The Appeal and Frustration of Ambiguous Movie Endings

Posted on November 1, 2011 at 8:00 am

I like Ann Hornaday’s piece in the Washington Post about ambiguous endings.

In “The Film Snob’s Dictionary,” writers David Kamp and Lawrence Levi cheekily chart out the differences between Movies and Films (“It’s a Movie if it’s black-and-white because it’s old. It’s a Film if it’s black-and-white because it’s Jarmuschy.”) They might have added another definition: It’s a Movie if it ends. It’s a Film if it stops.

Studio films tend to spell everything out — motivations, backstories — while independent films invite the audience to fill in the blanks or just ponder the unanswerable. One reason for that is money. Studio films are expensive and have to appeal to the broadest possible audience. The more money you spend, the more people weigh in on the film’s artistic choices, and the more people weigh in, generally speaking, the more questions get answered on screen.

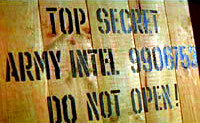

Of course, even the most definitive-appearing ending leaves a lot open for discussion. Does finding out what “Rosebud” means in “Citizen Kane answer a question or raise a dozen more? What happens after Rhett tells Scarlett he does not give a damn what happens to her? Does anyone ever open that crate in the government warehouse and find the Lost Ark of the Covenant? What exactly does “happily ever after” mean?

Of course, even the most definitive-appearing ending leaves a lot open for discussion. Does finding out what “Rosebud” means in “Citizen Kane answer a question or raise a dozen more? What happens after Rhett tells Scarlett he does not give a damn what happens to her? Does anyone ever open that crate in the government warehouse and find the Lost Ark of the Covenant? What exactly does “happily ever after” mean?

Hornaday discusses some of this year’s most open-ended movies, including “Take Shelter,” “Martha Marcy May Marlene,” and “Meek’s Cutoff.” I love to come out of a movie and talk about what I think happens next, don’t you? Do you have a favorite theory about an ambiguous ending?