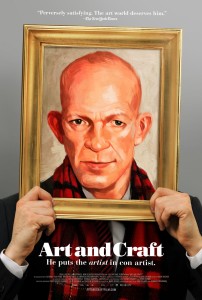

Interviews: “Art and Craft’s” Sam Cullman and Jennifer Grausman

Posted on October 23, 2014 at 8:00 am

The documentary “Art and Craft” is the extraordinary story of two men. One is Mark Landis, an artist who created counterfeit paintings and then disguised himself as various philanthropist personas and donated them to art museums over three decades. The other is Matt Leininger, registrar at the Oklahoma City Museum, who recognized the fraud and pursued clues — and then pursued Landis. I spoke to directors Sam Cullman and Jennifer Grausman about the film, which raises questions of art, ethics, fraud, corruption, mental illness, and how we decide what we value.

How did you meet Mr. Landis?

JG: I read an article in the New York Times in January of 2011 that told the story, mostly from the point of view of Matthew Leininger who had been tracking Landis and that of some of the curators he had donated work to. I pulled the article out and put it in the drawer and was still thinking about it a week later. There were really two stories there. One was the crazy story of a forger who had never sold his work and donated them instead.

I had never heard of anything like that and was so curious about it. Then also the Times sort of described Matthew Leininger as the Javert to Landis’s Jean Valjean and that literary reference really caught my eye as the narrative. I called Matthew Leininger and he was open to coming down. And so Sam and I shot with him until February of 2011 and while we were there, he told us more about the story and we realized we really had to talk to Mark Landis. And so we got in touch with him, originally I think we emailed and then sent him our past movies and then I started talking to him on the phone over the course of several months. And then he invited us down to Mississippi to film him.

Do you think there is a connection between art and mental illness?

JG: It’s interesting. I’m certainly a non-expert so I don’t want to talk about it generally, but I think in this case, Mark has always had this ability for drawing and painting and it is very much a part of his growing up and childhood, working to copy images out of catalogues from museums. It was good for him because there is some sort of comfort when he was alone and also because he was good at it. The art is interesting to him but really it’s been visiting museums and a way to interact with people that’s been really helpful for him. He’s made his own way in the world by doing this and it is sort of an unusual story but it’s his story.

And what we’ve been told by mental health professionals is that it’s been a story that is actually inspiring to them and to other people living with mental illness because he really has found his own place in the world and has not been committing violent crimes and has not been physically hurting other people. And so they find the story to be empowering in that sort of way. For people in the art world – it’s a difficult issue because it portrays bring out issues of authenticity and originality and the importance of that and really what we hope here in terms of artistic intentions.

It’s only the art world that would sort us take a step back and say, “Well, maybe this is his art. Maybe the whole pretence is the art.” It is some kind of a performance art or a conceptual art.

JG: Right. And Mark would not say that, but certainly other people when seeing his story or hearing his story have comments on that. We started the film thinking it was just an art world caper which was what drew us in but I think probably what made all three of us stay interested in the story was meeting Mark and understanding that it was really much broader than this art world framework. You know it really is a portrait of a person, of this unique individual and what he’s searching for.

SC: Mark uses Magic Markers and frames bought from Home Depot and he really has very, very little patience or interest in trying to approximate the actual material used of the era. For him it was really about the art and craft of it all. He says that he doesn’t really consider himself an artist but someone who is just good at arts and crafts.

And why do you think the priest persona was so important to him?

SC: I think Mark has definitely a religious background but I don’t know that it really had much to do with that. I think he describes it as a moment of inspiration. Sometimes he likes to point to the fact that there is like this yarn that every family has got. One child that is great at business and one child is a doctor and you get down to the last kid, and he goes to the church. I think he is tongue in cheek obviously about that but he had often posed as a philanthropist and this idea that a guy from a wealthy family, from the church just felt like a persona that he could be convincing with. I think another inspiration was this TV show called “Father Brown”.

Why did it take so long to bust him? Didn’t the museums ever try to insure these works?

JG: I don’t know actually if they did. I mean there are so many museums and that was over thirty years and there were varying degrees of when museums found out they were fake. Some figured it out right after Mark left their offices and some figured it out six months later, and some didn’t know until Matt Leininger posted on the Registrars list about it. I’m not sure on the specifics.

As you tried to kind of put a narrative around all of the material that you would have put together, what did you see as sort of the through line of the story?

SC: The through line kind of fell into our lap really. It really became the exhibition. There was something that Matt had mentioned in our first interview with him – he described it as a dream, to bring together all of Landis’s known forgeries under one roof and invite him as a guest of honor. We didn’t really know that that was going to come into being and when it did, it became clear that this was going to be the place for the film to end up. We begin with a chase and end up with the meeting of protagonists and the antagonist and you never know which is the antagonist and the protagonist until you get to the end – or maybe you never really know and you’re always asking in your head to figure on your own who’s the villain.

It’s been compared to Jean Valjean and Javert from Les Miserables, but it’s also a little bit like Sherlock Holmes and Moriarty; it depends on whose side you’re on.

SC: Or Tom and Jerry. I think the thing that makes Mark remarkable aside from the most remarkable thing is that he decided never to profit from these fakes. He has this incredible range of what he makes copies of. Typically these master forgers focus on one particular artist or an era. Mark did everything from 15th century icons all the way to modern art, Picasso, and you know, even cartoons. So I think that is pretty remarkable. I think that is a real distinction.

Does he ever create his own art? From his own ideas?

JG: Mark really hasn’t done much of that. He talks about how he went to art school to study photography and he learned all the processes, but then he just didn’t have anything he want to take a picture of. So he does have some original work based on photograph, primarily a portrait of his mother and a Joan of Arc painting. But actually now there is sort of interesting byproducts of a lot of the publicity early on and then the film is that Mark has been approached by some women in his town to do commissions, photographs or paintings based on photographs of their children and grandchildren and occasionally a fake. Also in the course of making the film Mark was also included in this exhibition called Intent to Deceive, this travelling exhibition. The curators helped to create a website for Mark called www.marklandisoriginal.com and so he is now going to able to do commissions.