“Becoming Santa” — OWN Documentary

Posted on December 15, 2012 at 5:41 pm

The wonderful, poignant OWN documentary “Becoming Santa” is now available on DVD. I wrote about the movie when it was shown on OWN.

Posted on December 15, 2012 at 5:41 pm

The wonderful, poignant OWN documentary “Becoming Santa” is now available on DVD. I wrote about the movie when it was shown on OWN.

Posted on November 11, 2012 at 8:51 am

“Section 60: Arlington National Cemetery” is a documentary from HBO about “the saddest acre in America,” the final resting place of our military who made the ultimate sacrifice in Iraq and Afganistan. Emmy-winning producers Jon Alpert and Matthew O’Neill (Baghdad ER) capture the profound combination of loss, love and pride felt by cemetery visitors, portraying the losses sustained in military conflicts while honoring those who gave their lives for our country. The film shows the pain and grief of the families and friends who visit to pay tribute and find comfort and a sense of community. HBO has also listed resources for grieving families and those who want to help them.

Posted on October 12, 2012 at 8:00 am

Eugene Jarecki’s new documentary about the failure of the drug wars by any standard — economic, practical, moral — is a powerful and sobering call for treating drug abuse as a public health problem and not a criminal problem. I spoke to him about the film, his decision to include a very personal story, and what he has learned about programs that are more effective in addressing the problems caused by drugs.

You begin with a home movie about your own family and bring in a very personal story of drug abuse in a family close to you, unusual choices for a documentary about an important public policy issue. Why did you do that?

You ask yourself at a certain point when you’re making a film of this kind whether and how to be most honest about the role that you are playing as a pursuer of this information in these stories. Sometimes staying very much out of the way has its place, particularly in a movie like this where there are so many characters and there’s so much to tell. It seems like a clumsy vanity that I would be in the movie at all. I would have thought, “What business do I have being in this movie when the people who really need to occupy screen-time are the people whose the stories will appear in the film, who have so much to say about this broken system, whose lives are such a testament to its carnivorous behavior?” So what role do I have? And then at the end of the day, I played that game for a long time, but I was making a movie where it was very hard to understand what was the modus operandi of the filmmaker, because these stories were chosen in 20 or 25 states; they were all over the place at all levels of the war on drugs. When we would do early screenings for our friends and in the editing room it felt a little bit like there is a driving force in this film that is inside Eugene’s feelings about the country he lives in that is somehow missing here—and how do you inject a little bit of that without getting in the way at all? And so it meant the occasional glimpse of me as a pursuer of this national story, of trying to unravel this national mystery as well, was at least a role I could play. But to have me in there at all, of course, that brought up the fact that I had a deep, intimate, personal relationship with one of the stories I had been telling. In my early cuts in the film that early on, Nannie Jetter appears in this film just as a character, with no mention of the fact that I had an intimate reason for being interested in her. So that changed.

As a filmmaker, I’d like you to talk a little bit about the sometimes glamorous images that we see of the drug world in films, mostly fiction from feature films like “Scarface” and “American Gangster,” but also television shows.

Don’t lump “American Gangster” in with other movies that have been made about the drug war in America because American Gangster is already a post-modern take the drug war in that it is a movie that understands what my movie understands. It’s a movie made from a very critical perspective, where Steve Zaillian’s script really examines the war on drugs and the hypocrisy and the humanity of it all with a lot of wisdom, I was very impressed by “American Gangster,” particularly for a Hollywood movie. It’s hard to get good substance through Hollywood. Hollywood is a town driven by fear and by economics and the people in it, unfortunately whatever their inner politics are, they tend to make movies that portray images that are serviceable to some exploitative vision of industrialized film-making. So you end up seeing over and over dehumanization in the service of making a big box office, and the movies tend to exploit that in us which is our least and our worst rather than looking for that in us which is majestic and human. And so what I can do if I have my little camera and my little team and the idea of a movie, is to be an antidote to that, and to try and portray majesty in the human condition. That includes the majesty of a survivor like Nannie Jetter who survives slings and arrows I couldn’t imagine, or the majesty of a security chief in a prison who finds a way from his position of power to nonetheless risk his own job in talking to me and being so candid, to people up and down the chain of command who, in one way or another, demonstrate tremendous personal reserves. That’s the best antidote I can give to the dehumanized, cartoonish portraits that the industrial system produces.

