The Fifth Estate

Posted on October 17, 2013 at 6:05 pm

B| Lowest Recommended Age: | High School |

| MPAA Rating: | Rated R for language and some violence |

| Profanity: | Very strong language |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Drinking |

| Violence/ Scariness: | Some violence including murder of two people and footage of military killings |

| Diversity Issues: | None |

| Date Released to Theaters: | October 18, 2013 |

| Amazon.com ASIN: | B00BEIYRYM |

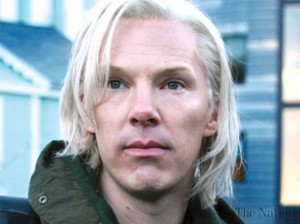

In late medieval times, when people first began to divide each other into groups defined by status and power, they began to speak of a “first estate” (the clergy), a “second estate” (the nobility, which also at the time meant the government), and a “third estate” (the common people. Later, the “fourth estate” was added to describe journalists and what today we call news media. Julian Assange, the Australian teenage hacker turned founder of Wikileaks is singular, unprecedented, gui generis. He collects masses of “secret” data and publishes it without editing, digesting, analysing, or redacting any of it. And so, this movie, with Benedict Cumberbatch as the white-haired Assange, is called “The Fifth Estate.”

In late medieval times, when people first began to divide each other into groups defined by status and power, they began to speak of a “first estate” (the clergy), a “second estate” (the nobility, which also at the time meant the government), and a “third estate” (the common people. Later, the “fourth estate” was added to describe journalists and what today we call news media. Julian Assange, the Australian teenage hacker turned founder of Wikileaks is singular, unprecedented, gui generis. He collects masses of “secret” data and publishes it without editing, digesting, analysing, or redacting any of it. And so, this movie, with Benedict Cumberbatch as the white-haired Assange, is called “The Fifth Estate.”

This movie, from director Bill Condon (“Kinsey,” “Dreamgirls”), and based on a book by Assange’s now-estranged former partner Daniel Berg (played in the film by “Rush’s” Daniel Brühl) at times feels as though it is un-digested and un-analyzed. As a government official forced to resign due to some of the disclosures says near the end of the film, “I don’t know which of us history’s going to judge more harshly.” I would advise anyone interested in Wikileaks to begin with the documentary, “We Steal Secrets: The Wikileaks Story,” directed by Alex Gibney.

Assange says that he has two goals for what he calls “a whole new form of social justice.” He says he wants transparency for institutions and privacy for individuals. The problem, or, at least, one problem is that institutions are made up of individuals. And so, when one of Wikileaks’ early scoops is a list of British members of the far right “National Party,” it does not bother him that the members’ contact information is disclosed. Assange is an absolutist. He refuses to edit or redact (remove identifying information from) any of the documents he publishes. “Editing reflects bias,” he says. He is also something of a monomaniac and a megalomaniac, at least in the view of his one-time colleague. According to this film, he grew up in an odd Australian cult called “The Family,” with severe beatings, and has been diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum. He is very protective of his own privacy as he exposes the secrets of others. And, as they say, just because you’re paranoid does not mean they’re not really out to get you. Once Assange starts exposing the secrets of the wealthy and powerful, they start coming after him, and the thing about being wealthy and powerful is that they have the resources to inflict a lot of harm. Two of his sources are murdered.

Condon does his best to minimize the scenes of people staring intently into monitors while they bang on the keyboards. He has some nice visualizations to evoke the experiences, some fantastic, some just the rocky topography of Iceland, one of many places Assange hid. And he takes a balanced approach. Everyone would agree with some of what Assange has uncovered. And everyone would object — even be horrified — by something he has done. Both sides quote Orwell. Big Brother is watching. Like “The Social Network,” the movie focuses on the rise and fall of the friendship and partnership more than the impact of the product they were working on. In this case, that is in part because we don’t know what that impact will be. But in this case, we do know that the impact is transformational. This is not some Facebook advertiser using an algorithm on your status posts to figure out what to sell you. This is a 22-year-old destroying the confidentiality that allows candid conversations between diplomats, including information about the foreign nationals who are giving them information.

Assange explains early in this film that the program he has developed to protect the identity of the providers of leaked documents is to drown them in false and phony data. He can say that editing reflects bias, but in the case of terabytes of information dumped in undigested and unredacted form, the data dump can be just as distorting. Like the journalists Assange worked with on the Bradley Manning material, this film tries to put some shape and perspective on a story that is still too big and too new to frame as a definitive narrative. But it is an absorbing story and as good an assessment as we can get for now.

Parents should know that this film has very strong language, violence including shooting and wartime scenes with some disturbing images.

Family discussion: What is the answer to the State Department official’s question about whose side history will be on? Who should decide what gets released? If Wikileaks makes other organizations accountable, who makes Wikileaks accountable? Do you agree with the two things Assange says you need to have to succeed?

If you like this, try: the documentary “We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks,” read up on the most recent leaker, Edward Snowden, and take a look at the Wikileaks page