Interview: Kelly MacDonald and Marc Turtletaub of “Puzzle”

Posted on August 7, 2018 at 8:00 am

In the midst of the summer blockbuster season, a quiet film about a neglected wife who does jigsaw puzzles is getting a warm reception from critics and fans, with special praise for an exquisite performance by Kelly MacDonald as Agnes in her first lead role. I spoke to MacDonald and director Marc Turtletaub about the film.

There’s a timeless quality at the beginning of the movie as we see Agnes getting the house ready for a birthday party. We don’t know if it is set in the past or just today in a place that has not changed very much over the decades. It’s a surprise when one of her gifts is an iPhone because until that moment it could have been taking place in the 1950’s or 60’s.

Marc Turtletaub: Yes, it was intentional. You do it in the production design and the cinematography. Those early scenes are shot in silhouette and there is a lot of smoke being blown into the room by the cinematographer. It creates an atmosphere in which it feels almost like Agnes, the central character, is stuck in time, and she is as a character. She’s in the house she was raised in, in the house where she took care of her father, the one she raised her children in and so we wanted to create a sense in the environment that it was almost from another era.

It’s not only in the cinematography but it’s the production design and the costume. I spent way too much time picking out a dress for Agnes that would meld into the wallpaper we were picking out so you’d get the sense that not only was she stuck in time but that she was almost unseen in part of the environment.

Kelly MacDonald: There is a book, The Yellow Wallpaper, and that’s exactly what happens to her as she disappears into the walls.

MT: And in Garden State where it’s a complete match. We didn’t want to go that far. We did have a reference though, Bonnard. I was at a museum and I saw some of his work and I was so taken with how the study had a woman in front of the background and they melded so perfectly I went, “ That’s it, that’s what I’m looking for.”

Kelly, you had an unusual opportunity and challenge because you created the character without any words for the first part of the movie.

KM: I’ve always been interested in what it would be like to be in the silent era like Lillian Gish and just solely rely on expressions. So this was like my opportunity. I hadn’t realized when I read the script quite how much of the film has Agnes on her own. I just find those scenes were quite lonely because I got used to being around boys and family and everything and so there was a bit of that but I did quite enjoy just being able to express things without words. Quite often I’m trying to get rid of extraneous dialogue anyway. I’m happy without words.

Your character solves the puzzles very quickly. How did you make that look so natural?

KM: It brought back how much I like puzzles. So I was doing them when I would finish work for the day. I stole a couple from work and I would go back and decompress by doing puzzles. It’s very Zen and relaxing.

And I’d be presented with the prop of the day puzzle and then I would start to find a spot and take the best side that I wanted to work on and then place them on the table and try and remember where I put the pieces I’d be using. It was good brain training. And then I would start do it as fast as possible.

