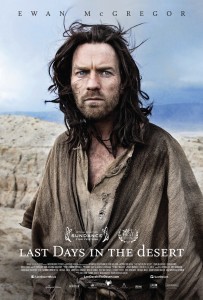

Interview: Director Rodrigo Garcia on “Last Days in the Desert”

Posted on May 11, 2016 at 3:14 pm

“Last Days in the Desert” is the story of Jesus in the final moment of his time of reflection before accepting his destiny as the Messiah. I spoke to director Rodrigo Garcia about creating the story of a critical moment that is not described in the New Testament and working with his international cast, the storyline about Jesus’ interactions with a family, and with three-time Oscar winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (“Gravity,” “The Revenant”).

How do you cast the role of Jesus, especially when you are going to have the same actor play the devil who tempts Him? In my opinion, the first requirement is kind eyes.

Well I think you know what I’m looking for because you’ve already said it. Ewan McGregor is a very good actor. I already knew that about him. I didn’t initially think of him because Ewan is in his early 40s and I was looking at men who are around 30, 31, 32. So I didn’t initially think of him but then I meet him socially and spent time with him and the kind eyes are there. Literally what Ewan has is a great human thing about him. He’s very likeable and he is very empathetic. You know he’s interested in other people. Her feels for other people. He is interested in human things. He doesn’t have a prejudiced bone in his body. He is just that person. That was very important to me. What I wanted was someone who has the kind eyes but also projected a real humanity, not a starry-eyed Jesus that seems of another world. Jesus is at least half human so I wanted him to feel like a person. I wasn’t going to deal with the divine side because how do you deal with that? How do you cast that? How do you play that? So we concentrated on the human side and his empathy and his kindness. It’s not without complication. Sometimes he says the wrong thing or might not make a good choice to intervene in the problems of the family. You could even argue that he helped but in helping he also hurt. He makes mistakes like humans make mistakes but he does have kind eyes and not just literally but as a metaphor. He sees the world and other with kindness.

You had a small cast, and each was from a different country, none of them from your home country. What does that international range bring to the production?

I think whether you’re working with actors from the same country or from different countries no two brains are the same. That’s the beauty about movies. When you work with other artists and things come together in a movie then they come together beautifully because it’s not just personality but also psyche comes together. Things people don’t know about themselves come out in the movie. Some people were religious and some people were less religious. A couple of people were Jews. It doesn’t matter. Everyone understood the theme of the movie. Everyone understood the movie was about fathers and sons and about the mysteries and about the incredible journey of Jesus. So when movie works it makes this infallible chemistry between those people of different origins come together, everyone’s conscious and unconscious is coming together around one idea.

What draws us to the desert, or the woods, or our own places of refuge and contemplation?

I think people of all faith and all religion and all spiritual philosophy go to the desert. You go to the desert, you go to the ocean. You go to where the noise stops and you can spend time with yourself and with the Universe, with the oneness. That’s what the desert is like. It’s both dangerous and ruthless but it’s also beautiful and you really get a sense of time. There are landscapes that probably haven’t changed that much in hundreds of years maybe thousands. So much of the movie was about men living in time. How we live and we move on. So, this movie was set at the end of something and at the beginning of something, it’s the last days in the desert for the mother and the father who stay and it’s the last days in the desert for the boy and for Jesus who go on to two very different destinies. The movie happens sort of at the first page of a book and at the last page of a book.

One of the things that I really like about your films is that you focus on those in-between moments not on the big climax or revelation but on the moments we may not understand until later.

A part of me is a minimalist. A lot of directors as they get more success they want to make that bigger movie on a bigger canvas with a bigger budget. I’m very Japanese that way. I’m always trying to see how can I do it simpler. I’m always fascinated by these Japanese artists that do calligraphy. They’ll work on a character forever, sometimes for life looking for that perfect stroke. I do like that. I like that minimalist thing and sometimes I have a lot of dialogue in films and I get a lot of praise for my dialogue but in the end all the important scenes in the movie have to be non-dialogue scenes. They have to be moments when people have to say good bye. Moments when people fall from cliffs or on crosses or just the silence, you know. I think sometimes in the movie the crucial moments cannot be dialogue moments. They have to be visual and silent moments.

In this film the characters talk about the most ordinary things in a very relatable way.

I wanted the conflicts to be simple but potent and they couldn’t be anything simpler than “I want my son to stay but my son wants to leave.” That’s a big conflict between a father and son wanting different things in life. That’s a conflict that is so relatable to any culture and any time and this looks small from the outside but for the people living in it, it’s brutal. It’s a really collision course and the mother is trying to intervene while facing death. Everything was as simple as could be. No matter when in human history, there will always be the issue: My father wants me to do this but I want to do something else. It’s certainly loaded because we know who Jesus is and what his destiny is. So anything that character does or says or doesn’t do or doesn’t say, we give it meaning because we know what awaits him.

Jesus and the boy are both struggling in that way.

My point of departure was Jesus was half human but that half is human. When you’re writing about a character you must think how is he like me, how am I like him. So the human half of Jesus must have confidence and insecurity, boldness and fear, fear of the unknown, a love for his father and of course some mystery about his father since his father was not someone you can just sit around with and talk things over. He probably had a sense of whatever the destiny was. He was probably going to make a grand gesture and maybe a big sacrifice. So the human man must have been, however committed he was, he just have been scared of what was ahead because who faces torture and death and crucifixion without fear. In fact if he had no fear the sacrifice would not have been the sacrifice that it was. I just dealt with the human side and the human side. I must assume is like me. Flaubert famously said, “Madam Bovary is me.” Well, that’s true of any character and I can only approach it if I am like him and he is like me and I think that’s what this one did.

What’s the best advice you ever got about being a director?

I was one doing a very emotionally loaded scene with Calista Flockhart. She walks into a room and find that her lover is dead. And right from the beginning she said we were going to do one take and I was already saying something to her and she said to me, “No, no I don’t want you in my head yet.” The lesson was don’t direct too soon. Let the actors, let your creative people, let the people you are working with come to the piece, bring themselves to the piece and along the way you are directing subtly but also hearing them out. You invite people and their subconscious to the piece. So I would say don’t direct too much too soon.