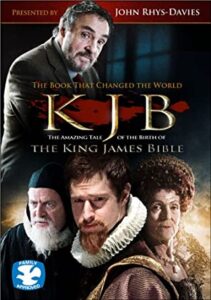

Interview: John Rhys-Davies of KJB: The Book That Changed the World

Posted on April 10, 2011 at 8:00 am

I couldn’t help it. When I picked up the phone to hear the voice of distinguished actor John Rhys-Davies, I had to enjoy a moment pretending I was talking to Sallah from “Raiders of the Lost Ark” or Gimli from “Lord of the Rings.” Rhys-Davies and his gorgeous speaking voice have appeared in everything from blockbusters to “Star Trek: Voyager” and “Spongebob Squarepants.” I very much enjoyed speaking to him about the new DVD release of KJB: The Book That Changed the World, a documentary celebrating the 400th anniversary of the most widely-used and influential English translation of the Christian Bible.

How do you think about faith and science?

I count myself a a rationalist and a skeptic with a very conscious awareness of my indebtedness to Western Christian civilization and I am a fairly passionate defender of it. My background is as a Welsh Protestant and I find myself championing all sorts of causes when I find them unfairly portrayed. I am a believer in the evolutionary process and yet I have sympathy for the friends of mine who are creationists. I don’t find the positions incompatible. That means I irritate both camps. How do you expect God to communicate to people — to speak about event horizons and milliseconds? It is better to say, “In the beginning….” There is no necessity for them to disagree. Dare I say it is a failure on the imaginations of both parts.

The issues of faith I keep coming back to. I am convinced logically that to say there is no God is the act of a fool. When you get back to fundamental questions — why should anything exist? A, I’m not sure what the answer is in terms of the science and B, I’m not sure that science can even ask that question. And it is sophistry to say that it is not a valid question. In the absence of an answer, reasoned speculation seems to be legitimate. Given the size of the earth and the number of possible universes that exist — I was told once it was 10 to the 500th power. The revised figure is 10 to the thousandth to the ten thousandth power, a scale so far beyond our comprehension that to make any assertions about it is simply fatuous.

Don’t you think that is exactly why the Bible presents its lessons in parable and metaphor? Because so much is beyond our comprehension?

I think that is a very legitimate observation. Aquinas got it right when he said, “God is that which nothing is greater.” But the size of that greatness is slowly revealing itself to us.

Were you on location for some of this film?

Only a few occasions like Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh, where the kings of Scotland were crowned, Westminster Abbey, Magdalen College and the Bodleian Library at Oxford, and the library of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Beautiful places. And one had the privilege of meeting ultra-smart minds, people who could understand complex matters and give a simple, clear answer. Not like me! I can’t give a soundbite for love or money.

What surprised you in learning about the history of this translation?

The human drama. And the real surprise for me was the enormous sense of emotion that I felt when I actually held it in my hand. I was moved to tears. It shocked me into realizing how deep the instinct of faith is still in me. I’m choking up at the recollection of it even now.

You know that argument the traditionalists have with the modernists about the translation: “Then I shall see him face to face but through a glass, darkly,” that wonderful Elizabethan expression. It always happens to be my favorite because I know exactly what it means. Imagine murky, dirty, Elizabethan London. Carts, horses, noise, excrement. People dumped chamber pots onto the street. The glass windows were not the clear glass we have now but rather like those sort of obscure, bubble-filled slightly opaque things that let some light in but you could not exactly see through, and that’s the image they found of the way we can look at God.

The scrupulousness of the scholarship, the care, the sense of importance of what they were doing, the need to get it right, and the extraordinary tensions between them. And as they worked together and refined things, slowly they began to respect each other’s talents and scholarship. And that strange mutation takes place when you realize that what you’re doing is not just an exercise but a mounting sense of excitement: “What we’re doing is really extraordinarily good.” I think by the end they knew what they were making was pure gold.

One Reply to “Interview: John Rhys-Davies of KJB: The Book That Changed the World”

Comments are closed.