Interview: Matt Charman, Co-Screenwriter of “Bridge of Spies”

Posted on January 25, 2016 at 3:31 pm

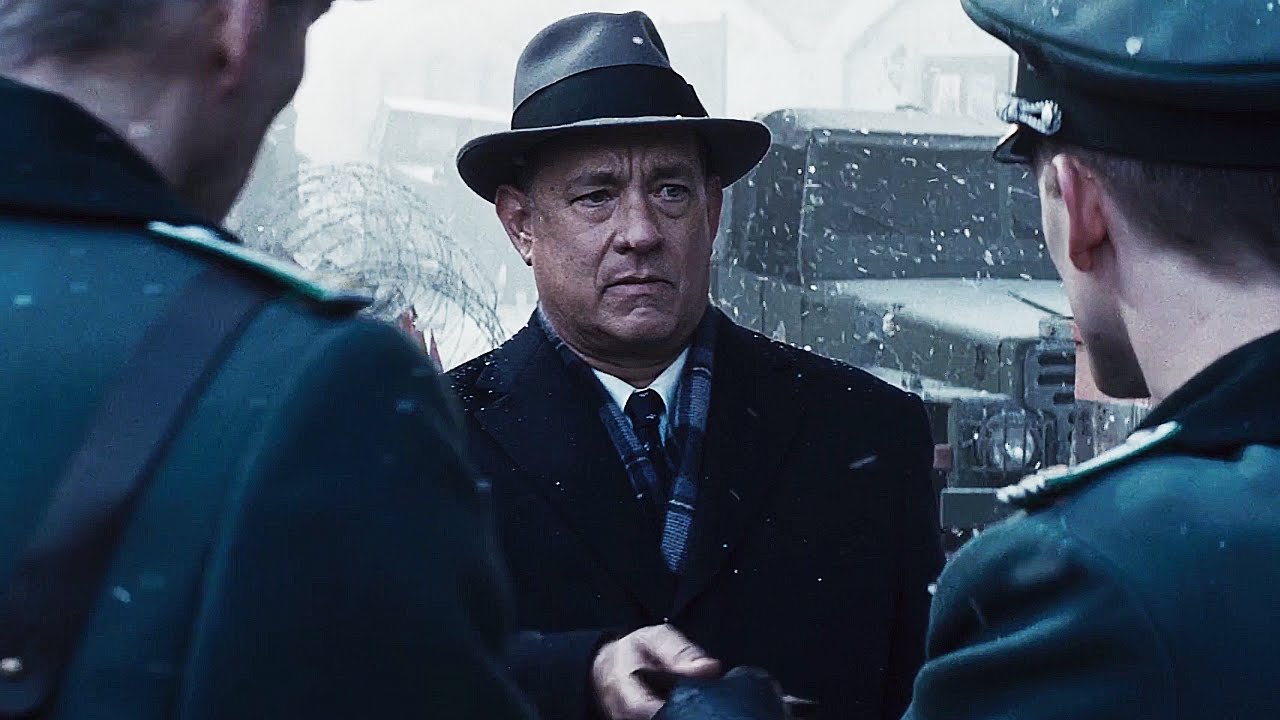

Matt Charman is a British playwright whose first script (with the Coen brothers) was for the Steven Spielberg movie, Bridge of Spies. It is based on the true story of an insurance lawyer named James Donovan (Tom Hanks), who negotiated a spy swap with then-communist East Germany in the tensest days of the Cold War. In an interview, Charman told me how he first discovered the story of Donovan, what he learned from Spielberg, and what he, as someone who is not an American, most admires about the US Constitution.

I had never heard the story of James Donovan.

I didn’t know all of that either Nell, I was reading a biography of JFK that Robert Dalleck wrote called An Unfinished Life and there is a chapter on Cuba. After the Bay of Pigs fiasco JFK sent somebody to negotiate with Fidel Castro for the release of the 1500 servicemen that had been caught and captured. And I was really amazed to learn that it wasn’t a CIA guy or anyone from the State Department; it was a lawyer. It was a New York lawyer, a guy named James Donovan. And in the footnote of the book it said “Donovan first came to prominence for the part he played in the spy swap with Gary Powers and Rudolf Abel.” That was it. The only mention in the book. And the hair on the back of my neck stood up. I couldn’t believe I never heard of this guy. It seemed to me that he had taken part in two really huge moments in history. The more I dug around the more I realized there really wasn’t any definitive account and there wasn’t anything out there that encapsulated the entire journey he was on. So I started to research the New York Times Archive and the Presidential Library and I went to meet with John Donovan, his son.

What I pieced together was what “Bridge of Spies” became, this remarkable untold story about a true American hero, a man who believed so strongly in due process and in the Constitution that he was willing to follow it all the way from a courthouse in Brooklyn to the Supreme Court through the Berlin wall in order to represent his client.

Your background is in writing plays. What did you have to learn how to do in telling a story cinematically?