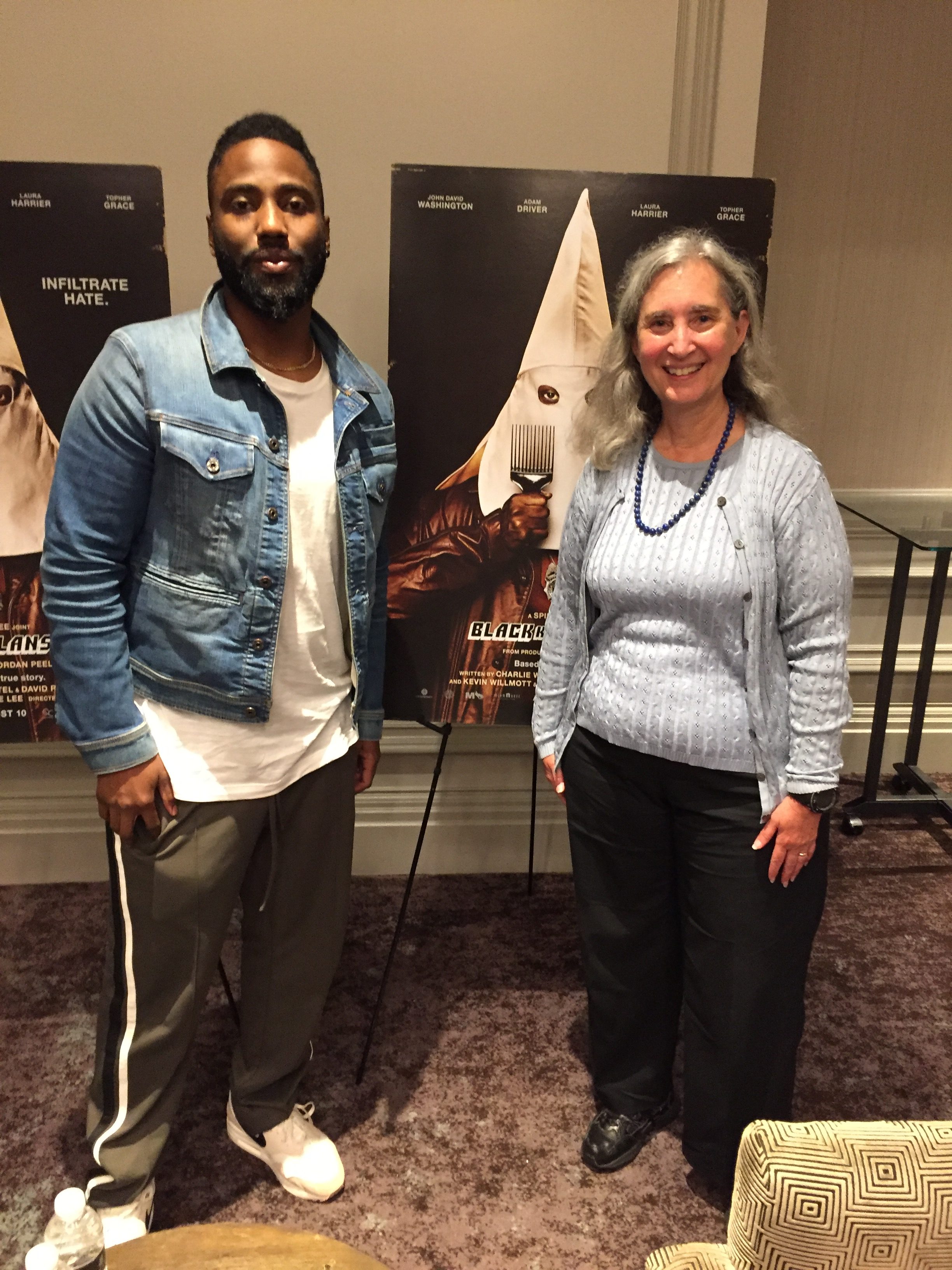

You were acting with one of my absolute favorites Irrfan Khan. Did you consult one another on the chemistry between your characters?

KM: I don’t think we really did discuss it. It was just suddenly he arrived as a fully fledged oddball. The first scene we filmed together was when I tell him I know he is an inventor. That was a good introductory scene to do actually because it was quite a long scene and we got to be face to face. I got to be awkward and he got to be just sort of bemused by this strange woman. When I think of him in the film I think of him in that doorway just being so physical and brilliant and just compelling I think.

There are a number of literal reflections in the film. What does that, well, reflect?

MT: I think of one that probably stands out most of all to me and it’s about it’s the moment where Irrfan Khan’s character Robert talks to Agnes about how active her mind is and the fact that she has nowhere to express it, no one to express it t. He sort of nails it and says something to her that no one has ever said to her but at the same token he actually listens to her. He can be a bit of a mansplainer but he also sees her in a way that maybe no one except her eldest son somewhat sees her.

There’s this wonderful moment after that where we hear Ave Maria and then she walks off and she goes down the street and we set it up so that as Kelly walks you see her reflection in the windows of the stores. And then she stops in front of one store and she flips her hair up and she puts it on top of her head and she pulls it behind her ear. As soon as I read it, that’s the visual I had in my mind. I wanted to see her looking at herself maybe for the first time in years as a woman and thinking about being more self-conscious.

We wanted to show different images (I call them portraits) of her at different stages of the movie and some were more successful than others; that was a successful one. I think another successful one is some of the reflections in the train and we just tried to capture Agnes at a different point in time to see how she’s evolved during the course of the movie.

Marc, You have an unusual career path for a director. What does being a CEO teach you that helps you as a director?

MT: I’ve had a strange life, not just career and I’ve had a lot of experience in a lot of different things. What I think I’ve learned as I’ve gotten older is how to collaborate. People who are leaders in whatever endeavor and become successful over a long-term learn how to encourage other people. That’s something you do as a director. You encourage others, whether you’re a parent doing that and leading your children or whether you’re running a company, you’re encouraging. You hold a vision, you know how to set a boundary when you need to but there’s so much about encouraging people to do their best. And when you have people like Kelly and (I really say this in all candor) and Irrfan and David Denman and the young people we had, it makes the job really easy.

I love the way that recognizing her gift for puzzles inspires Agnes to notice more of what is going on around her. She even tells her husband she thinks they should begin watching the news. And she notices for the first time how unhappy her son is.

KM: It isn’t that film about a sort of savant which is great. She’s good at puzzles and she is fast but it’s not the through line of the film. What it does is remind her that she used to really quite like math. It just starts this little thing inside her brain, like this little scratch, and she wants to know what life might have been if things had been just even slightly different.

I just love that. The thing I love about her is she’s kind of got Truth Tourette’s — she just says what’s in her head. She does lie in the film but she does quite a bad job of it and struggles. But when she’s relaxed she can’t help but just see and some things that she says are totally brutal.

She’s a grown woman but she’s like a child. She is being kept like a sort of child-woman and it’s quite right that she has to at some point start discovering herself.

And her oldest son completely sees his mother and what she is and who she is in a way that Agnes isn’t even aware of. but he hasn’t spoken about it and it’s when she starts to sort of change slightly in these tiny ways to normal people but to her family it’s just seismic and it’s the tremors, the after-effects that touches them all. It’s really a beautiful thing that as she’s beginning to sort of open that door inside herself.

When you’re so trapped inside yourself it’s hard to see anyone else. If you do not see yourself with any depth how can you see depth in other people? This experience gives her the ability to just recognize her son’s in real trouble and she’s a very good mom and I think it’s lovely.

MT: She frees him.

KM: And it’s not a romance film either. It’s not about who is she going to end up with, who is going to make her better because it’s her journey. She could have fallen into either set of strong arms and the problems would remain and she would still have a lot of work to do on herself.

Marc, as I look back on the movies you have produced, it seems they are all about imperfect people trying to do the best they can.

MT: I try to. That’s like all of us, right? Audiences are hungry for real people realistically displayed. Mike Leigh said it beautifully: He takes the mundane and makes it poetic. That’s what we aspire for in this movie, to have ordinary characters but their lives stand for something so much bigger.

KM: Ordinary stories that move you, When people talk to us about how this movie makes them feel, they touch their hearts, literally put their hands on their chests, and I love that.