Don’t lump “American Gangster” in with other movies that have been made about the drug war in America because American Gangster is already a post-modern take the drug war in that it is a movie that understands what my movie understands. It’s a movie made from a very critical perspective, where Steve Zaillian’s script really examines the war on drugs and the hypocrisy and the humanity of it all with a lot of wisdom, I was very impressed by “American Gangster,” particularly for a Hollywood movie. It’s hard to get good substance through Hollywood. Hollywood is a town driven by fear and by economics and the people in it, unfortunately whatever their inner politics are, they tend to make movies that portray images that are serviceable to some exploitative vision of industrialized film-making. So you end up seeing over and over dehumanization in the service of making a big box office, and the movies tend to exploit that in us which is our least and our worst rather than looking for that in us which is majestic and human. And so what I can do if I have my little camera and my little team and the idea of a movie, is to be an antidote to that, and to try and portray majesty in the human condition. That includes the majesty of a survivor like Nannie Jetter who survives slings and arrows I couldn’t imagine, or the majesty of a security chief in a prison who finds a way from his position of power to nonetheless risk his own job in talking to me and being so candid, to people up and down the chain of command who, in one way or another, demonstrate tremendous personal reserves. That’s the best antidote I can give to the dehumanized, cartoonish portraits that the industrial system produces.

You’re quite right about the conclusion of “American Gangster,” but it does perpetuate this notion of the kind of glamorous, killing machine that is at the root of drugs and I think is often part of the popular perception.

Yeah, but it does that in the middle of an argument that the U.S. government aided and abetted the injection of drugs into the inner cities. This is an extraordinarily dark aspect of the American story, one so dark I was probably too cowardly to go into it in my movie, and yet that movie, for all of its other Hollywood tropes, notwithstanding that, went into some very intense territory there. And I don’t think portrays Frank Lucas as a hero. I think it portrays Frank Lucas as a human, and as such, he does some stuff which looks and feels like a movie because there’s killing and there’s cut-throatedness, but he also is a human being trapped inside a cycle of ongoing degradation and despair in the African American community. So for him to want to get his, but he does so at the expense of his own people. That is the bitter irony of that character and it is a super-sensitive movie to have understood that. Look, Hollywood is what it is, it needs to sell some tickets, they’re going to do certain things that are conceits that are time-proven, and I don’t want them to do that. But if you gave me the choice to not have a movie or have a rather substantive movie like “American Gangster” that’s going to have just enough of those to get over and get some box-office, I’ll probably choose the second because this needs to be more talked about, not less, and I’ll lose my religion over some of those details.

You have mentioned Portugal as a good counter-example to the US approach of criminalization. Tell me a little bit about what they do well.

They pursued wholesale decriminalization, and you can Google the statistics online. The statistics of success in Portugal, in the early phases but relatively substantive phases of their process, are exemplary. And they speak to the possibility, they speak to what all of us would know to be the case, I mean, we’ve learned in New York City for example, that one of the primary determining factors of why New York City has a reduced crime rate over what it had in the past is that New York State is one of the only states in the country that has actually reduced its prison population. We know in this country statistically from criminology that the prison is criminogenic, that prisons create more crime. So this mass incarceration system creates a spiral towards increased crime and increased incarceration, and when you reduce it, you defuse that spiral, you de-energize that spiral and so when you see other countries in the world that, from a starting point, don’t have our commitment to mass-incarceration and from a starting point do not have industrialized systems of mass-incarceration like ours, you already see that they don’t have that kind of explosive tragedy unfolding and that means their spiral is not getting worse and worse all the time as ours is.

You touch on some very important stuff in the movie, the follow-the-money incentives, like federal programs now that reward local jurisdictions based on the number of drug arrests that they make.

