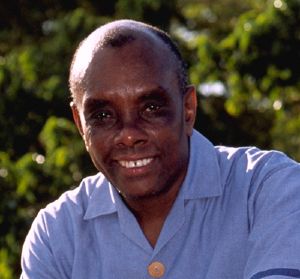

Interview: Father Joseph of Haiti on His New Documentary

Posted on October 5, 2016 at 3:46 pm

“Father Joseph” is an inspiring new documentary from Floating World Pictures about a priest in Haiti who has helped Fondwa, one of the poorest communities in the world, to develop schools, a radio station, and a bank and to build homes to make micro-loans to support the local economy. Almost all of it was wiped out by the devastating earthquake of 2010. And so, he is starting all over again, working with the Raising Haiti Foundation.

I spoke with Father Joseph, and the documentary’s director, Jeff Kaufman, and producer, Marcia Ross.

Father Joseph, what’s the first thing you do when you wake up in the morning?

FJ: Oh, it’s to be with myself and to be with God. First I want to stay awake and to talk to myself and to talk to God to see what is His plan for the day. I do have mine but what is His? But that helps me to stay out of trouble. And then take my shower. If there is any breakfast, I’ll take it and then continue. My day starts sometime at 5:00 and finishes at 10 PM.

So much is needed. It can be overwhelming and frustrating. Where do you begin?

FJ: Okay, as you know I am religious, I belong to the Spiritans and also I am a priest, a Christian and a Haitian. The first thing for me is to proclaim the good news, the gospel values. I cannot do it by myself, I need a lot of people. People who have the skills and people who are the beneficiaries. My aim is really to put the political struggle of the people, to put it together with my prayers and with the liturgy. And also to help other people to help themselves in such a way that we can break the cycle of poverty, to break the cycle of economic dependence.

Like in Fondwa, the first thing I did was to help the people to get organized and to identify the problems in their own living environment and to see how best they can help themselves. The country has been independent since 1804 but if the people still cannot get access to water, to healthcare, to education, to some of the basic human needs, that means nobody cares. The one who has to care is themselves. To give them the confidence in themselves to get back their human dignity, to help them to realize that they are somebody, they have been created in God’s likeness. They can do greater things that people think they cannot do. That struck me when we are looking at Jesus’ approach to the leper is in the society at that time. A leper in Jesus’ society was not sick but he was rejected and he has to accept that he is nobody in the society. More than that, he has to ring a bell when you are very far from him to say “don’t get close to me because I am not good.” Not only you are poor, you’re sick, but you have been disregarded and people put in your mind that you are nobody. And for me that’s BS.

That’s why also for me when I’m in front of you or in front of somebody else I think first, “I am walking on a sacred soil because you have been created in God’s likeness. I can help you as much as you can help me.” That’s why also basing on the gospel values for me I cannot be the only one who was access to water in my community, I cannot be the only one who has access to healthcare, the only one who can feed my children, the only one will have access to education. That means your failure is my failure, the suffering of somebody is the suffering of humanity. When somebody is hungry, it’s the whole humanity which has been disregarded. Nobody should go hungry, nobody should go without water, without healthcare, without education. That’s why as believers, I said believers, because in my work I work with Muslims, I work with Jewish people, I work with Voodoo people, I work with all types of Protestants, we see even celebrate the eucharist together because the work that we are doing for the poor bring us together.

That’s why I think as believers we are called to heal whatever is broken in our society. We have to become healers, we have to become build ‘bridgers’ and we have to be a living good news, a living gospel, we have to become a eucharist, the broken bread for each other. For me, that’s why it’s a big challenge for me to continue to work with the poor, to realize that so many young people are hungry and when they shower me with problems, I can only listen to them and that bothers me a lot to see that I cannot help them. Like a lot of young people in Haiti want to go to school, they cannot. They finish with high school they want to go to university, the college they cannot. That’s why I think this movie will bring more attention on the people of goodwill here of big heart who can get involved with us. I think together we can really create a better world for all of God’s children. So this movie is a part of the work of making those services and opportunities available.

Father Joseph, how does your home inspire you?

