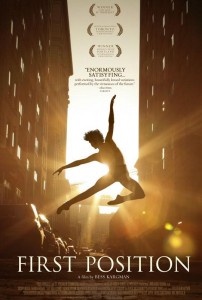

Interview: Director Bess Kargman of the Ballet Documentary “First Position”

Posted on May 17, 2012 at 8:00 am

First-time filmmaker Bess Kargman brought her own experiences studying dance to her documentary, First Position, about a crucial, career-defining competition for young ballet artists. The Youth America Grand Prix was launched in 1999 by two former dancers of the world-renowned Bolshoi Ballet, Larissa and Gennadi Saveliev. Its mission is to provide extraordinary educational and professional opportunities to young dancers, acting as a stepping stone to a professional dance career. I spoke to Kargman about how she selected the students she followed through the competition and why classical ballet is still a vital element of the performing arts.

You must be very excited about how well your film has been received.

I am! It’s very exciting, and I never expected anything, so it’s very thrilling.

Tell me how the project got started.

I danced my entire childhood, and this film was one that I always wished had existed. I don’t mean a dance competition film, because actually, I never competed growing up. Dance competitions didn’t appeal to me, and the Youth American Grand Prix wasn’t even around. What I mean is, a film that takes you far behind just the studio and the stage. I was so curious when I would watch dance films (especially dance documentaries) —what else? What do they eat? Whom do they live with? What are their relationships like with their friends? I just was very curious about more of the day-to-day or (some might call it mundane) activities in their lives that I thought maybe could count for a really full and interesting story. I ended up quitting my job to make this film, my first film, and I thought maybe by choosing a topic that was quite dear to me and that I had lived for a number of years growing up—maybe I’d be able to do this story justice.

Is it possible to be a dancer without a very supportive family? It seemed to me that these families were giving up as much as the girls and boys were.

I think in Europe and potentially other parts of the world, it’s possible to make it as a dancer with less support, but in America, where a 12-year old can’t drive him or herself to ballet class, a 12-year old can’t pay for point shoes, a 12-year old can’t pay for costumes, it really requires the whole-family’s buy-in. In Europe it’s more common to go to Ballet boarding school from a very, very young age and in that case the school takes on the burden of the costs.

How did you find the dancers that you focus on?

The story of how I found the first two dancers is sort of magical. A year before we began filming I was walking along the street in lower Manhattan and I saw huge banners for the American Grand Prix. It was the 2009 finals. I had heard about the competition but I really didn’t know all that much about it, so I snuck into the theater and got the last seat, high in the nosebleeds. If I had gone for a coffee I would’ve missed it—out on stage walked the most splendid, itty-bitty baby ballerina I had ever seen for someone so young. She was 11 at the time and I was just blown away by her strength and artistry and technique and maturity on stage. So I got up and walked out, and said, “This has to become my first film, I have to do this.”

I had no idea who it was, but I knew I wanted her to be in the film, and I recall that her name sounded half-Asian, so I went through the roster of 300 soloists that year, and the name Miko Fogerty popped up, and I said, “Oh my gosh, this has to be her.” And then her brother, Jules Jarvis Fogerty, his name was also under hers, and I said, “Oh, this is too good to be true. She has a brother?” So you know interesting things might happen when you have a sibling duo, so they were the first two people.

I then set out to sign a really diverse array of kids. When you’re making a competition film, if you try and predict the winners you’re risking the entire success of your film on factors you have no control over. I just couldn’t live with the idea of shooting for a year, shaping a film which no one would watch because it all came down to who would win—and I chose the wrong one. Instead, I chose kids whose personal stories and personalities and hobbies and families were so unique and interesting that I thought, even if the last five minutes don’t go so well at the competition, and no one takes anything home, that maybe the audience would still have a wonderful time if they fell in love with these dancers and learned who they are as human beings. That’s why the competition really only takes up a third of the film, I focused less on the competition and more on young dancers having a shared dream and being really diverse from all over the world, all different types of personalities and different age groups. Interestingly, when I was getting some advice from some very experienced film-makers they said I was really setting myself up in a bad way if I chose kids from all different age divisions, rather than from one age division. They said that if I didn’t have the kids fighting against each other on the dance floor, that it would lack a lot of drama—and I just thought to myself, well, the whole point is to show how the stakes differ depending upon age and to show how a dream differs depending upon your age or not. Maybe the 11 year olds want it just as badly as the 17 year olds, so I thought even if maybe there wasn’t that backstabbing and there weren’t kids giving each others terrible looks right before they’re about to go on stage because they’re not in the same age division, I was still willing to take that risk because I really did want to show more than just one age division. And what mattered was the individuals, not who they were competing with.

