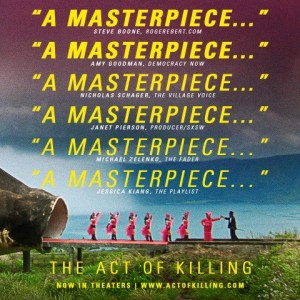

Interview: Joshua Oppenheimer of “The Act of Killing”

Posted on March 1, 2014 at 8:00 am

If I were voting, “The Act of Killing” would not only win the Best Documentary Oscar, it would be a contender for Best Picture as well. Director Joshua Oppenheimer broke through barriers from the secrecy and denial of government-sanctioned gangster killings of more than a million Indonesians in the mid-1960’s to the disaster-fatigue of audiences to tell a riveting story by letting the murders, still living in the community as respected citizens, tell it themselves. The details that have been repressed individually and institutionally for decades are revealed as the men who killed choose iconic movie genres to re-enact their crimes. A musical, a western, a gangster movie — these re-enactments allow both the gangsters and their communities to acknowledge the horrors of the genocide for the first time. The full unabridged version of the film, with scenes not included in the US theatrical release, is now available on iTunes and Amazon.

I spoke to Oppenheimer about the impact that the film has had on Indonesia and the world community and about his biggest regret in making it.

I’m familiar with the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, which sought to provide healing and a sense of justice by documenting the atrocities of apartheid, and it occurred to me that your film is the closest equivalent that Indonesia’s going to get.

You’re right in a sense that before the film came along, there was no chance that the government would implement a truth and reconciliation process. The president of Indonesia from 1999 to 2000, Abdurrahman Wahid also known as Gus Dur proposed a truth and reconciliation process and apology for what happened in 1965 and he was immediately removed from power as a result. But it is also my hope that the film has now opened a space where ordinary Indonesians are saying, “This is wrong” where the media is saying, “This is wrong and we have to talk about this not only to right a major historical wrong, not only for the sake of healing but also so that we can beat corruption, fear, and gangsterism that prevent Indonesia from acknowledging what happened. It’s led the Indonesian media to finally address what had been a 50 years silence about the genocide and talk about the genocide as a genocide and connect the moral catastrophe of the genocide with a moral catastrophe of the regime that the killers have built and presided over ever since. And it’s emboldened ordinary Indonesians to finally talk about the most painful aspect of Indonesian history and the present for the first time without fear. It particularly has led Indonesians to say that “We want this country to be the democracy that we would like and that claims to be. We need to address not just the crimes of the past but also how they have terrorized all of us into not holding our leaders into account for corruption and gangsterism in the present.” So it’s lead to this national discussion which I’m optimistic will eventually be the truth and reconciliation process in Indonesia.

As you spoke to these admitted killers who seem to feel no regret, did you conclude that they had to be sociopaths before they killed the first person? Or were they made sociopathic or numb through just the incredible level of atrocity they perpetrated?

As you spoke to these admitted killers who seem to feel no regret, did you conclude that they had to be sociopaths before they killed the first person? Or were they made sociopathic or numb through just the incredible level of atrocity they perpetrated?

Hannah Arendt famously said in her writings in the banality of evil that the killer is an ordinary person. That doesn’t necessarily mean that every ordinary person is a potential killer. But those of us who haven’t killed are extremely fortunate not to have to find out. My belief is that there is a moral paradigm that underpins most of the stories we tell, particularly in movies where we divide the world into good guys and bad guys. According to that paradigm, we tend to believe that because the killer has done something monstrous, the killers are monsters. And in that sense, we imagine that we’re somehow different from them. What’s clear is that the killers are human and if we want to have any chance of understanding how human beings do this and then the consequences of their actions, how they tell stories to justify their actions, we have to start from the premise that they’re human and that killing changes them. So I think that certainly the numbness comes from having killed. And then because the killers are human, consequently they have to tell themselves stories to justify their actions so that they can live with themselves afterwards. And then horribly, they impose those stories in the form of victorious history glorifying what they’ve done on their whole society. Ironically, that of course leads to a downward spiral into further evil and corruption. If Anwar was to refuse the second time, it’s equivalent to admitting it was wrong the first time.

So further evil is perpetrated not necessarily because the men are monsters but because they’re human and they know what they’ve done is wrong and they don’t have the courage to face that. So denial has a terrible, terrible cost.

There are so many chilling moments in the movie but, for me, one of the most is the talk show where you see the host speak so cheerfully about the killings. Denial is so pervasive throughout the entire culture.

I want to also point out that the talk show is as shocking to Indonesians as it is to outsiders. I think that when Indonesian State Television discovered that the governor of the province or the publisher of the leading newspaper in the province or the head of the paramilitary movement the minister of youth and sport, Anwar who’s famous in North Sumatra — that all of these people were making film scenes, quite ambitious scenes dramatizing what they’ve done, they started to think perhaps we’ve been too tolerant about the killings. You see the history that talks about the extermination of the communists in general terms as something heroic without ever going into the details of the killings. When the producers at state television saw that they were going into the details of the killings rather than say, “Oh, wait a moment, maybe these executioners are getting a little carried away and this could make Indonesia look bad,” they thought instead, “maybe we have been too cautious in our representation of what happened and this is a great story, this is a big story, these are the most powerful people in this part of Indonesia, let’s make a talk show about what they’re doing.” And it sounds more like the individual perpetrators more than it sounds like the mouthpiece of the state which is what State Television is. And it’s shocking for ordinary Indonesians. That talk show is an unmasking of the regime by precisely the institution that until now had served to mask the regime. I guess one other interesting thing is that among the only people in the film who seem to see that the true meaning of what these killers did or the people in the control room while they produced that talk show who start commenting and whispering and saying, “How many people must be haunted? How do they sleep at night? They’re greedy. They’ve been stealing all their lives. They must have gone crazy from doing this.” But we have to remember that even if those other people with the same moral perspective that we have, they are also the people who are actually producing that monstrous show.

