Watching “12 Years a Slave” is a shattering experience. It shatters any remaining illusions of gracious, chivalrous, Southern plantation life in the pre-Civil War era. They were based on the late 19th century myth-making from the children of slave-owners in a toxic effort to disguise the reality that the South was fighting to preserve a system of virulent racism fueled by the economics of plantation life. It shatters cherished notions of the first principles underlying the founding of this country. The man who wrote the revolutionary words that “all men are created equal” was a part of this atrocity. It shatters all previous depictions of slavery. By comparison they seem cartoonish and fraudulent, from “Gone With the Wind” to “Django Unchained,” more about the time they were made than the time they depicted. And, like all great films, it shatters our previous notions of what was possible on screen, with performances so vivid and compelling they seem to break through every boundary, between us and them, between then and now, between actor and audience. In one audacious moment, Solomon Northrup (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a free man sold into slavery, looks into the distance, eyes filled with ineffable suffering and loss, and then turns to face us, looking into the eyes of those who are looking at him, bringing us further into his world.

Watching “12 Years a Slave” is a shattering experience. It shatters any remaining illusions of gracious, chivalrous, Southern plantation life in the pre-Civil War era. They were based on the late 19th century myth-making from the children of slave-owners in a toxic effort to disguise the reality that the South was fighting to preserve a system of virulent racism fueled by the economics of plantation life. It shatters cherished notions of the first principles underlying the founding of this country. The man who wrote the revolutionary words that “all men are created equal” was a part of this atrocity. It shatters all previous depictions of slavery. By comparison they seem cartoonish and fraudulent, from “Gone With the Wind” to “Django Unchained,” more about the time they were made than the time they depicted. And, like all great films, it shatters our previous notions of what was possible on screen, with performances so vivid and compelling they seem to break through every boundary, between us and them, between then and now, between actor and audience. In one audacious moment, Solomon Northrup (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a free man sold into slavery, looks into the distance, eyes filled with ineffable suffering and loss, and then turns to face us, looking into the eyes of those who are looking at him, bringing us further into his world.

This is different because it is a rare story of pre-Civil War South told from a black person’s point of view. It is based on Northrup’s book , written after he returned to his family. It is the story of slavery from a man who experienced it, and who knew what it was like to live as a black man who was not just free but better educated and more successful than most people of any race in his community. In that sense, it is a story told from inside the system of our country’s greatest shame. In another sense, it is presented by outsiders, director Steve McQueen (British) and stars Ejiofor (the British son of Nigerian immigrants) and Lupita Nyong’o (born in Mexico, raised in Kenya, educated in the US). They tell us Northrup’s story — and ours — without being tied to the way we prefer to tell ourselves what our history is and means.

, written after he returned to his family. It is the story of slavery from a man who experienced it, and who knew what it was like to live as a black man who was not just free but better educated and more successful than most people of any race in his community. In that sense, it is a story told from inside the system of our country’s greatest shame. In another sense, it is presented by outsiders, director Steve McQueen (British) and stars Ejiofor (the British son of Nigerian immigrants) and Lupita Nyong’o (born in Mexico, raised in Kenya, educated in the US). They tell us Northrup’s story — and ours — without being tied to the way we prefer to tell ourselves what our history is and means.

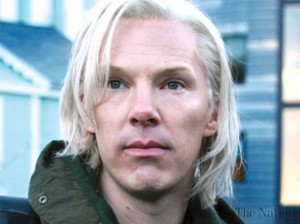

Northrup is a successful musician, happily married with two adored children and respected by both white and black members of his community in New York State. He accepts a job playing with some circus performers (Scoot McNairy and “SNL’s” Taran Killem) in Washington, D.C., where slavery is legal. They drug him and sell him to a slave dealer (Paul Giamatti). Without his papers, he cannot prove he is a free man. Soon he is renamed Pratt and transported to Louisiana, where he is sold first to a comparatively benevolent man (Benedict Cumberbatch), but then, when he gets into a fight with the overseer (an oily Paul Dano), he is re-sold to a brutal man who prides himself on being an n-word-breaker (Michael Fassbender). Northrup loses more than his family, his liberty, his name, and his freedom. He loses his very self; he is told early on that if the white people know he can read and write, it will create more trouble for him. Indeed, when he tries to be helpful by suggesting a better system for transporting the crop, he earns the gratitude of his master but incurs the jealousy of the white boss. The only way to survive is to pretend to be the sub-human the owners need them to be to continue to hold onto their bigotry.

This movie makes clear the poisonous, psychotic twisted mind that can accept or even justify the idea that one person can buy and sell another. Over and over, we see the slaveholders at the same time acknowledging and denying the humanity of the people they think they own. A female slave sobs because her children have been sold and she will never see them again. The woman of the plantation, briefly sympathetic, says, “Poor woman.” But then, immediately after, “Your children will soon be forgotten.” Slaves are included in family worship services (though not seated with the family). But their souls are never acknowledged; they are categorized as livestock.

There are terrible beatings. There is torture and rape. Slave children run and play, laughing, ignoring the man who is almost choking to death as punishment. There are property identification chains slaves must wear if they go off the property, like something between a hall pass and a dog tag. There is a slave who has made her peace with what she has done to get better treatment — and with what she now does to other slaves.

Instead of the lush orchestral score usually underlying period films or the melancholy flute and drum usually heard in Civil War films, Hans Zimmer has created spare, edgy music that is bleak without being maudlin. McQueen’s approach is sure and direct and the script by John Ridley is ably structured and thoughtful. Nyong’o’s gives performance of exquisite grace and heart-wrenching dignity. But the center of the story is Northrup. Ejiofor is sure to get an Oscar nomination for a performance of unparalleled depth and eloquence.

Parents should know that this film includes very graphic and disturbing images of slavery, with rape, murder, and abuse, brutal whipping and atrocities, nudity, sexual references and situations, constant racial epithets, drinking and drunkenness.

Family discussion: What was the significance of the early scene in Mr. Parker’s store? How does this story differ from other movie depictions of the pre-Civil War South? Why did Northrup join in the singing of “Roll, Jordan, Roll?”

If you like this, try: book by Solomon Northrup , “Amistad,” American Experience: The Abolitionists

, “Amistad,” American Experience: The Abolitionists , and Roots

, and Roots