Why did you leave dance?

My advice to young dancers who want to make it as professionals is: Do not do it unless it is literally the only thing that you want to do with your life. It’s really difficult. It’s so demanding both in terms of your time and the way you have to use your body and it’s expensive. So, basically I came to the determination when I was thirteen and half and said, “I love other things just as much.” That signaled to me that maybe it wouldn’t be smart or healthy for me to focus on that exclusively. I became an athlete and I loved sports just as much, and then I wanted to go to high-school and play sports. So, I think what’s good about the age that I left dance was that I never lost that glorious appreciation for it. I think maybe if I had continued to stay in it and pushed myself, full knowing that I liked other things just as much, maybe I would’ve come to resent it or be bitter. I know that sometimes young dancers are hurt badly with ballet, because they’re pushing themselves, like every day is a struggle.

Where did you learn how to make films?

I never went to film school. I earned a graduate degree in journalism from Columbia and in my final semester there, I took a very influential, inspiring class with a substitute teacher named John Alpert who is a documentary film-maker for HBO, and he kind of challenged me to see if I could make a film myself. A couple of years passed before I was willing to take that risk, so I freelanced as a journalist and then I found a subject that I couldn’t not do. I always give advice to first-time film-makers and my advice to them is: you have to do for your first film a topic that is very personal, where you have some sort of area of expertise to compensate for the fact that you’re a first-time director—so I thought, “I know a couple of things, I know hockey and I know ballet,” and thought, “Let’s try ballet.”

How did you get your young performers to be comfortable enough to be honest with you?

One thing I learned very quickly is that dancers are used to expressing themselves with their bodies, not their mouths, so in the beginning they were exceptionally shy which is scary. At first, our cameraman said, “You’re going to have to recast this entire film because they’re not opening up to you.” We then decided to turn the cameras off and really bond with them and to get to know them. We worked to earn their trust. I don’t blame them, you know. If were expecting them to really open up their lives and share their stories, then we should allow them to get to know us as well. I got a skateboard for my cameraman so he could go skateboarding with them and we’d go point-shoe shopping and just do some fun stuff, and then they opened up in a big way, which was essential. I am fascinated by their stories and would love to come back and do a sequel in ten years: “Second Position.”

There are so many great movies about ballet. Do you have favorites?

The one that I watched over and over on repeat growing up, was The Children of Theatre Street – The Story of the Kirov Ballet School, the one that’s narrated by the princess. Forever engrained in my memory are the slow-motion shots of the dancers running, doing grand jetés on the beach. There are also all of the classic ones that I would find—in the days before YouTube. There is now an abundance of ballet content, but some of the things that I would watch on VHS tapes growing up were not translated, they were Russian documentaries—but it didn’t matter because you just absorbed the visuals.

You touch very lightly but candidly on the issue of ballet’s traditional approach of focusing on white dancers with long, thin, slender bodies.

It was important to me on that and other issues to let the people in the film speak for themselves. You never hear my voice, even asking questions. It is a complicated issue because ballet is grounded in traditions that include a very particular body shape and line. But dance has many varieties and opportunities and everyone who loves dance can find a place.

What do you think it is that makes classical ballet so enduring over hundreds of years in a world where people listen to hip-hop, and as you said, watch Youtube videos—why is it that we still go to a live theater to see dancers dance the same dances they’ve been doing for hundreds of years?

I think that there’s something about ballet which is magnetic. When you see people doing things with their bodies that are so disciplined and practiced, and requires so much of both TLC and training. I think that you don’t even have to know anything about ballet to know when you’re seeing something on stage that is incredible. I think that ballet’s focused on lines of the body. It’s just beautiful, it’s really beautiful, and I think that-everyone marvels when people can do things with their bodies that the average human being can’t do.

Can’t Wait to see this.

Congratulations on following your dream! We enjoyed your documentary so very much. My girl is a budding ballerina – she wants to go to Russia to train…..time for a little research. Thank you so much!