FJ: For me there is a beauty of spirituality by living on the top of the mountains. When you read the Scriptures you see that Jesus goes most of the time on the top of the mountain to meet with his father. And for me to be at the top of the mountain, to look at the sunrise or the sunset or to watch the stars, for me it’s a magical experience.

Marcia, how did you get involved with this project?

MR: The first time I met Jeff he was about to leave on his first trip to Haiti to meet with father Joseph. He had met him here prior to our meeting and I was very taken with what he was telling me about father Joseph and the work. I’ve had a wonderful career, including 16 years at Disney and doing casting, but I was really looking to do some other things with my life things to sort of open up my life experience. One of the great things about casting — it was my opportunity to help other people achieve their own goals. As a casting director you see talent and you try to help them get into parts that can change their lives and I think that was really fulfilling. But after so many years of doing it I really wanted to find other work that was fulfilling in a new way. And when Jeff told me this story I just started wanting to get involved into doing it. Making documentaries you meet people very totally outside anybody I have ever met. You meet people like Father Joseph, who do a lot of selfless work, the only reward is purpose in life really, there is no financial reward, there is no fame, there is no a lot of things but that doesn’t stop him from wanting to make a difference in the world. His motivation is not for fame and fortune for himself or recognition for himself, his motivation is for making a difference in the lives of others and I think that’s a very important idea.

FJ: You know the fact is people who join me in this work not only they help me to transform the lives of others but their own lives.

Jeff, you seamlessly integrated archival footage with new material in the film. How did that happen?

JK: We started getting footage of father Joseph in 2011 and started shooting initially in 2012 and had a series of shoots but one of the things that was kind of amazing was, we wanted to have a sense of the modern history of Haiti and also the evolution father Joseph’s community Fondwa. We reached out to a lot of people and what are the odds but here is this guy who grew up in the mountains of Haiti far from anywhere and we were able to basically find 25 years of videos of him here and there and other places speaking and it was from six or seven different sources.

It was great to get the video but it also represented the magic of this film. All these people you’ve never known before, you reach out to them and they help you in the most amazing way and they become partners in the effort. And then later on one of our executive producers is now helping with the University of Fondwa another of our executive producers is now helping with Father Joseph’s Peasant organization and its a miraculous thing to see. That’s always the intent of the film was to be more than just a film.

What kind of a crew did you have for your own footage?

JK: The first time I came to Haiti I worked by myself. I had done this film about Ella Fitzgerald and jazz in the 1930s, and by necessity I had done the audio myself, not a good way to proceed. You can’t bring a traditional crew to Haiti, you can’t ask them to work that hard and you can’t ask them to put themselves through the risk but my son Daniel had come out of film school and he had worked on a couple of projects first doing audio, editing some pieces, and his talent level just kept rising and rising and rising. And after a lot internal debates, and some concerns about physical safety, I asked Daniel if he would like to be the the cinematographer. Daniel was immensely talented and so I did the field audio and Daniel was the cinematographer. It was an an amazing father-son experience and I think Daniel made a lifetime of connections for himself as well.

FJ: That fits what we are trying to accomplish. As a priest, I gather as many people as I can to help them to discover their inner self and define the meaning of their life and to give back as much as they get. For me this is what I have been able to accomplish on my own and I want to share it with others, to really share what you have and what you are with others. For me if anybody can accomplish that, that means you have accomplished your goal in life.

JK: One of the remarkable things about father Joseph — he’s the perfect example of not just faith but faith and action. Faith has a lot more meaning if you actually use it to do good. More than that, he is the most inclusive priest, not cavalierly but based on who people are. He is a very passionate Catholic priest who really believes in that faith but he also really sincerely believes that good people of other faiths all have their own path to heaven. I probably couldn’t embrace him if it wasn’t for that and I love that openness to other ways of life and other paths. Where it came from in this guy I don’t know but it’s really unusual.

FJ: I think we cannot put God in a box and say that my God is the better God. We have to let God be God and contemplate God wherever we are and in whatever we are doing. In Creole we used to say “del mon de mon.” After each fountain there is another fountain.