Dennis Lim on Movie Fight Scenes

Posted on July 30, 2008 at 9:48 pm

Anything Dennis Lim writes about movies reflects his exceptional knowledge and insight and is a pleasure to read. His latest piece is about the way fight scenes are staged in movies is terrific — and his insights are accompanied by the film clips that illustrate his points.  From a stunning fight between Charlton Heston and Gregory Peck in 1958’s “The Big Country” to “Died Hard,” “Raging Bull,” and “The Matrix,” Lim points out the how the way the fight is shot and edited can convey as wide a range of emotion, character, and plot as the dialogue.

From a stunning fight between Charlton Heston and Gregory Peck in 1958’s “The Big Country” to “Died Hard,” “Raging Bull,” and “The Matrix,” Lim points out the how the way the fight is shot and edited can convey as wide a range of emotion, character, and plot as the dialogue.

I really like his description of the way that styles in the editing fight scenes have changed over the decades, partly as a result of technology advances that made quicker cuts and shakier, more close-in cameras possible.

Walter Murch, the venerable film editor reflects on how effective cutting keeps audiences grounded as one shot, often imperceptibly, becomes another. The trick is to determine where the viewer’s attention is trained in a particular shot and to cut to a shot that contains a focal point in the same area of the frame. But there is at least one major exception to this rule: the fight scene. “You actually want an element of disorientation–that’s what makes it exciting,” Murch says of his approach to splicing together a fight. “So you put the focus of interest somewhere else, jarringly, and you cut at unexpected moments. You make a tossed salad of it, you abuse the audience’s attention.”

Attention abuse is certainly one way to describe the on-screen tumult that is by now a summer multiplex ritual and that increasingly suggests even more aggressive terms than Murch’s. (Try pureed instead of tossed.)

And what a great description of the influence of the Hong Kong films and of the period when two-men fights briefly were eclipsed by bigger bangs:

Yet ’90s action cinema is a wasteland when it comes to fight scenes. Most of these frat-metal spectaculars, obsessed with scale and volume, were too busy detonating asteroids and dropping fireballs on major metropolitan areas to bother with anything quite as puny as one-on-one combat.

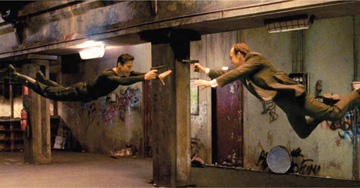

Until “The Matrix” came along, that is.

Here were fights (choreographed by martial-arts veteran Yuen Wo-ping) that defied time and space. CGI was not new, but The Matrix introduced the sense that anything is possible and, what’s more, could be conjured from nothing. The way you feel about most contemporary movies–and their fight scenes–probably depends on whether you find that prospect thrilling or alarming.

Fight scenes are the most powerful visual effect. In most movies that include them they are the climactic moment. One movie that reversed this was “Shoot ‘Em Up” a marvelous example of many fight scenes but only a little talking/exposition (Paul Giamatti’s character is even heard saying, “This guy is amazing!. I’m going to have to get more henchmen!”)

One year I was talking with a youth group about relationships and sex. The problem was they were more interested in wrestling on TV. So I tried an experiment with them. We outlined bioth a couple of soap operas and a couple of wrestling shows. What we dioscovered was they follow remarkably similar patterns – lots of talking followed by bouts of physical initmacy (making out / wrestling). So in some ways, the hyper visual fight scenes accomplish the same things as the smooching scenes in romantic movies. It is simply the nature of the visual stimulus that changes. This may explain the mixed interest in romantic fight movies (Crouching Tiger / Hidden Dragon is a great example).

Staging a fight scene is complex, storyboarded to extreme detail (as in comic books), carefully choreographed, well rehearsed, and if it is done well, excites the viewer. The same is true for good kissing scenes (From Here to Eternity) or even good sex scenes.