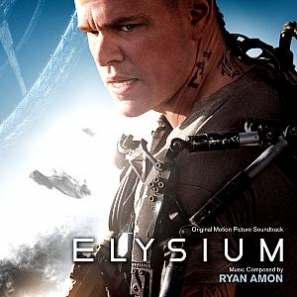

Interview: “Elysium” Composer Ryan Amon

Posted on August 5, 2013 at 8:00 am

Ryan Amon talked to me about the YouTube video that led to his first feature film score, in this week’s “Elysium,” directed by Neil Blomkamp (“District 9”) and starring Matt Damon and Jodie Foster and how two notes create a mood.

Ryan Amon talked to me about the YouTube video that led to his first feature film score, in this week’s “Elysium,” directed by Neil Blomkamp (“District 9”) and starring Matt Damon and Jodie Foster and how two notes create a mood.

How did you get involved with this project?

I had been doing trailers and before that I was an assistant on reality TV, so I had a lot of experience writing on deadline, but never anything like a film, which is a very different approach. I was living in Bolivia, where my wife’s family is, on a different continent when I got the email from Neill Blomkamp, who was in Vancouver. He had come across a YouTube video that a trailer music fan had posted. Someone had taken one of my tracks and posted it. Neill must have been searching through and found it somehow. And I got a one-line email: “Is this you?” I thought one of my friends was playing a prank on me. I’ve got very funny friends who have done things like that in the past. So I didn’t think too much about it until his assistant Victoria followed up, and I thought, “This is real.” Then I got nervous. He was still in the early stages but a few months later, he got in touch by Skype, with me still in Bolivia, and he talked about the film a little bit and his interests and my interests, and he offered me the job. You can’t turn that down! It was awesome.

When you have to write music for a story set in the future, how do you approach it? Do you try to project ahead to what kinds of instruments or genres will be used?

That’s tricky. I thought a lot about that one. His approach on this was not letting me see much of the film. I was working while they were filming. He didn’t want to let me read the script or see any footage. I had a few sketches of Matt Damon’s character in his exo-suit. So I had a few images but basically knew nothing of what was going on. My direction was to write something dark and then something light. It was a huge blank canvas for me. It was really hard but it was also very liberating and gave me a lot of room to experiment.

As for the future thing, who knows what music will sound like in 150 years? I knew I wanted to keep it relevant. Sometimes using too many synthetic elements, too many synthesizers, could backfire. In the 80’s, all those synthesizers sounded cutting edge and futuristic, but now they sound dated. So I wanted to steer away from that and bring in more orchestral elements. I took some traditional instruments, even piano strings, violin strings, and I scraped them metallically, and tried to create a sound that wouldn’t feel dated, even if we watch the film 20 or 30 years from now. We recorded in Abbey Road with the London Philarmonia. My first picture, and I’m in Abbey Road with a full orchestra!

Did you take a picture like the cover of the Abbey Road album?

Yes, we had to do that! It was freezing, in January, but it was still fun.

Before you were in Bolivia, where were you? What is your background in music?

I never really had that much interest in the classical side of things. I was classically trained and played piano and played the saxophone in a jazz band. But I was more interested in science, in biology. The music fell into my lap a little bit. I promised myself I would not try to do music professionally. But when I was in college I ended up enjoying coming back to my dorm room to play my guitar or I would write music on the piano instead of going to class. And I said, “Why am I enjoying this more, when it used to be such a struggle?” I think when you get older you are more comfortable embracing the areas where you have a gift, start to appreciate it more and want to explore it. I went to the McNally Smith College of Music in St. Paul to learn the technical things and got an associate degree. It was very new, more of a guitar school than anything back then. They only had a songwriting course at that time, so I studied film scores on my own, by ear, watching a ton of movies to see what worked and what didn’t. That’s what I was trying to train myself to do, to be more cerebral.

I entered a competition through BMI called the Pete Carpenter fellowship that allows one or two students every year to go out and shadow Mike Post in his studio in Los Angeles. He teaches us the way he approaches TV shows and we get to score a few scenes as practice. That was invaluable. And I knew that was what I wanted to do. I went back home, packed up everything I had in my car — and it all fit — and went to LA. I worked at IKEA and Virgin Records, and then through BMI I got a job as an assistant for a group that was doing reality TV. So that was a fast and steep learning curve. We had to produce at a very high level but also very, very quickly, two to three tracks a day for the show. It goes into a library and the editors get to place it where they want to. The most valuable thing was learning to use the software.

How do you begin to work on a movie score?

In writing a film score you have to be more of a psychologist than a musician. I approach it a bit differently. I sit at the keyboard and play intervals, just two notes at a time. These two notes, played on one instrument, what emotions does that evoke for me? I make a list of vocabulary words, as many as I could, of what these two notes felt like. I realized that a lot of music can be written from our background in music theory. But I felt it could be much open than that, a much wider spectrum of colors and instruments. So I always try to write from someplace deep inside, not to sound cheesy, but I try to write from my heart and not my head. In a way it’s cerebral, but I’m like channeling it. For dark and light it’s almost like not having an image in front of you can help sometimes. You can picture the whole world in your mind the way you do when you read a book. It’s fun to do that musically — what would light sound like? What would dark sound like?

So when you saw it with the footage, how did that go?

It was a little bit cringe-worthy to me. The original idea was that I would do some of the music first and they would use what I wrote as a temp score, and then we were going to manipulate it and see what’s working and what’s not. Sometimes Neill likes experimentation and wants you to go off and do your own thing, but sometimes he knows exactly what he is looking for and he will push you to search for it until it clicks. So there was a lot of music written for this film. I did over 200 tracks and they chose a handful. When I saw the temps with my music I thought, “Oo, that’s completely different than what I thought it would be — it looks different or the editing is slower or faster than I thought.” So that was terrifying at first, but as we went along I flew up to Vancouver to work with the post-production team for the last few months. It was definitely a surprise to see some of the matches between the music and the visuals.

What are some of the movies that inspire you?

My favorite movie was always “Jurassic Park.” That film score by John Williams is perfect and Spielberg is such a great story-teller. I love “Braveheart” and I would love to do a movie like that in the future, very raw and the power comes from traditional instruments. I love that old sound from the old world, what it might have sounded like in those days. I love hybrids, too. That’s a little bit of what I became known for when I was doing trailers.