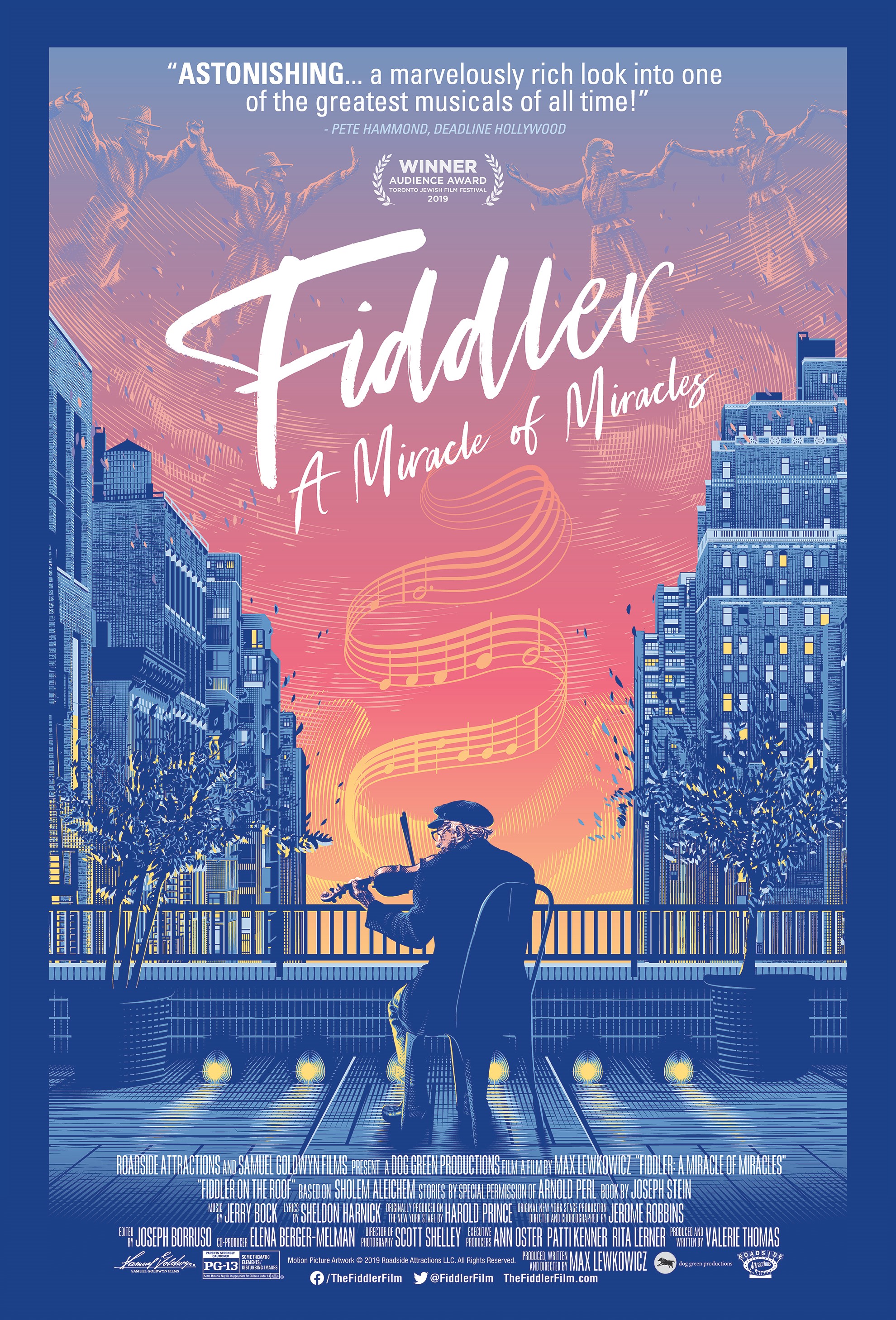

Fiddler: A Miracle of Miracles

Posted on September 8, 2019 at 5:10 pm

B +| Lowest Recommended Age: | Middle School |

| MPAA Rating: | Rated PG-13 for some thematic elements/disturbing images |

| Profanity: | Brief strong language |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Social drinking |

| Violence/ Scariness: | Images of pogroms and references to the Holocaust |

| Diversity Issues: | A theme of the movie |

| Date Released to Theaters: | September 13, 2019 |

“Fiddler on the Roof” opened on Broadway in 1964 and every single day in the over half a century since then it has been performed somewhere. Even more impressive, it has been performed pretty much everywhere, and is currently back in New York with an off-Broadway all-Yiddish version directed by Joel Gray. In this engaging new documentary about the history and continuing cultural vitality of the musical based on the stories of Yiddish author Sholom Aleichem about the families in a Russian Jewish shtetl, we see productions in Japan, Thailand, and in a student production with an all-black and Latinx cast. We see Puerto Rican “Hamilton” creator Lin-Manuel Miranda singing “To Life” to his Dominican/Austrian-American bride at their reception, in a YouTube video with over 6.5 million views.

