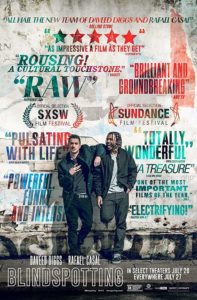

Blindspotting

Posted on July 19, 2018 at 5:31 pm

B +| Lowest Recommended Age: | Mature High Schooler |

| MPAA Rating: | R for language throughout, some brutal violence, sexual references and drug use |

| Profanity: | Very strong, crude, and racist language |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Drinking and drunkenness, drugs |

| Violence/ Scariness: | Peril and violence including policeman shooting an unarmed man |

| Diversity Issues: | A theme of the movie |

| Date Released to Theaters: | July 20, 2018 |

| Date Released to DVD: | November 19, 2018 |

Collin (Diggs), who is black, has just three more days of his year-long probation, following a two-year sentence. As long as he meets every checkpoint and follows every rule for just three more days, he will be able to leave the closely supervised halfway house and regain his freedom.

This is a challenge. His best friend Miles (Casal), who is white, is completely loyal to Collin but also impulsive and naturally resistant to any kind of rules. Collin finds himself with Miles and another friend who are smoking weed and playing around with guns. If he is discovered, it would mean an immediate return to prison. And then it gets worse. Collin, already running late getting back to the halfway house, knowing that missing curfew is a probation violation, stops at a red light and sees something he shouldn’t — a white cop killing an unarmed black man. The cop spots him and tells him to go. Terrified of getting shot or going back to prison, he does.

Collin and Miles work as movers, which gives us a chance to see the gentrification of Oakland, from the ten dollar “green juice” drinks suddenly appearing in local stores to the artist (Wayne Knight) who shows them his pictures of the trees that once gave the city its name but have now been cut down for development. A character wears a t-shirt that says, “Kill a hippie; save your hood.” The feeling of displacement is personal as well. Collin’s mother has remarried and her new stepson has moved into his old bedroom.

In some respects, the community is generously diverse. Colin’s black mother is now married to an Asian man. Miles is devoted to his partner, who is black, and their son. But racial divides persist, and this film navigates them and addresses them with a deep understanding of the history and complexity. When the friends finally get into a fight that could divide them forever, it is in large part because even the closest of friendships, even those who feel like family cannot truly understand what it is like to be black unless they are black.

At one point, a character asks Miles and Collin to stand quietly and look deeply into each other’s eyes. As much as these two men share, it is rare for them to look at each other. When they speak, they are often both staring ahead. This movie, conceived a decade ago but somehow coming out at exactly the right time, asks us to look deeply at both of them, and thus at ourselves.

Parents should know that this movie includes peril and violence, very strong, crude, and racist language, drinking and drunkenness, drugs, and family conflict.

Family discussion: What are the pros and cons of gentrification? What should Collin have done when he saw the officer shoot an unarmed man?

If you like this, try: “Do the Right Thing” and “Sorry to Bother You”