Michelle Alexander talks about them in her book, The New Jim Crow, and she talked to me quite a lot in our interview with her, that stuff was a little bit in the weeds, it’s so specific. But yes, the grant programs that reward police departments for increased drug arrests create a climate of incentivized, low-level law enforcement harassment, so it should be no wonder, for example, that in New York City, we have several hundred thousand stops a year, 350,000 of them become frisks. Of these, 90% of these people are young blacks and Latinos. Of those 350,000 frisks a year, only 10% lead to an arrest. So 90% are just harassment. This is a grotesque system. So once you know that that’s at work, this has to be stopped.

Are there any politicians who are on-front in this issue or are they all terrified?

Congressman Bobby Scott is an exemplar on the matter of the drug war. Senator Jim Webb, who could not get sufficient support for his omnibus crime bill, but should, and should be given support for the setting up of a blue-ribbon commission to study our criminal justice system and overhaul it. Cory Booker’s one of the leading voices against the drug war in the nation and from his mayorship in Newark. And there are others across the country in their small ways, here and there, who matter deeply and who’ve gone up against the country’s drug policies. And the occasional judge will do that, and the occasional public figure will do that, but of course, it’s far too few. The real headline is, it’s far too few.

What do you think the fascination is with shows like “Weeds” and “Breaking Bad” in glamorizing small-time drug-dealers?

I think people are fascinated by drugs in America. We’re one of the most addicted countries in the world for a lot of reasons. I think drugs are a place that despairing people find solace in and escape, I think there’s an increasing level of despair in this country over a sense of existential meaninglessness. The point of being a country has been undermined by capitalism in this country.

Posted on October 11, 2012 at 6:56 pm

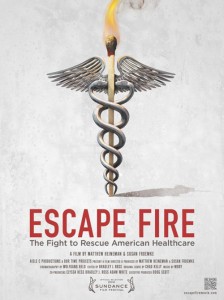

“Escape Fire” is a new documentary about what does not work in our system for preventing and treating illness, and what some people are doing to make it better. I spoke to Matthew Heineman, co-director and co-producer of the film.

Tell me about the reactions you have been getting from people who see this film.

I think one of the most inspiring things for us is to really see what happens when a local community screens the film. Just two weeks ago we screened the film at 62 medical schools across the country, all on one night. There is an outpouring of optimism, that this is a problem that we can fix, a problem that we don’t have to wait, necessarily, for someone to come in from Washington, that change can really happen on the local level, sort of doctor-by-doctor community, system-by-system, and that’s how change can happen quickly. One of the real goals of the film is to transform how our country views health and habit. Medical school is the future, so their response is important. We also screened last week at the Pentagon, hosted by the U.S. Army Surgeon General, and have sort of a room full of leadership generals and medical leadership at the Pentagon. And again, they recognize this problem that they have with over-medication, recognize that the status quo’s not working, and the Surgeon General said herself that she really thinks that this film can help change the culture of medicine in the army to begin with, but hopefully with the military at large. So it’s pretty amazing, we’re already seeing impact happening.

A big light-bulb moment for me comes fairly early in the film when somebody says, “We don’t have a healthcare system, we have a disease-management system.”

We did 6-8 months of research on the topic and almost everyone was saying that. It’s a system that profits from sickness, not on health. 75% of healthcare costs go to preventable diseases, so how did this system come to be? Why did it not want to change? We wanted to try and find people out there who are trying to change it. Just to quickly mention one thing I didn’t say about your first question,

It seems to be that the problem which you touch on in the last part of the film, the inevitable corruption of corporate money and politics, is the real insoluble problem. You can have the good will in the world and you can have all the data in the world, but when people are getting paid hundreds of millions of dollars under the current system, it’s very hard to get them to change it.

There’s no question about that. As Andrew Weil says in our film, there’s rivers of money flowing to very few pockets, and the owners of those pockets don’t want to see anything changed. I think what’s different now, and one of the reasons why we made the film is that things can’t get any worse. We’re spending 2.7 trillion dollars a year on healthcare. That’s just a number, but when it comes down to individual companies or healthcare systems or cities or towns or small businesses or individual people, it’s bankrupting us. So, we’re being forced to change, we’re being forced to adapt, because what’s happening now is unsustainable. We see that with the military in our film, we see that with Safeway Corporation in our film, we see that at the Cleveland clinic, that these major institutions are being forced to change, and so I think, yes, the system is making a lot of money out of the way things are, but many of the players in the system recognize how unsustainable it is and thus are being forced to change.

