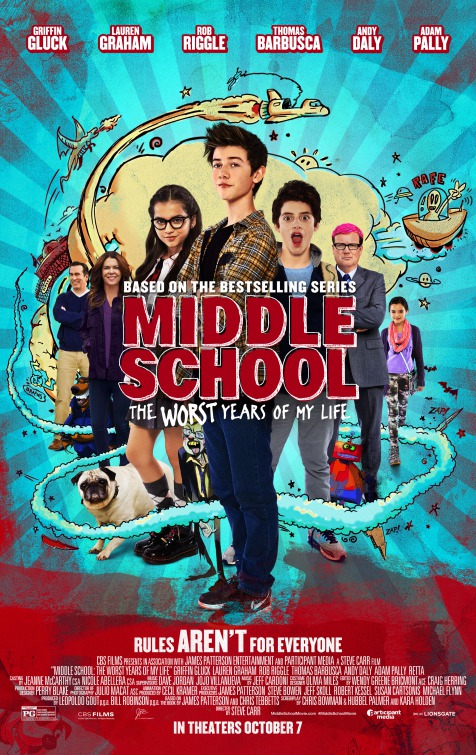

Interview with Kara Holden of “Middle School: The Worst Years of My Life”

Posted on October 14, 2016 at 3:01 pm

Did you ever play any pranks or engage in any rebellions when you were in middle school?

I wish, no. I was definitely goody two shoes for sure but in my head. I had a rich imaginative life much like Rafe but I wasn’t able to act on much of it. So I would write stories or I would write things in my journal about what I wish I could do. And I was never was quite bold enough to go as far as he went which was what was fun about writing this. It’s very much wishful filming.

Of all the pranks in the film, which is the one that you vicariously fantasized the most about doing yourself?

I love the sprinkler one. It’s definitely my favorite. I just love the idea of everyone getting out of class, dancing in the hall. There was something about it that just made everyone loosen up and have fun and have a huge party in the middle of a school. I would love to have that happen. No matter who you are, you are going to love a crazy experience like that.

It’s refreshing that the girl characters in the film are complicated, real characters.

That was incredibly important to me. I did want not want them to be the boilerplate girl character, the annoying sister character. I definitely wanted them to be full of life like the girls that I know and to have that spunk. Actually my niece Jane, not that she is Georgia, but she has a lot of that fun, spunk and spirit. She will stand up for herself and I wanted that message to come across. At the same time there this that tenderness. Georgia is bold and strong but she’s not afraid to show her vulnerability which I think is very important also, that we could be well-rounded. And I love Jeanne, she’s my alter ego of what I wished I could be. She’s smart and she’s cool and I love that she’s the one who runs the audio-visual club, that she was doing the investigating, and she’s tenacious. She had a voice and she wasn’t afraid to use it and I loved that. I just enjoyed writing them both and of course the mom as well. I think that more people need to speak up, boys and girls really to speak up for what they believe is right. And that’s what Rafe did as well, he uses his gift for art to raise awareness of what was right. So that’s great.

The movie has some great comedy and fantasy revenge, but it is grounded in a reality that acknowledges some very real losses and problems.

It was really important to me that all of these characters are grounded in the heart and in a reality that can feel real. Every person, especially kids, we all experience hardship and there are some things that can’t “be fixed.” But we can grow, we can learn from these things and we can move on in a positive direction and I wanted that to really be a part of it. And truly hats off to the actors who were able to play all so well, to do the comedy and the drama, I think that added to it but really the comedy stemmed from the base of the bedrock of the movie, which is a very heartfelt thing. I don’t want to give away any spoilers but I think that was underneath in my head in every scene I knew why the things were happening that were happening and I was grounded in character and that is I think what makes it work. If the humour comes from the character, from where they are and not just on top of a bunch of jokes, then it’s going to feel cohesive when you move from comedy to drama.

Leo is a wonderful character, too.

I mean I’m amazed by all of them I think they all did incredible work but Leo gives Rafe the confidence that he needs to pull off these things. Leo believes in him so Rafe discovers and learns to believe in himself. I think the fact that Leo has good intentions in all that he does is what makes him so great. He is a hellraiser for good. So I think that’s what makes him so likable and that’s why you care about him and the relationship between Leo and Rafe. It feels real and you root for them. I think it’s important that we see that they are there for each other.

Tell me about your writing day. What’s the first thing that you do when you wake up in the morning?

The first thing I do is, I go in and I wake up my son, he’s a year and a half. I don’t wake him, he usually wakes me up. I hear him in his room, and I can take care of him and I take care of my animals and then I get ready and I go to an office outside of my house. Actually before I leave I do a little bit of my emailing and things because I don’t have Wi-Fi at my office on purpose. It’s the most perfect place. It has no windows. It’s just a room with a desk and a computer and I have to work and that’s good for me because like most writers I’m very procrastination-prone. Once I get to my office it’s all good.

You’ve worked in a variety of genres. As a writer, how do you locate the audience in the world they will be entering?

That’s a good question because for me pretty much the connecting fibre from all of the films I’ve done, whether it be inspirational sports or more of a drama or is also a comedy and a drama as well, is that they all have humor hopefully and heart. I try to do that in all of them even though they are in different genres from family to more adult or the inspirational world. I try and get the characters up front. With “Middle School” I immediately had the idea that I wanted to just get into how much his art meant to him and having that fun little animation bit at the beginning clued us in that this is going to be fun and a little bit of a wishful film and have some fantasy right on the very first page. You just set it up from the get-go what you are in store for by some sort of a visual or an action that a character is taking that you recognize as either funny or more serious. In a comedy it feels good to get a surprise, to switch things up a little, to give you something serious. Sometimes you just need a break in a drama so it feels good to laugh. And by the way that’s life. It’s a great combination — comedy and sentimentality and difficulty all mixed up. So I like to have something sort of heightened but the reflection of life so we can recognize ourselves in it when we see it and that’s what makes us love it.