Interview: David France of “How to Survive a Plague”

Posted on July 7, 2012 at 8:00 am

“This isn’t a movie about what AIDS did to us,” writer/director David France told me as he was preparing to present “How to Survive a Plague,” his documentary about AIDS activism at the prestigious Silverdocs film festival in Silver Spring, Maryland. “This is a movie about what we did to AIDS.”

France made the film because most of the cultural touchstones associated with AIDS like the award-winning plays “The Normal Heart” and “Angels in America” and the book and movie “And the Band Played On” document the early years. They are filled with images of emaciated victims, weeping friends and family and bleak prospects. But this is a story of inspiration and triumph, as one of the most devastating diseases in modern history went from being a certain death sentence to an illness that can be managed. More than that, the people in this movie changed the way the medical and research communities interact with patients and their families who are coping with all diseases and conditions.

The film recognizes that the activists who led the fight in what became one of the most successful public initiatives in American history deserve recognition for their extraordinary accomplishment. In less than 15 years they were able to transform the medical options for people with HIV and AIDS and the ways that all medicines and treatment are developed. Along the way, they established the foundation for full integration of gay members of American society, with the freedom to be themselves and love the people they love. I spoke to director David France about the unique opportunity he had to make use of the extraordinary archive of footage used to document the movement from its earliest moments. This is not just the story of a brave and dedicated group of activists literally fighting for their lives. It is the story of how a heroic and remarkably effective political movement came of age, with its internal conflicts as well as the external ones. And it is the first time any movement has had the benefit of this range and depth of documentation, an explicit commitment going back to the earliest days.

“I didn’t want to over-burnish the halos of these guys, although I do think of them as heroic. But heroism is never a direct line; it is not a single path leading you straight to victory. And as in all movements, there are sharp differences and especially over time. ‘How to Survive a Plague’ covers nine years and four Presidents and in that period we see a lot of accomplishment and a lot of failure, as with any movement. The failures, despite the accomplishments, meant people kept dying. And people who were in the trenches, comrades of people I was following, didn’t make it. The desperation that underlay turned inward, as one might expect and ultimately created real battle lines among the activists. Those I thought were essential to tell, not just because they’re true, but because that’s human nature—and the fact that they were able to accomplish what they accomplished despite that was phenomenal. That made their triumphs even more unusual, that they worked through that anger and despair and self-doubt, suspicions among one another and still found a way to their end, and their end was the development of a drug that would finally make survival possible.”

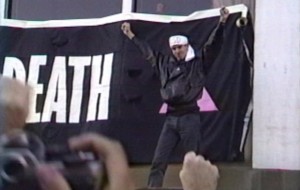

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQbM4bb6ZpkWhat makes the film so remarkable is its use of the extraordinary archive of footage. In all the political movements that have been recorded over the years, this one was probably the most thoroughly documented. France explained, “It’s the first kind of self-documented movement. HIV was first identified in the medical literature in 1981, the summer of 1981, and the camcorder hit the stores for the first time in the summer of 1982. So, in a way, they’re like siblings—sibling epidemics, really. They grew up together and became pandemic, right? So people involved in AIDS saw the value of the tool at a time when no one was covering AIDS. AIDS suffering was not being paid attention to. AIDS activism was ignored and the only images that we saw through the 80’s and really through the 90’s about AIDS were skeletonized patients in bed. We saw them on the news from time-to-time. We saw victims, and the people who were doing AIDS activism and knew that that was only a small fraction of the story and that the story of what was going on was really about self-empowerment and that it was brilliant, and that it was new. There was never a patient population that had identified and developed the kind of strength that this group had, and in order to be able to capture that and reflect it back to the individuals, they’d use these tools—and they started shooting everything. By 1987 when AIDS activism took full force, cameras were everywhere. From the very beginning of Act Up, they had a committee called DIVA TV, Damned Interfering Video Activists, that’s what they called themselves, DIVA, and they created TV. It was also the beginning of cable, of public access—they grabbed a public access station—and every week they would, on their public access shows, show the footage of what happened last week in a way to build the movement and to reflect back to the people who were doing it, the beauty, really, of what they were doing and to show AIDS power, to show fierceness, to show agency in AIDS at a time when that was being denied. That footage was—my thought was from the beginning that there was enough of that, because I saw those cameras—there was enough of that footage that I could create a documentary that would bring us back to that time. I brought in, ultimately, footage from thirty-three different individuals. It was shot by activists; it was shot by video artists who would come through like the Guggenheim program, by film-makers who are now well-known, and by loved ones who just wanted to capture what the people they love looked like in their youth, knowing that that’s all they were ever going to have.”

