Interview: Phil Hall on “The Greatest Bad Movies of All Time”

Posted on August 7, 2013 at 3:59 pm

I always enjoy interviewing film expert Phil Hall, and it was a special treat to hear his thoughts about his new book, The Greatest Bad Movies of All Time.

The bad movies in your book fall into several different categories, including the big-budget train wreck and the well-intentioned but incompetent low-budget failure, the movies with aspirations of artistic greatness like “The Blue Bird” and the ones with none like “The Hottie and the Nottie.” Do you have favorite examples of each?

In creating the book, I wanted to offer the full depth and scope of the anti-classic experience. Thus, I brought together silent films that achieved profound awfulness without the benefit of spoken dialogue, documentaries that get their facts hopelessly screwed up, musicals that are weirdly off-key, biopics that turn the lives of their famous subjects into ludicrous travesties, comedies where the only laughs are unintentional, experimental films that self-destruct under their artistic pretensions, science-fiction that fails to capture the imagination, and one porno film that offers absolutely nothing that is even vaguely erotic.

I hesitate to offer personal favorite choices, because all 100 films represent my vision of how not to make movies. If anything, I wanted to affirm that cinematic incompetence comes in many shapes and sizes, from many countries and from many decades.

What makes the difference between a “so bad it’s good” hit like “Plan 9” or “The Room” that people enjoy watching or a movie that is too dull or painfully bad to sit through?

Most bad movies are just mediocre – they traffic in formulaic writing and adequate acting, and we forget about them shortly after the closing credits have rolled. But the anti-classics offer a genuine challenge to your intellect – you sit and watch them, wondering how anyone could have possibly brought forth something so wildly misguided without realizing the chaos they were creating.

In viewing these films, their awfulness becomes intoxicating – each reel brings a new assault on the senses. And by the time these films have run their course, the viewer is left in a state of shock and awe, and many people are immediately eager to share their experience with all of their friends and family members – usually by announcing, “You won’t believe what I saw!”

Which is more fatal to the quality of a film — a bad script, bad acting, or bad direction?

The screenplay is the foundation of a motion picture. If the foundation has significant cracks, then no amount of clever direction or energetic acting will help to overcome this significant handicap.

Of course, you can have a marvelous script, but it gets destroyed once the cameras start rolling. For example, the musical “Mame” has a delightful and charming screenplay, but putting the lethally miscast Lucille Ball in the title role threw the entire endeavor off-kilter.

Why are we so fascinated with failure?

I believe that people are fascinated with cinematic failure because it reminds us that the good folks in the movie business are no different from the rest of us. Movies are supposed to represent how life should be – but they create an idealized fantasy world where everyone is too clever and too good looking. Cary Grant – who, in real life, was absolutely nothing like his screen persona – famously commented on this by saying, “Everybody wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant!”

When films backfire on a grand scale, it provides a wake-up call that the big screen fantasy has nothing to do with reality. The gorgeous movie stars and the brilliant directors and writers are, ultimately, human – and they can make the same clumsy errors of judgment that anyone else can make.

What was the first bad movie you ever loved?

Forty years ago, I was an eight year old sitting in the audience of the UA Valentine in the Bronx, N.Y., during a presentation of the musical version of “Lost Horizon.” And I couldn’t help but enjoy a weird fascination with what was on the screen – it was a crazy and lumpy film, and it was certainly not the type of film that eight year olds appreciate, yet somehow it resonated with me. I can still remember the bafflement I experienced in the musical number when Bobby Van tap danced off a bridge and into a stream – and all of these years later, I still cannot believe that number was filmed.

You include some legendary flops and failures and some esoteric disasters that are just about unknown. What selections will be most surprising to readers?

I have already received some levels of surprise that Kevin Spacey’s “Beyond the Sea” and Clint Eastwood’s “Mystic River” were included, and a few people wondered why I put in a 2005 high school film version of “A Streetcar Named Desire” (which includes a dance number to “Pennsylvania Polka” – you can find it on YouTube). I’ve also received inquiries why certain turkeys were not included in the book.

I should note that the book is a reflection of my opinion, and it is not intended to be the last word on the subject. I try to explain why I feel these films can be considered anti-classics – and if I don’t change any minds, then at least I hope that I can earn some respect for stating my opinion.

Which of the movie failures has the most talented people behind it and what went wrong?

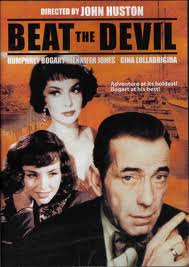

The problem with films that are created with all-star casts often make the mistake of believing that the performers’ charisma can compensate for problems in the screenplay and the direction. John Huston’s “Beat the Devil” and Orson Welles’ “Mr. Arkadin” have extraordinary casts, but both films had major problems with their screenplays – Huston’s work was written as the film was being shot and Welles was doing a lopsided riff on “Citizen Kane” – and the great directors were a bit more self-indulgent than usual with their respective works.

In many ways, I think that the saddest waste of talent of any of the 100 films was the 1954 offering “Dance Hall Racket.” That film had Lenny Bruce in his only film acting role – and he was cast as a gangster in a crime drama. Think about it: you take one of the most brilliantly funny artists of the 20th century and you cast him as a second-rate imitation of Lawrence Tierney. Why?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PoMniM9BwFEHow do bad films help us understand what makes movies good?

The great bad movies remind us that filmmaking is, ultimately, a magic show. When a film works, we don’t realize how the magic worked. When a film misfires, we see where the tricks went wrong – and we realize that the cinematic magic is a lot harder than we may have previously considered.