Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts

Posted on April 15, 2021 at 6:15 pm

B| Lowest Recommended Age: | Middle School |

| MPAA Rating: | Not rated |

| Profanity: | Some racial epithets |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Alcohol |

| Violence/ Scariness: | References to lynching and abuse |

| Diversity Issues: | A theme of the movie |

| Date Released to Theaters: | April 16, 2021 |

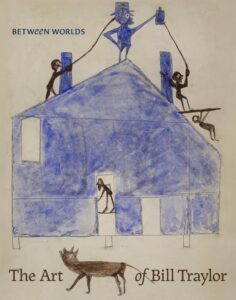

Outsider artist Bill Traylor was born into slavery. Traylor was the name of the white family that enslaved him and his family. They were more benevolent than some; the plantation owner’s will provided that Bill Traylor’s family should not be split up when they divided the estate. And so, even after emancipation, Traylor’s family stayed, working as field hands and then as tenant farmers. He lived his whole life within 40 miles in Alabama, farming until he was too old and infirm. And then he spent the rest of his life in a vibrant Black community in Montgomery, fed by a deli owner and sleeping on the floor of another business, drawing and painting all day out on the sidewalk, with whatever materials were available to him, including bright blue poster paint given to him by a teenage sign-painter and torn off pieces of cardboard signs.

“Outsider art” is work created by people who are untrained, self-taught, not a part of the art community, creating art for themselves, not for galleries or museums. We do not know what Traylor would think about the way his work is revered today. In this documentary, directed by Jeffrey Wolf and executive produced by artist Sam Pollard, we hear a story of the one time he did see his work on the walls of a gallery and, according to legend “did not recognize it.” But the commentary in the film suggests that it was not is work he did not recognize but the setting that displayed them. He would be even more amazed at the seriousness with which his work is discussed by artists, curators, and scholars in this film.

I attended the first major show of Traylor’s work, at the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. As they pointed out, The paintings and drawings he made are visually striking and politically assertive; they include simple yet powerful distillations of tales and memories as well as spare, vibrantly colored abstractions. When Traylor died in 1949, he left behind more than one thousand works of art. The simplified forms of Traylor’s artwork belie the complexity of his world, creativity, and inspiring bid for self-definition in a segregated culture.” His is the only substantial art we have from someone born in to slavery, and it is important as art and artifact, giving us a vital chance to see the world the way he did.

This film wisely takes a multi-faceted approach to Traylor’s life and work, incorporating music, dance, poetry, and commentary from historians, critics, curators, scholars, other artists, and Traylor’s own descendants. Some of the historical material is as illuminating for what we do not know as for what we do; the records of the lives of Black Americans during this period are very limited. And some of the expert commentary is more heartfelt than insightful. The best art produces an emotional connection that cannot be reduced to language. Appropriately, inevitably, what is most eloquent here are Traylor’s images themselves.

Parents should know that this film includes discussion of enslavement, lynching, Jim Crow laws, and racism as well as Traylor’s multiple children by different women.

Family discussion: Which of Traylor’s paintings did you like the best? Why wasn’t he seen as an important artist in his lifetime? What pictures can you create about the world you remember?

If you like this, try: “The Realms of the Unreal” about another outsider artist, Henry Darger