It is fascinating to see the way the movement adapted and extended the social justice tools of the feminist, anti-war, and civil rights movements. “It used strict theater, it used teach-ins, it used the idea of ‘zaps’ which came from the anti-war movement in Vietnam, but they brought something else to it: they brought a strategy that they ultimately called ‘the inside, outside strategy.’ That’s what the film is about although we don’t call it that by name. They started as street guerrillas, and we see it in the early part of the film, in opposition to what was going on in the culture at large, in science, in pharma, in medicine, in government—and after a year or more of just being out on the street saying ‘stop what you’re doing and give us drugs,’ they realized that that wasn’t enough, that they had to start refining their demands. They couldn’t just be in opposition, they had to say ‘what we want instead…’ and in order to do that, they had to figure out what they wanted. They began a really pointed course of study in immunology, cellular biology, pharmaceutical chemistry, and they taught themselves. At first, they thought they had to teach themselves the language so that they could, in their confrontations with people whom they hoped would find a drug that would save their lives, they could speak with them in their own language. And then that turned out not to be enough. They needed to be able to engage those people in ideas, and that’s the development of that inside strategy. Ultimately they became as well-versed in the aspects of drug-development for their disease as anybody. They sat at the table with Nobel-prize winners and directed the kinds of research that those kind of Nobel Prize winners were conducting, and they were grateful for it, they were grateful for the help and the direction.”

It is fascinating to see the way the movement adapted and extended the social justice tools of the feminist, anti-war, and civil rights movements. “It used strict theater, it used teach-ins, it used the idea of ‘zaps’ which came from the anti-war movement in Vietnam, but they brought something else to it: they brought a strategy that they ultimately called ‘the inside, outside strategy.’ That’s what the film is about although we don’t call it that by name. They started as street guerrillas, and we see it in the early part of the film, in opposition to what was going on in the culture at large, in science, in pharma, in medicine, in government—and after a year or more of just being out on the street saying ‘stop what you’re doing and give us drugs,’ they realized that that wasn’t enough, that they had to start refining their demands. They couldn’t just be in opposition, they had to say ‘what we want instead…’ and in order to do that, they had to figure out what they wanted. They began a really pointed course of study in immunology, cellular biology, pharmaceutical chemistry, and they taught themselves. At first, they thought they had to teach themselves the language so that they could, in their confrontations with people whom they hoped would find a drug that would save their lives, they could speak with them in their own language. And then that turned out not to be enough. They needed to be able to engage those people in ideas, and that’s the development of that inside strategy. Ultimately they became as well-versed in the aspects of drug-development for their disease as anybody. They sat at the table with Nobel-prize winners and directed the kinds of research that those kind of Nobel Prize winners were conducting, and they were grateful for it, they were grateful for the help and the direction.”

