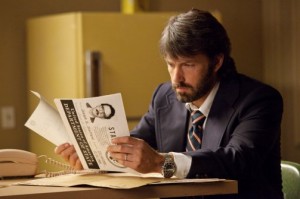

Ben Affleck directed “Argo,” the incredible story of a real-life 1980 CIA rescue mission, and he plays Tony Mendez, the “exfiltration” expert who came up with the idea to create a fake Hollywood film production company and get the six American out of Iran by convincing the people who had captured 52 other State Department employees that these six were members of a Canadian film crew, scouting locations for a big sci-fi/fantasy film. I spoke to him about the movie with a small group of journalists, the day after a screening attended by some of the real people rescued by Mendez.

You did something really remarkable in combining what is really two movies with two completely different tones in this film. How did you put that together so skillfully?

Well, I wish I could say it was my own skill, I don’t think it was. They’re really smart actors, they kind of looked at the material on the page and did me a favor of playing it honestly. Because it was played realistically it kind of blended anyway. If it hadn’t, I suppose I would’ve had a bunch of conversations about how we were going to get the jigsaw puzzles to fit, but all the parties, Bryan Cranston, John Goodman, and Alan Arkin were really pretty adept. They knew how to play it real, and that kind of saved my bacon.

Did you anticipate that there would be so much connection to current events and what do you think the movie can say about where we are now?

I was kind of stunned, naturally, just to see that the material that I looked at for research from 30 plus years ago all of a sudden was looking exactly like what was on the evening news. That surprised me and it surprised everybody and obviously, it was just a terrible thing for everyone. I expected the movie to be resonant to the sense of what happens when the United States gets involved with the government of another country and overlooks some of the negative things they may be doing because they’re pro-Western, the unintended consequences of revolution, those are the kinds of things I was anticipating. What it ended up being more about, in some ways, was an homage to our clandestine service and our foreign service folks, who, as illustrated by these tragic events do a lot, sacrifice a lot, put themselves in harm’s way, give up a lot to go overseas. Our Foreign Service folks are doing a lot and making a lot of sacrifices for us, and sometimes it’s even the ultimate sacrifice.

It really seems like you shot it as if it was a film made in the 70s, starting from the old Warner Bros. logo.

I thought it would be a trick of the brain, where, if you’re looking at a movie that looks like the kind of movie that was made in the 1970’s, it’s easier for the brain to subconsciously accept this notion that the events they’re watching are taking place during that period. Now, you can’t do that if you’re doing a movie about the Revolutionary War, but that’s why we had this interesting advantage. Even better, that era that I was trying to replicate, to sort of fool the brain, was a really great era for film-making, so I got to copy these great films and great film-makers, Lumet, Pakula, Scorsese.

How does it complicate things when you’re making what is basically a living history film, knowing that the people who were really there will see it?

It’s about a whole story, you know, and you have to maintain the integrity and the honesty of the spine of the story. That’s one profound responsibility because. I want them to look at it and say, “Yeah, that’s basically it.” Now, the real takeover was four hours long, and we have five minutes. That’s the kind of thing that we need to do to sort of compromise. It was raining in the real takeover, it’s not raining there. There are some details that are naturally changed. But the essential spirit of it, that has to be preserved. You know somebody did find a picture of Khomeini with the darts in it and say, “Who did this?” They really did blindfold people and things like that. I also have a responsibility to make a good movie, to tell a good story, because that’s what I do, and so those two things are constantly intentioned with one another, because I want to make it true, but I gotta make it good, you know?

How much was changed for dramatic purposes?

The main change, really, is the cars in the runway. They got to the third checkpoint, they got through, that was all the same, and they got there and sat there and they said, “Well, your plane has been delayed.” I thought, “Well, we’ve all been through that!” And then they got on the plane and left, and so in an effort to sort of externalize that and make the third act work, I added the sort of, them just barely getting away, when in fact they got away a little bit more ahead of the wire. But that really, fundamentally, in my view, doesn’t change the story. The same things happened, you know? It was a close-call in terms of trying to get out in terms of their own deadline. Most of the sins, really, in terms of story-telling, are sins of omission, you know? Not being able to include the fact that Pat Taylor got money from her co-workers or that in Ottawa they approved this special session to make these passports that had never been done before. You have people who are all alive, there’s a natural tendency to feel like, “Well, this is my story.” So you have to sort of do everyone’s story justice, and also take into account the sort of Rashomon phenomenon where you hear slightly different accounts from different people, and definitely maintain the realism of it while not sacrificing what’s really interesting about it.

What movies of the period ended up inspiring elements of this film?

There were a lot of them that I had seen and I still watched again, and I liked “The Thing” for my hair, and I liked Killing of a Chinese Bookie , the Cassavetes movie, for the sort of seedy LA, I just loved the look, the feel, the way they use zooms, the way it felt kind of raw but you also realized it was choreographed—and I didn’t expect to see that coming. There’s a movie called Let Me In

, the Cassavetes movie, for the sort of seedy LA, I just loved the look, the feel, the way they use zooms, the way it felt kind of raw but you also realized it was choreographed—and I didn’t expect to see that coming. There’s a movie called Let Me In that I watched, that’s really good, a guy named Matt Reeves directed it, the remake of the original one, and I thought it was really well directed and watched it with my DP, and we were looking at stuff that they did with focus in that movie, you know, keeping things in the foreground, focus, and maybe soft the background—that was something that I didn’t expect to influence me and it really did.

that I watched, that’s really good, a guy named Matt Reeves directed it, the remake of the original one, and I thought it was really well directed and watched it with my DP, and we were looking at stuff that they did with focus in that movie, you know, keeping things in the foreground, focus, and maybe soft the background—that was something that I didn’t expect to influence me and it really did.

I live near the CIA, so I got a special kick out of seeing our local dry cleaner featured in a brief scene in “Argo.” The building and sign haven’t changed since the 70’s, so it was a perfect touch of authenticity. It may look unprepossessing, but they note on their website that they do cleaning for “The White House, the Observatory (the Vice President’s House), Ford’s Theater, Blair House, the Kennedy Center, the CIA, the Department of Justice, and USA Today.” I asked director Ben Affleck about putting them in the movie. He said:

I live near the CIA, so I got a special kick out of seeing our local dry cleaner featured in a brief scene in “Argo.” The building and sign haven’t changed since the 70’s, so it was a perfect touch of authenticity. It may look unprepossessing, but they note on their website that they do cleaning for “The White House, the Observatory (the Vice President’s House), Ford’s Theater, Blair House, the Kennedy Center, the CIA, the Department of Justice, and USA Today.” I asked director Ben Affleck about putting them in the movie. He said: