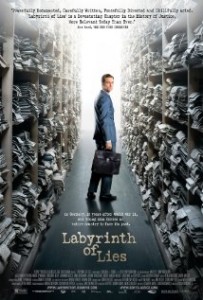

Interview: Giulio Ricciarelli of Holocaust Drama “Labyrinth of Lies”

Posted on October 1, 2015 at 3:43 pm

Giulio Ricciarelli co-wrote and directed the German film “Labyrinth of Lies,” based on the real-life story of the courageous post-WWII German prosecutors who insisted on investigating the atrocities of the concentration camps and prosecuting those responsible. Surrounded by former Axis and Allies officials who wanted to put the past behind them and move on to fighting the communists. He talked to me about the inspiration for the film, what really happens to the movie’s couple after the ambiguous ending, and why the owners of the vintage cars used in the film drove him crazy.

The movie’s opening takes us into a world almost impossible to imagine, where concentration camp survivors are living with the people who imprisoned and abused them and the world has almost no information about what would later come to be called the Holocaust. An artist is offered a light by a teacher watching some children in a school playground. When he bends over to reach the flame, he sees the teacher’s hand and recognizes him as a former Nazi. “That symbolized the theme of the movie, the tormented meeting the tormenter. And the second thing that was important that I wanted it to be a teacher because if you imagine him teaching children that is so horrible and that’s something that actually happened a lot. And so we had these two elements and I knew that as a filmmaker I needed a point of seeming harmony in perfect world, an innocent world. A school is like that. So it was important, the tree and the school and the children playing. And then the movie starts and you realize there is something very wrong there and so it was important to have this. There is a German word that means like a mix of sane and beautiful. It’s like an untouched world.”

The “big complex task” of the film was making what is very familiar to us unfamiliar, so we could feel the shock and horror of the young Germans who came of age after the war and did not know about the “Final Solution.” The movie’s main character is fictional, a young lawyer working as a prosecutor, though some of the other characters are based on historical figures. “That‘s why we choose this young naïve main character, hoping that we enter his world, we start looking through his eyes and the reaction I get is great. It seems to be working with go back in time and go with it. The other thing is esthetically of course; first of all you got to plot what you just mentioned.” The very pervasiveness of the portrayal of the Holocaust created a separate challenge as well. It is so well known that it is impossible to replicate in a persuasive way. The audience at some level always knows it is a re-creation. “The audience can almost hear the director say, ‘Okay lunch.’ And you see actors who are well fed. So I said, ‘Okay, we will not have any of that. We’ll not even have testimony like an actor acting as if he was in a camp and we will trust that these iconic images will come when we give them room to come and the audience.” And so, when the scene comes where a survivor provides testimony for the first time to the lawyers, we do not see or hear him. We just see the reaction of the woman taking dictation, and we feel we know what she heard and saw.

One reason for the film was to recognize the courage of the lawyers who insisted on the truth. But just as important was showing that the only way to move forward after unthinkable inhumanity is to completely honest about it. “In Germany, anything we do politically or culturally is seen through that lens, that’s the reality and if you are talking about refugees if you are talking about Greece, if we talking about anything it’s all we see in the frame of this. The country who did that now does this. The thing is, you cannot deny it, that’s not the way, and you can’t leave it behind.” One way to do that is what he did here, finding a new way to tell the story by looking at a part that has not been told.

“I think what is important with our film is that it’s a not told story. I think what is most important is the movie doesn’t pull any punches when it comes to the involvement of Germany as a whole because there is sometimes a tendency to show two evil Nazis and the rest of the population is confused. That’s not historical fact but at the same time not to sit on a moral high horse. That’s why the main character says, ‘I do not know what I would done.’ And if you look at the atrocities not just in Germany but all over the world the human beings are usually not heroes but they go along and they do the easy thing and they don’t risk their own lives and there are heroes but they are few and far between.” He described the continual presence of this history in Germany as an iceberg. “Under the waterline it’s still huge and it’s still usually influential in Germany, it’s certainly the biggest influence in German politics and culture today.” Everyone in Germany was supportive of the film and cooperative in helping to get it made, including Frankfort, where they filmed on location at the places where the events actually happened. One of the most striking images is the rows and rows of documents. The real archive no longer exists in that form, but they found another storage facility with old documents and used camera angles to make it look biggers.

But one challenge they faced was the vintage cars they needed for the shoot. “First of all they are very expensive, but you know what the biggest problem is? They are owned by collectors, so in the morning you always get that spit shine car and they would say, ‘Don’t dirty it up,’ but we have to spray dust over it and sprinkle it with dust and tell them to bring it back dirty but the next day it’s clean again.”

He has been very moved by the response to the film from people who still struggle with the truth of what happened. “And how much rawness there still is. Like a woman came to me and said, ‘We have a box from our grandfather and our family and it’s closed as we are all afraid to open it, because we don’t want to know how grandpa died in the war.’ Or the man who shook my hand and said, ‘Thank you for this film,’ and then he went five steps and he came back and he looked me straight in the eyes and he said very quietly, ‘My father was a bad man.'”

The movie ends on a positive note about the prosecution of those responsible for wartime atrocities, including cooperation with the Mossad agents who tracked down Adolf Eichmann. But it is ambiguous when it comes to the future of the couple in the film. I pressed Ricciarelli to tell me what he thought would happen to them after the movie. He told me he shot two endings but went with the one he thought was more realistic. Still, he smiled and admitted “there is a ray of hope.”