Your movie makes the case that when you spend more money it doesn’t necessarily correlate to better outcomes.

That was one of the most eye opening things for us. In America we have this fascination with faster, bigger, better, now; we want the quick fix. We want that pill, we want that procedure, we view healthcare as something that somebody gives to us or does to us or something that we put in our throat, and I don’t think we really recognize that more isn’t necessarily better when it comes to healthcare, that more can often hurt us, that there’s this term called ‘over-treatment.” We reward for quantity and not for quality. Doctors, we pay for the diabetics to get their foot amputated when they’re 60, but we don’t pay for simple nutritional counseling when they’re 20, 30 or 40 to prevent that from happening in the first place. It’s just a perverse system.

What got you interested in this as an issue?

We started the film three years ago just as the healthcare debate was heating up, and I think like many Americans we were just confused by the traditional media coverage of the topic, I mean, it was so hyperbolic and so confusing; healthcare was really dividing our country. So, I think we really wanted to try to understand, systemically, how it was broken, why it was broken, but also highlight people out there who were trying to fix it. So many films like this are just polemics, that you walk out of there, head hanging low and just hopeless, and I think we knew from day one that we didn’t want to do that. We also knew from day one that we wanted to have real, powerful human narratives that would provoke audiences to want to keep watching.

What can a movie do that an op-ed or book or politician could not do?

I’m obviously biased; I’m a film-maker. I think documentary film has the power to really bring an issue that to life, with real human stories in a way that facts or articles or tweets don’t or can’t. What we really tried to do was make a film that would not only move you intellectually but move you viscerally. We look at healthcare through a number of different lessons and through a number of different characters that I think almost anyone in American can identify with, at least one, two, three or all of our characters in this film and say, “I know somebody like that,” “that’s sort of like me.” It is just the power of film to associate at a more visceral level with an issue. I think that’s what documentary has the power to do.

Why did you choose to name the film after a technique for stopping a forest fire by setting a small controlled “escape fire?”

Escape fire is a metaphor between our healthcare system and a forest fire from 1949 that happened in Mann Gulch, Montana. The fire fighters were filled with hubris, with the latest and greatest technology, they thought they’d have it beat by 10 o’clock the next morning—then the wind shifted directions and they found themselves running down this hill for dear life. The foreman, the leader of this group, came up with this ingenious idea on the spot, where he lit a match and he burned the area around him to consume the fuel, so that when the fire came over to them, he’d be safe in what is now known as an “Escape Fire.” He called to allow his fellow smoke-jumpers to join him, but nobody listened, and they kept running up the hill. They all died, but he survived, basically, unharmed. And I think it’s a really powerful metaphor because it shows that the status quo is so strong, especially in healthcare, it’s so easy to keep doing what we’re doing, and we’re making a lot of money continuing to do what we’re doing, but we really need to look outside the box and think outside the box to come up with an escape fire for our system. Otherwise we’re doomed.

Posted on September 13, 2012 at 8:00 am

I was moved and inspired by Roger Ebert’s book Life Itself: A Memoir and I’m thrilled to hear that it may become a documentary thanks to three brilliant filmmakers, Martin Scorsese (“Goodfellas,” “Hugo,” “Raging Bull”), Steven Zaillian (“Schindler’s List,” “Moneyball,” “Searching for Bobby Fischer”), and Steven James of “Hoop Dreams.”

According to Ebert’s paper, the Chicago Sun-Times, Ebert said,

“When I first learned they were interested, the news came out of a clear blue sky,” Ebert wrote in an e-mail. “I once wrote a blog about Steve James’ ‘Hoop Dreams,’ calling it the ‘The Great American Documentary.’ His ‘The Interrupters,’ about volunteers trying to stop street violence in Chicago, is urgent and brave. Now to think of him interested in my memoir is awesome. Zaillian and Scorsese are also brilliant filmmakers. I couldn’t be happier, especially since I never thought of ‘Life Itself’ as a film.”