“Fiddler on the Roof” opened on Broadway in 1964 and every single day in the over half a century since then it has been performed somewhere. Even more impressive, it has been performed pretty much everywhere, and is currently back in New York with an off-Broadway all-Yiddish version directed by Joel Gray. In this engaging new documentary about the history and continuing cultural vitality of the musical based on the stories of Yiddish author Sholom Aleichem about the families in a Russian Jewish shtetl, we see productions in Japan, Thailand, and in a student production with an all-black and Latinx cast. We see Puerto Rican “Hamilton” creator Lin-Manuel Miranda singing “To Life” to his Dominican/Austrian-American bride at their reception, in a YouTube video with over 6.5 million views.

We hear the show’s creators and performers talk about what it means to them. Since the earliest part of the 20th century, Jewish composers and lyricists including Irving Berlin, Oscar Hammerstein, Richard Rodgers, Fritz Loewe, and more wrote huge hit Broadway shows about cowboys, Thai kings, an Italian mayor of New York, Pacific Islanders, and a sharpshooting hillbilly. Finally, it was time to write their own story, the story of the Jews who lived in tiny towns in Eastern Europe until anti-Semitic gangs and local governments pushed them out. And so they were ready to tell the story of their parents and grandparents, just as those stories seemed vitally important again.

So we see again what has made this story so vibrant over the decades. “What is this about?” director/choreographer Jerome Robbins repeatedly asked the show’s creators, Sheldon Harnick (lyrics), Jerry Bock (music), and Joseph Stein (book). They tried different answers — about the poor father of daughters who have their own ideas about who they should marry or about Jews struggling in a country that is increasingly hostile to them. He asked them again until they finally came up with the right answer and it was just one word: tradition. That, of course became the iconic opening song in the play.

My parents saw the original production of “Fiddler” on Broadway and bought the cast album, which our family played constantly. I played the part of the oldest daughter in a religious school production and then our daughter played the same role in her middle school version. We have all seen it many times, and my parents saw a production in Tokyo with an all-Japanese cast my parents saw, where Tevye sounded like TV. They asked a member of the audience why it was so popular in Japan and they got the same answer someone in this movie did, “Because it is so Japanese.”

The fringes on the prayer shawl and the words of the prayers may be different, but every family has had to resolve conflicts between the generations and every individual has had to face the existential question of which traditions provide a foundation of our identity and connect us to our culture and which have to be adapted or abandoned, which aspects of our culture hold us up and which hold us back.

In “Fiddler,” we see three conflicts as Tevye’s three oldest daughters fall in love. The oldest refuses an arranged marriage with an older, wealthy man and asks her father to approve her marriage to the poor tailer she loves. Then the second says she will marry the hotheaded revolutionary she loves, and she does not want her father’s permission, only his blessing. He gives it to them. But when the third daughter wants to marry a man who is not Jewish, that is something he cannot accept. Meanwhile, Russian anti-Semitism is growing, and it is no longer possible for the Jews to stay in the only home they have ever known. When the play was first produced in 1964, the world was still learning about the breadth and damage of the Holocaust (the term itself was still not widely used), and the State of Israel was just 16 years old and still perilous. The story was at the same time charmingly nostalgic, painfully topical, poignantly personal (everyone understands “Sunrise Sunset”), and meaningfully universal. The documentary shows the contributions of the extraordinarily gifted people who created the show (touchingly, director/choreographer Jerome Robbins, a Jew born Jerome Wilson Rabinowitz, was inspired in part by visiting the town his family came from, wiped out in the Holocaust), and the impact the show has had around the world, always resonating with contemporary concerns. But most of all, it reminds us of why it is so enduring simply through the characters, story, and music that will still be touching audiences in another 50 years.

Parents should know that this film has references to theatrical and historic tragedies and atrocities.

Family discussion: When did you first see “Fiddler” or hear its songs? What are your favorite traditions?

If you like this, try: the movie version of “Fiddler on the Roof” and a theatrical production — there should be one near you.