Another really affecting moment for me was the guy who was smiling when he told the story about how his stepfather was killed. And then, when asked to portray the part of the victim himself, that was not acting, right? He really was sobbing, wasn’t he?

I think it’s real emotion coming out for sure. I mean he’s being exactly what he said he wanted to do. He says that they should stage this story, everybody feeling uncomfortable that suddenly, there’s a survivor in their midst rejects the idea saying it’s too complicated, it would take too long and he responds by saying, “Well we can at least use this story to motivate our acting.” And that’s what he goes on to do.

And it’s of course real trauma because it’s his real story but that scene is the one thing of the film that sometimes I really regret. It’s an error. It’s an error of omission, not commission but it’s an error. When we were shooting in the studio which was where he tells that story, we would shoot with two or three units shooting simultaneously because there were many things happening at once. He doesn’t speak Indonesians, my cinematographer. He didn’t understand the story and I didn’t hear the story until six months after the shoot. When I did hear it, I was mortified because if I heard it, I definitely would have pulled him out. There a principle that there should be no survivors or victims in the film at all, all of the people in the reenactment of the attack on the village, all of the extras are immediate family members of the perpetrators and the paramilitary leaders. So when I heard this story, I thought, “Oh no. I would have pulled him out. I would have taken him aside and said, “Look, you should be behind the camera for the rest of the day and tomorrow.” But when I put the film together, I could see that he had this sort of very painful journey and strange journey through the film because it keeps cropping up during the talk show, he’s acting in the village massacre scene and I wanted to make sure I really understood what was happening there. Why was he there? How did he feel about it? So even though it made me feel guilty, in a way, I called him and his wife answered the phone and said that he’d died 6 months before from complications of untreated diabetes.

I asked her why he was in the film, did he ever talk about it, she said he talked about quite a lot. He thought that it was the one chance in his life he would have to express the horror of what he’d been through, and somehow felt that even though we were making the film with the perpetrators, this would be the right place to do it. In a sense, he correctly interpreted what we were doing and sort of infiltrated the film, I was making this film in collaboration with survivors in the Human Rights Community and in constant dialogue with them and much of my Indonesian crew comes from that community. In a way, that film was an infiltration into the perpetrator’s world. He kind of infiltrated that. And in that sense, he wanted to be there. He went on a mission. He made the film much more powerful for his presence and if I had pulled him out, he would have failed.

But if I could do it all over again knowing what I know, I would have pulled him out. I would have pulled him out again. When you spend so many years looking at what killing means and torture means, the last thing you want to do is somehow be complicit with its currents.

There’s a brief shot where sort of over in the corner, the television’s on with President Obama talking. Tell me a little bit about what you think that moment means in the film.

Yeah, because Obama grew up partly in Indonesia, Indonesians love Obama and see Obama as the kind of Indonesian in the White House. There’s a big hit movie called “Young Obama.” Obama left Indonesia in fact so he says in his book, Dreams from My Father, because his mother was told that the place was haunted and becoming increasingly corrupt because of this recent trauma that has happened. Genocide was casting a shadow and I put it in the film for the same reason that a lot of the American sort of references are in the film. The United States supported, participated in, and then ultimately ignored these genocides.

I would have loved to be able to go into the history of that but so much is unknown. The United States is also not come to terms with this past. All of the CIA job files from that period remain, covert operations in Indonesia, have been classified. The documents that have been released were then immediately reclassified. Luckily, they were made available by National Security Archives in Washington University but they’re heavily redacted, covered with black magic marker. The US should declassify everything about this.

We want to say that Indonesia ought to apologize, issue a formal apology for what happened and implement a process of justice. The US needs to set an example and take leadership I think. We were a part of this. Fifty years is enough time to get comfortable with what we did. It’s too long to not call it genocide. It’s genocide and it’s time that we all accept what happened and our collective role in supporting and participating in those times. And when I found out that Hammond was watching Obama’s inauguration address as a kind of a victory speech to practice for his own speeches, I immediately felt that it implicates all of us. And Hammond says his reason to go into politics is to intimidate people and to steal. And the fact that he’s inspired by Obama somehow evokes the sense that some of it is the unintended or the intended consequences of US policy.

How does the experience of re-enacting these crimes within the context of different film genres make you feel about narrative films? Does it make you change your idea about how influential they were or about a certain moral quandary of making narrative films?

I think that this is a film about how we tell stories to justify our actions to escape from our most bitter and painful truth, and it’s a film about how we lie to ourselves and it’s a film about those consequences for those lies. These characters used cinema at that time to distance themselves from the act of killing, coming out of the cinema inspired by whatever movie he’s just seen, waltzing across the street, dancing across the street, he could be intoxicated by his love of the film especially for example, and killing happily.

Cinema is a means of escape. And this is a film about escapism and the importance also of confronting the most painful truth about who we are and equally in this film, that there’s also I think actually a demonstration of how cinema can equally be a mirror in which we actually look at the most painful aspect of who we are. Cinema becomes the vehicle with Anwar and all of Indonesia now are looking at the most painful aspect of what it means to be who they are. I think the film is kind of a manifesto almost of how art ought to be a means by which we invite to do or force our viewers to confront really the most important, painful, mysterious, troubling aspect of what it means to be human.