill says in the movie is true. It’s that it was about a self-made man. Now in Gatsby’s case there was a lot of artifice there. It wasn’t with Roger but that notion that you can come from modest or nothing background and make something grand of yourself I think appealed to Roger as a small-town kid from Urbana who went on to the big city and sort of conquered the world in his own way but in an honest way. And then you know it’s about loss. I think Bill talks about in the movie about the loss of Roger’s father and death and the way in which death sort of haunted Roger. When he lost his father at that young age, it was not something he ever really got over according to Bill. Bill tells stories about other passages that he loved too that of course Bill committed to memory. He would quote something and then Roger would say, “Tell me again.” Or they would be at a dinner table and he would say, “Bill, give me the last page of Gatsby or this Yeats poem. And Bill is one of those guys that just commit a lot of great stuff to memory including a great editorial passage from when Roger was in college that is just remarkable.

He was a fully formed writer at the beginning as Bill says.

Yeah. I mean if I was a writer I would have hated this guy. I mean really hated them, just hated him. He wrote so well, plainly but with spiritedness and well chosen adjectives.

How did you find someone to do the narration who sounded so exactly like Roger?

Really I owe this to Chaz and her team. They were looking for someone to come in and read some of his great reviews, audio recordings. We had been for editing purposes using the book narrator. He did a perfectly good job but he didn’t sound anything like Roger. So we had been using him in editing because it’s convenient, but I knew I wanted to replace him and my thinking up until they found Stephen Stanton was that we would just find someone who kind of sounded like Roger but we weren’t going to try to channel the actual Roger. But then when she said, “We found this guy, you should hear him,” I was just like, “Oh my God!” And then my next concern though was, he was doing like a review on the show so it was kind of swashbuckling Roger and all that, it was kind of big and broad. So then I had him I reach out to him and had him read some of our narration passages that we had chosen that are much more intimate and he said, “Okay, I’ll do it but send me whatever kind of intimate recording.” So I sent him Roger’s Fresh Air interview with Terry Gross and we just sent him another interview that was done in Champaign with him where he was very relaxed and kind of speaking more quietly, more conversationally. He is not an impressionist; impressionist does not do him justice. He is an actor who can act in other people’s voices. He read the memoir himself before we did at the recordings. He listened to these tapes religiously and then he came in and he took directions like, I would say, “Oh, that was great but I feel like it could be even a little more private like we are just across the table together and you are speaking” and then he would boom! He was remarkable! He is so good that even though in the movie, in his voice, in doing Roger’s voice, he said, “When I lost my ability to speak…” there are a lot of smart people who say, “How did you get Roger to record it?” That irony of, “No way, that can’t be him,” just doesn’t even dawn on some people because they are just so immersed and that is what I wanted it to be. I did not want to fool you which is why I made sure you know if you are listening closely enough but on the other hand I want you to immediately forget it because it’s Roger’s words.

How do you as a filmmaker bring together several very distinct episodes in his life?

You could call it a three act, four act, or even five act life. He had a lot of adventures and he went to a lot of places in his life. He left a small town, he went to Chicago and became a newspaper man and fell into this job reviewing movies and then there was drinking and then he gave that up. Then there’s the TV show and then Gene’s dying and then the cancer and then the blogging. I mean it’s like there are so many aspects to Roger’s life. Plus he loved to go to the Cannes film Festival and he loved to go to the Conference on World Affairs and a lot more.

I felt like I wanted to use the present as a springboard to the past, something he does in a memoir in places which was really moving to me and so I wanted to do that. But otherwise when I do interviews, I do interviews with people for hours on end and we talked about a lot of stuff and not all that got in the movie but when you start to put the movie together, you start trying to identify what are the strongest strains in his life and I guess what I kind of came to realize is, and I did not realize this from the start but I came to realize that the film is kind of ultimately a series of love affairs. It’s a love affair with writing, it’s a love affair with movies, it’s a love affair even with Chicago of course. And then there’s Chaz.

And kind of like what all those love affairs add up to, in a weird way it is a love affair with Gene Siskel. It’s a torturous one but it’s a love affair. It’s like he had a series of love affairs but he was never not true to his wife. It all adds up to this kind of love affair with life. I mean he called the book Life Itself, not My Life and Movies or Me at the Movies. “Movie” is not in the title. It’s life itself that was the grand movie of his life, you know what I mean?

Was it hard for you to maintain objectivity as Roger became seriously ill?

I never worry about trying to maintain objectivity in that kind of journalistic way. Because like for instance I knew that this ultimately was going to be an admiring portrait of Roger Ebert because I wouldn’t have wanted to make it otherwise. I am not that kind of filmmaker. I want to be around people I am interested in. And so I knew that so it was never going to be objective in any kind of purely journalistic way. I did not go out of my way to find someone who hated Roger or something. But I went out of my way to find people critical of his contributions. I knew that I wanted it to be honest, though, and I think there is a difference between honest and objective. Honest is it may have a point of view and I feel like all my films do but I try not to make my point of view blow out of the water and eliminate anything that’s contrary to it, that’s contrary to who this person is or that there is other ways to look at this person. And so that was important. I mean when I saw how stubborn Roger could be with Chaz, I was a little surprised until I thought about it, “Well, you don’t get to be Roger Ebert and you don’t survive all he’s been through without being stubborn.” And I am not talking about just doing this; I’m talking about 20 years with Gene Siskel. You don’t get to be that way without having a stubborn streak in you. He had had a toughness about him that was essential to his success. He also had a generosity about him that everyone commented on that didn’t just happen late in life. Although he became even more generous, it was there all along.

In the film we hear filmmakers talk about how instrumental he was in helping them. How did he help you with “Hoop Dreams?”

First, he and Gene reviewed the film on the show when it was just going to Sundance. For them to even review it was remarkable because it had no distribution and it was three hours long and they knew that. And so they watched it and then they decided they were going to go on the show while it was at Sundance and they said something to the effect of, “You can only see this film if you are at the Sundance film Festival but we really feel that this film should be seen by a wider audience.” And they just sort of planted this flag. Sundance made an enormous difference because up until then, it was the three-hour documentary about two kids playing basketball that no one ever heard of and nobody was really going to see it. It was getting some buzz with the audiences a little bit but the distributors weren’t. And then suddenly, it was like we were a hot ticket at Sundance and we had ended up with three or four different offers and none of that would have happened without what they did, no way that would’ve happened even if they loved it.

And then over the years, Roger continued to write very thoughtfully about my work and support my work. Three years ago when “The Interrupters” came out, when it premiered at Sundance, we had sent a screener to him, just hoping that he would watch it. I don’t tweet but someone told me, “Roger just tweeted this wonderful thing about the film at Sundance.” He knew that we were premiering there; he knew exactly what he was doing. He had 800,000 Twitter followers; it was picked up, it was tweeted all around and then he continued to champion that film right up through the end of the year and was outraged when we did not get shortlisted for the Oscar. He was just such a supporter of my work. For me to be able to kind of do this film means a lot.