One of the most touching moments in the movie is when a scientist says “How could I give up, when they don’t give up?” “They earned that place at the table not just by command of the language but by this army outside. The outside people were always there. If the inside people hit a wall—when they started going to meetings, those were closed-door meetings; they were bursting through those doors—and with the army outside, with thousands of people demonstrating in the streets. Ultimately, they were invited in. Ultimately, people started to understand that not only was there a moral reason to have them inside those doors, but there was a practical and scientific reason to have patients and their advocates sitting at a table. And that is now across the board. Every disease, every pharmaceutical company, every government drug trial, all have community people sitting there participating, not just on the side of the table where the drugs are approved, but the other side of the table where drugs are being identified and studied and discovered. Everything in healthcare today is a product of that. Everything, from the way that patients and doctors interact—before AIDS, that was a linear expert speaking to a patient/victim. That was no longer allowable and now is the norm, that we are individuals who are discussing this with one another and plotting this out together the way drugs are identified.

“Crixoman is the first drug that comes to market as a product of what they call ‘rational drug design,’ a brand new idea about how to design a drug, which is to no longer just take things off a shelf and pour them into test-tubes and see what happens, but to actually look at the problem and decide what the solution to the problem is, in this case, to block that little enzyme called “protease,” find out what that enzyme looks like, design, architect a molecule to fit into that to stop it from doing what it’s doing—was never done before. It’s the dawn of modern drug research, the way drug research is financed, the way drugs are looked at by the FDA for approval and regulation. They helped devise this idea of surrogate markers, which are used now in all research. A surrogate marker being the thing that we know is indicating that the drug is less effective in this population than that population, without requiring people to go blind, without requiring people to get pneumonia and risk death. So, surrogate markers now, they had to be proven to be effective and now in most drug research, that’s the way they’re doing those trials. All of that is a creation of AIDS and AIDS activism, but literally scripted by the guys in this film. It’s amazing.”

France told me that his goal is to have the story of AIDS activism adopted as a part of America’s legacy the way that the civil rights struggle is. He was inspired and influenced by the classic “Eyes on the Prize.” And he remains focused on what still needs to be done. “Six million people are on these drugs that we see being developed in the film, and their lives were saved. But there are 28 million more people who need the drugs and have no access to them because they live in places where they can’t afford them, in a world that doesn’t have the political will to get those drugs out to them, and it’s not that expensive. It’s $100, $150 a year to bring those drugs to individuals in the third world who need them. It’s down from $10,000 for the first set of drugs, but why aren’t we doing that? Until there’s a cure, we’ve got to make sure that the breakthrough that happened 15 years ago now is available to everybody, and that’s what I want people to focus on: how to make sure we keep these people alive long enough for the net breakthrough in science to come and be available to them.

“Congress has passed legislation that’s still in effect that provides federal money for people with AIDS to get medication. It’s called the AIDS Drug Assistance Program, ADAP. No other disease has that umbrella of protection. The money is delivered to states and the states dole it out…and it’s not enough. There are, today, 2,300 people on waiting lists for drugs on the ADAP program, but that’s still a drop in the bucket. So, people with AIDS are getting this in this country (for the most part.) It’s really foreign policy, foreign public health policy that needs to be challenged. George W. Bush, for all of his failures as a president, he accepted, at the behest of one of his gay staffers, that it was in the U.S. interest to keep people alive in Sub-Saharan Africa, who have HIV. He committed billions of dollars to getting drugs out, and that program called PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief, is the single-most revolutionary part of American foreign drug policy, and Obama’s rolled it back. He’s rolled it back in favor of another program through the World Health Organization that’s not as effective, and the numbers are going to go down. We have six million people now on drugs around the world, and that number is going to start shrinking, even though he’s announced he wants to bring it up to 8 million, and Hillary Clinton has announced that she wants to create an AIDS-free generation, as a result of U.S foreign policy. It’s not going to happen without the money. We need the money to do it. It’s possible. You know, there’s something else. These drugs –completely unexpected side benefit of these drugs is that effective treatment on the protease inhibitors-based drug regimen render people with HIV nearly non-infectious, so they’re also prevention. So, if we can get people on these drugs around the world, we can effectively end the pandemic.”

2 Replies to “Interview: David France of “How to Survive a Plague””

Comments are closed.