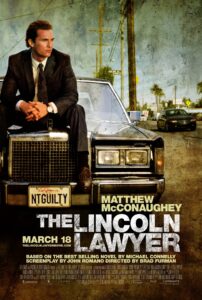

Interview: Michael Connelly of ‘The Lincoln Lawyer’

Posted on March 16, 2011 at 8:00 am

Michael Connelly is a journalist-turned novelist whose enormously successful crime stories have filled 18 novels, translated into 13 languages. This week’s release, “The Lincoln Lawyer,” starring Matthew McConaughey as defense lawyer Mick Haller, Marisa Tomei as his prosecuting attorney ex-wife, and Ryan Phillippe as his wealthy client accused of murder, is based on his book. That’s “Lincoln” as in town car, not President, by the way.

How did what you learned as a journalist help you as a novelist?

A lot of what I did has a journalist has carried over into the books. The key has been the observation skills, to watch things and look for details to flesh out the picture. And when you’re a journalist you never have enough room. So you look for the telling details, instead of fifty, you have to find one to open up a window in people’s imagination and understanding. You listen for the dialogue that is more than fluff that actually carries information. Those are all day in, day out practices of journalism. Even though I’ve shifted to the kind of canvas where I can write unlimited pages and words I still follow the journalistic style. It doesn’t matter if it’s 400 pages. What matters is that there is momentum on every page. Shorter sentences that carry import in every sentence is the way to go.

Your main character is called the Lincoln lawyer because his office is in a Lincoln town car that he rides in from court to court and client to client. Is there really a Lincoln lawyer?

He’s retired now, but this whole project, book and movie, began about ten years ago next month, when I went to the first game of the year for the LA Dodgers, the home opener. I was invited by a friend and sat next to another one of his friends, whom I’d never met. During the course of the game there, it was “Who are you, what you do?” I had covered the courts in LA and I knew that if he told me where his office was, I could tell what kind of work he did. The courts in LA are all over, Century City, the Valley. That’s when he said, “It’s actually my car.”

He was very quick to say, “That’s not because I’m a bad attorney or not successful; I live in Malibu. It’s because it’s the best way of taking this city, with 40 courthouses, and I have a guy driving my car who is working off his legal fees.” By the 9th inning I had what I was sure was an idea that could go the distance. I get lots of ideas, but I really need one where I can spend a year with this character, where I can find 400 pages of a story about him. It happened to be when I was looking for a new character to write about. I had a lot of books about a detective and wanted to go to the other side and write about an attorney. And I knew this was what I was looking for.

He was a stranger to me. He gave me the idea with his lifestyle, but then it happened I was moving away, back to where I’m from in Florida. I reconnected with a guy I had known since college there, who was a criminal defense attorney. I told him I needed to know the nuts and bolts of what his job was like. On and off for three years I shadowed him and his partner, drank with them after work, had lunch with them, went to jail, went to court. And there was a judge who let me sit in her courtroom, follow her into chambers, see how she ran her courtroom.

I like the story’s contrast between the theory of justice and the reality. Your main character is not easily categorized. He’s very moral within his own construct.

One of the things that impressed me in the people that I worked with was the stuggle between the idealism of our justice system, the idea that that no matter how bad the crime, you’re entitled to the most vigorous defense. But you try practicing that, sitting all day next to a child molester or worse, it’s very hard to do. There’s lot of alcohol in the movie, but that’s the reality that I saw. The best research for this book occurred at 4:30 in the afternoon, when the courts are done for the day and everyone stops for a martini on the way home.

I could spend my day writing and then go to these two bars, and that’s where the real gems of this book came from. That’s where the line that’s in the book and the movie comes from: “There’s no client as scary as an innocent man.”

It’s that struggle between the idealism and the reality that has affected Mickey, and we get to see what that has done to him. I love in the movie how his investigator played by William H. Macy is telling him what he has to do in legal terms and he just cuts him off, saying, “I’ve just got to make it right.” That’s the crux of the story, that he feels he has to make it right.

Tell me how you go about creating a believable villain.

The villains are always the easiest because you don’t have bounds. They can be, as displayed in this movie, so convincingly sane and innocent and then be just the opposite. One of the things I love about this movie is the way it respects the viewer. It doesn’t try to hide who the villain is. The intrigue, the real story, is how Micky is going to get out of the trick bag he’s got into as he calls it.

The villains are the easiest people to write about — you get a certain amount of freedom to make villains smarter in fiction than they are in real life. You start with the idea that they have broken free of any societal restrictions and then you can layer on all kinds of stuff, camouflage and all that stuff. They’re fun!

I’d like to know something about adapting a book for a movie. To begin with, a screenplay is much shorter than a book.

I haven’t had a great history in Hollywood. I’ve sold ten or eleven books to be made into movies but this is only the second one to be filmed. They break down because of the scripts. The books live inside characters’ heads and scripts can’t. I’ve learned my lesson; that’s not my skill. I like to tell readers what the characters are thinking. I was very careful about who I gave this book to. It was almost like an interview process. I was at a stage of my life where I wasn’t worried about how much they were going to pay me. I just wanted to know how they were going to keep the integrity of the story. I talked to big studios, little independents, one actor who wanted to do it. But Tom Rosenberg of Lakeshore had been a trial attorney in Chicago. So he said, “This is a world I once inhabited. I know it and you got it right. I promise if you let me make it, the gritty realism will be preserved. It will be in the movie, I can guarantee you that.”

They went through about 14 drafts. It went from one where I thought it was missing stuff to one where I thought, “This is the book, this is the character.” Matthew McConaughey is not like the character in the book who is half-Mexican and described as very dark but with a name that did not indicate his background. He had lots of contradictions to add up to his feeling more like an outsider. I heard McConaughey had signed on. When I saw him as the sleazy agent in “Tropic Thunder” I leaned over to my wife and said, “He’d make a good Mickey Haller. And months later, maybe a year later, I heard he wanted to do it and wanted to meet me and talk about it. He spent a year studying and preparing. It was very impressive. So it doesn’t matter how he’s described in the book. He’s that guy. He totally owns it.

I liked the way you make Mickey defy our expectations in both his personal and professional lives.

There are now three more books with him as a character. Defense attorneys are generally misunderstood and blamed. People despise them because they think they’re trying to get the scum of the earth out of jail. Most of the time I write about a detective and it’s very easy because everyone is already on his side — you want the murderer to be caught. Maybe this is why I waited to my 15th book — I felt confident to take on a character most people would not like if not despise, and somehow make people want to like him and ride in that car with him. I was going to make him really good at gaming the system, even if it was going to be toward a goal people might think was negative, you couldn’t help but respect that. And the other aspect was I wanted him to have that higher moral code that would come out in the story. I’d want to hit them with the skills right away and then slowly bring out the moral code. In the book I enjoyed tricking the reader with Mickey talking about his office without revealing that his office is his car. In a visual medium like a movie, that’s not a trick you can pull.

Why do people like mysteries so much?

They’re stories where there are high stakes. Many of these people if they’re not stopped, they’ll do it again. We like to read these stories because it’s about people making a difficult choice to do the right thing, even though it could endanger them or their families, and we all want to know what we would do. Reading stories like that give us our ideas about how we could be.