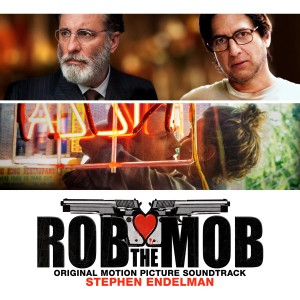

“Rob the Mob” is a fact-based story about a couple named Tommy and Rosie who thought they had a foolproof way to make some money. Since Mafia members were not allowed to bring weapons into their social clubs, why not rob them there?

“Rob the Mob” is a fact-based story about a couple named Tommy and Rosie who thought they had a foolproof way to make some money. Since Mafia members were not allowed to bring weapons into their social clubs, why not rob them there?

Yeah. It does not sound like a good idea to me, either. But what is a good idea is making a movie to tell their story, starring two exceptionally gifted and charismatic young actors, Michael Pitt and Tony-winner Nina Arianda. I spoke to the man who composed the film’s score, Stephen Endelman.

How did you get involved with this project?

I worked with Raymond first on “Two Family House.” That was a very pleasurable experience and then there was another one in between that I couldn’t do which was “City Island,” which is actually a really good movie. This is the best of all, this is I think, well not just me, a lot of people are talking about what a great movie it is and it is. I got involved with Raymond, he showed me the script, I read the script and I said, “Raymond, I have to do this movie.” He said, “I want you to do it, it’s not a question, you don’t have to tell me that”. And I said, “Great.” Then he came to my studio and he said “Stephen, I have got an idea. I said, “Fire away.” He said, “How about I come here with David Leonard and I’ll set up in your other room, and you be in your room, I’ll be in this room and you write music and I’ll cut. I’ll do this for six weeks and then I’ll go back to New York for the last three weeks.” And I said, “You make that happen, I’ll be thrilled. What a creative way to work.”

And so that’s what happened. And so he came here. I had seen a lot of footage as they were shooting. And I was writing, there was never any temp score at all. Five weeks after Raymond got here, the producer got here, we showed him a cut and it was like seeing the movie, all my music, all we needed to do was to refine it at that point, cut the movie down and refine it.

That’s very unusual, isn’t it?

That’s deeply unusual and it shouldn’t be. It should be the only way to work.

Tell me what the benefits are of doing it that way.

The problem with a lot of films today in my opinion and Raymond’s actually is that they are so used to doing things with a temp dub that by the time they hire a composer they are married to the temp score. So 80 percent of the time if not more composers are really just copying the scores with a few modifications. I have made a career of not doing that from day one. “Household Saints” — I saw the movie I wrote the score then the next movie, The Englishman Who Went Up A Hill But Came Down A Mountain , there was no score. Chris Mundell didn’t want to temp the movie at all and so when I got that job I just got a blank canvas. Raymond’s was the same. David Russell’s Flirting With Disaster

, there was no score. Chris Mundell didn’t want to temp the movie at all and so when I got that job I just got a blank canvas. Raymond’s was the same. David Russell’s Flirting With Disaster was the same. What actually was not the similar way from working with Raymond was that he was downstairs in the film station editing and I was writing. But it’s the only way to work. And actually when I think about it, you know what at A Bronx Tale

was the same. What actually was not the similar way from working with Raymond was that he was downstairs in the film station editing and I was writing. But it’s the only way to work. And actually when I think about it, you know what at A Bronx Tale they brought me into the Brill Building six weeks so we’d build it together.

they brought me into the Brill Building six weeks so we’d build it together.

When you’re doing a crime story, how do you begin to think about what tone you want to achieve and how you want to set the stage?

When you think of crime movie, there are going to be robberies. From day one Raymond and I said, “No, we’re not going to do it like that because this is not a conventional mob crime movie.” This is about two young people who are madly, hopelessly in love, right? They are hopelessly in love and they have decided to rob the social clubs when they learned from Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, there were no guns in clubs.

Wise guys and guns in clubs don’t go together. So Tommy thinks it will be easy to rob them. Tommy takes their money, he humiliates them. Because his father was basically tortured to death, there’s a kind of vengeance level there. And the crime involved was just palpable so I said look we have to write a very memorable love scene. So that basically takes care of them. Element number one, their love scene. We hear snippets of it throughout the movie and at the end you get the big impression of it, that’s one level.

Then the other level, what do we do about the scary wise guy? So the biggest and the scariest of the wise guys is Andy Garcia who plays Big Al. Big Al isn’t scary anymore. Big Al is coming to term with the fact that his son is dead, what he’s got is his grandson. All he wants to do is make food in the kitchen, look after his little boy. That doesn’t need action. That needs a delicate touch because really you want to feel for Big Al, you wanna feel his relationship with his grandson, and then his dead son and you do feel that. Then you have those robberies, and in order to get the robberies where we want then Raymond had a song and we decided to, he wanted an Italian style, an Italian pop song from the 60’s. He thought the guys would be listening to that and it would be an Italian. And Raymond said “Why don’t we just write it?” So I said, “Fine.” e came up with the lyrics and I wrote the music. We have three songs in the movie. When they go to do the robberies, then you have the level of the robberies themselves and that’s the only tense music in the movie but even that is not really that tense. That’s kind of percussive with a lot of other stuff going on. It’s very rhythmic, it’s not angry, there’s no anger. It didn’t need that and the score didn’t need that. The score needed to be beautiful, and it needs to let you inside the inner voices of all the characters. The wise guys are sad, they are sad and they are old, and Rosie is crazy in love and silly and that’s kind of the tapestry there I think.

So it’s really a love story?

It is a love story; I think it is a love story.

What’s the best advice you ever got about writing for films?

The best advice I ever got about writing for film didn’t come from a film composer. Morton Feldman was one of great American classical composers, somebody who taught me for a little while. He said, “Stephen, there’s no such thing as funny music.” I thought about that because you know, of course there’s cartoon music and can you imagine that’s funny but of course he’s right, there’s no such thing as funny music.

So what did I do? I translated that as you’re building a score of funny theme or if you’re gonna try then you have to think about timing completely and less about what’s funny in the music. Because there’s no such thing as funny music, that’s nonsense and so that idea was really important because I never really studied song composing, I never really went to school, I studied with composers to be a composer. I saw myself doing film because I always loved films.

I became really interested in film music when I saw the uncut version of “Once Upon a Time in America.” Just watching that I realized, “Wow, that could just as easily been written for an opera.” The whole structure of that score is very operatic. That’s when I really started to think about the relationship between music and drama in the cinema. It should be of a whole. If you look at this movie “Rob the Mob,” I could actually almost piece it together as if I was composing a symphony. Each theme is very well constructed, the score is well constructed, things return, change come back but in quite an organized fashion. I happen to believe that’s important.

, filmed three times, most recently with Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis.

.