There are huge differences. I grew up primarily with movies because I used to live in the middle of nowhere with my folks so I think I caught the bug for storytelling through largely watching American films. When I first came to London I started to have access to London theater and so I saw a lot of plays when I was studying in London. I mean it’s no surprise to me that Stephen Spielberg tends to work with a lot of playwrights who have become screenwriters, Tom Stoppard, Tony Kushner, who wrote the Abraham Lincoln film most recently. He gravitates towards writers who can build a scene, writers who can create a scene that have a start, a middle and an end, that have characters that want things, that make arguments, that believe strongly in certain values. They don’t have to be lawyers or presidents but these are people who stand for things. And I think my background playwriting meant that when I came to write this, this is my first original screenplay that I was really able to channel all the things that I knew about building characters to create this movie which is very much about a man arguing his case.

What did you find out about the British-born Soviet spy Abel, who is portrayed so brilliantly by Mark Rylance in the film?

His time in New York is sketchy. He was an enigma. He stayed undetected for 15 years operating as the top state of the art agent in America at the time. And one thing that I really, really sort of hung onto and was really impressed by was I read that he had a very bright sense of humor and I read that he had this very close relationship with Donovan, despite their different ideologies and their different backgrounds. There was something about both man that was very dutiful. Say what you like about Abel but he did his job, he executed his job in a way that was impressive and dedicated and it took him away from his family for a long time and yet he believed enough in what he was doing to kept going. And I think even though Donovan was completely at the other end of the political spectrum he admired the way in which Abel conducted himself throughout the trial. That blossomed into a friendship between them. So exploring Abel as an enigma but as somebody who slowly revealed himself through the movie was something that I was desperate to do. And really what was so exciting was when Steven said, “Listen, I’m going to call Mark Rylance.” I have known Mark Rylance from stage in London. But he hadn’t really done many movies, so suddenly an American audience particularly is seeing a man that they have no background for, they have no reference point, and they are seeing him slowly reveal himself to them through the course of the movie and I think that was genius in the casting from Stephen.

It’s always a challenge to introduce the main character to the audience in a way that is telling and gains our interest and loyalty, and as a lawyer I really enjoyed Donovan’s first scene, negotiating a settlement of an insurance claim.

The whole idea behind that scene really was to meet James Donovan as he was before he got this case which is in a way a challenge to an audience because he is an insurance lawyer. And furthermore he is an insurance lawyer who was trying to limit the liability of his client and therefore trying to deny claims against his clients. So I’ve always enjoyed the fun of that scene. You are expecting a Tom Hanks as Atticus Finch or whatever and what you meet is a guy in a bar or rather in this club who is kind of down and dirty negotiating and backing his client the full way. Steven always loved that scene because it’s such a playful way to meet Donovan. And then we take this guy from an insurance lawyer through this transformation into somebody who is really remembers his calling, and his service at Nuremberg, and he remembers all the good things that that meant to him and then hr ended up taking on this remarkable case. But it was fun to meet him in that way, I think.

Was it a challenge for you as somebody who did not grow up in America to tell such an American story?

I never saw that it as a challenge probably because I’ve always watched so many American movies and read so many American books, and also growing up being so influenced by Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams and all of those American playwrights. So no, to be honest with you it wasn’t. What I always knew I was doing was telling a story of a man, he had a family, he had wife, he had a job, he had the hallmarks of the kind of person I would live next door to in London. So he felt utterly grounded and utterly normal to me so it was the most natural thing in the world really.

The scene that seemed to me to be the essence of America is when he talks about people coming to this country from all over but having one thing in common: The Constitution. His affection — and yours — for the Constitution is very touching.

The Constitution of the United States is the most beautiful thing and I think it’s something that anybody can look at and appreciate, and hold up as being a set of values and a codified way of governing in a way as being so aspirational and so inspirational as well. I think anyone from any country can appreciate that, so I’m a huge fan of extolling its virtues.

So tell me a little bit about what you learned from working with Spielberg about filmmaking. What was the most important thing you learned?

I had this remarkable experience with Stephen which was a true collaboration and really where he was so pleasant, he was so open to dialogue and to talking things through, just trying things and being able to, not pressured at all which was wonderful because this is a man who has so much filmmaking experience you could imagine that he knows a certain way of doing things, and he would want to do it his way. He doesn’t at all and when you sit with him on set he is thriving on people’s ideas and their contributions that they’re making in that collaboration.

So what I learned from is two things really. First, he’s the most organized man I’ve ever met in terms of his preparation. He is like a military general. Second, he knows exactly what he wants to do and how he wants to do it but he has his remarkable ability to improvise. There was a moment when we were filming where suddenly he looked down on the floor and saw all these flashbulbs lying on the floor in the courthouse in the scene where they come out after the verdict. And he grabbed the camera and he got down on the floor with the camera himself. He said, “Okay, this here is what we want to do,” and he suddenly built the end of the scene where they walk out with the flashbulbs all over the floor. it’s a gorgeous moment with a bit of texture. He didn’t storyboard that, he didn’t plan for that but he saw the opportunity and he grabbed the camera and did it. So you have this man who is able to build complex sequences but also somebody was able just like a student filmmaker to adapt and adjust and improvise and for me that was kind of inspiring to see.