The Highwaymen

Posted on March 21, 2019 at 5:12 pm

B| Lowest Recommended Age: | Mature High Schooler |

| MPAA Rating: | Rated R for some strong violence and bloody images |

| Profanity: | Some mild language |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Drinking and alcohol abuse |

| Violence/ Scariness: | Extended bloody violence, characters injured and killed |

| Diversity Issues: | None |

| Date Released to Theaters: | March 22, 2019 |

“The Highwaymen” is the un-glamorous story of former Texas Rangers called back into service who persevere despite unreliable politicians, incompetent federal agents, and a population, including criminals and Depression-era fan who were on the side of anyone who was not on the side of the banks. The story of the lovers who defied the rules created by the rich and powerful and shared cheeky photos of themselves holding guns was much more appealing than the idea of bringing them to justice.

Director John Lee Hancock “The Blind Side” and writer John Fusco (“Young Guns,” “The Shack”), are, like the story’s lead characters, disgusted with those who think that Bonnie and Clyde are more appealing than the men who caught and killed them, though that does not prevent them from altering some of the facts themselves.

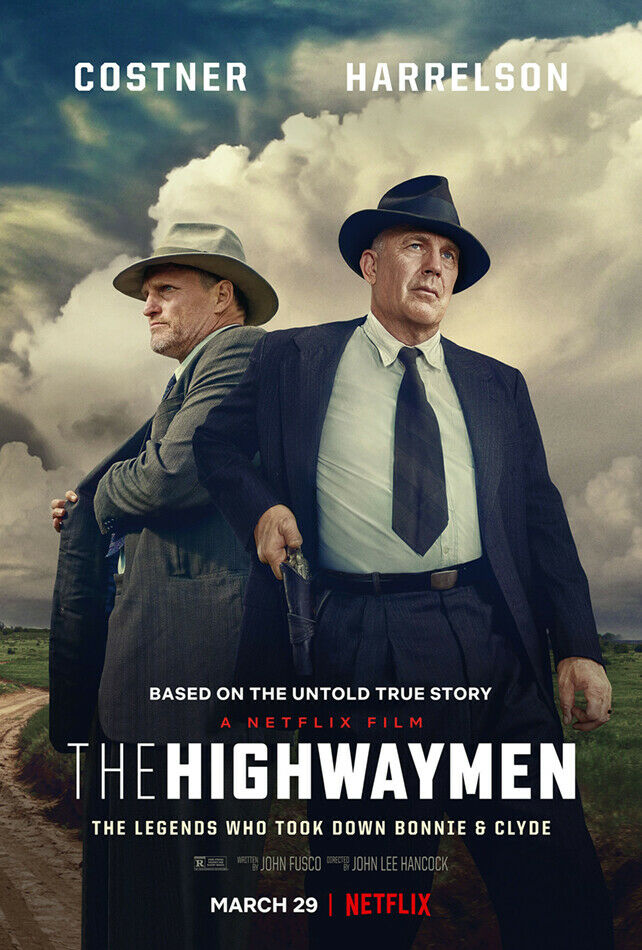

The focus here is on the two old pros, Frank Hamer (Kevin Costner) and Maney Gault (Woody Harrelson). In the Penn film, the Hamer character was portrayed as hapless in comparison to the people he was tracking, initially captured by them (which never really happened). In this version, we only catch brief glimpses of the notorious duo. It is clear who we are supposed to respect and root for.

Texas governor Ma Ferguson (a deliciously bellicose Kathy Bates) has shut down the Texas Rangers in favor of a more modern form of law enforcement. But when it comes to the crime spree of Bonnie and Clyde, she recognizes that she doesn’t need modern and she doesn’t want law enforcement. She wants them dead. And so she has someone contact Hamer, now a successful private investigator living comfortably with his wife (Kim Dickens). And Hamer contacts Gault, living in near-poverty with his daughter trying to stay off the booze.

The pace of the film is slow and deliberate because what these men are doing is slow and deliberate. The filmmaking is straightforward but thoughtful. A scene where Hamer and Gault search what turns out to be an empty house is especially skillful, with the lawmen framed in a dresser-top mirror. The images of Depression-era life, the campout of what in those days were called hoboes, the saucy red shoe that is all we see of Bonnie in her first appearance, the stop to buy guns and the boys who help Hamer with some secret target practice, the face of Hamer’s wife (an excellent Kim Dickens) as she says goodbye — all reward the patient viewer.

Costner and Harrelson have the kind of easy chemistry that suits their characters, men who have seen too much and done too much. They know they have done wrong in the cause of right, but they also know that their wrongs kept people safe. They know that they will not be appreciated by the politicians who will claim credit for their successes and blame them for mistakes made by others, or by the people who thought of Bonnie and Clyde as a romantic fantasy of living fast, dying young, and leaving a good-looking corpse, if you don’t count the bullet holes. But that knowledge will not, as anything else can not, turn them away from what they see is their duty. This movie does what they were too proud to do themselves, tell their story and let us learn from it.

Parents should know that this is a crime and law enforcement story with extended peril and violence. Characters are injured and killed and there are some graphic and disturbing images. The film also has some sexual references, some potty humor, alcohol and alcoholism, and some strong language.

Family discussion: Why did Hamer and Gault take the job? Why did Clyde’s father want to talk to Hammer? Why did so many people root for Bonnie and Clyde?

If you like this, try: “The Untouchables” and “Bonnie and Clyde”