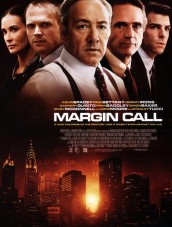

J.C. Chandor wrote and directed “Margin Call,” a sharply-scripted thriller about one night at a never-named Wall Street firm. The top executives discover that they are at risk of catastrophic failure and have to decide before the markets open in the morning whether they or their clients will take the losses. The movie stars Jeremy Irons, Keven Spacey, co-producer Zachary Quinto, Stanley Tucci, and Demi Moore. It is specific enough to make some very pointed commentary on the financial meltdown but universal enough that its themes of betrayal and externalized costs could be set in any industry or indeed in any organization.

J.C. Chandor wrote and directed “Margin Call,” a sharply-scripted thriller about one night at a never-named Wall Street firm. The top executives discover that they are at risk of catastrophic failure and have to decide before the markets open in the morning whether they or their clients will take the losses. The movie stars Jeremy Irons, Keven Spacey, co-producer Zachary Quinto, Stanley Tucci, and Demi Moore. It is specific enough to make some very pointed commentary on the financial meltdown but universal enough that its themes of betrayal and externalized costs could be set in any industry or indeed in any organization.

How did you come to write about the financial meltdown?

I had written several different things in several different capacities but had never done anything even sort of remotely topical let alone completely topical. This was being written for myself to direct so it was from a very personal place, not a Hollywood script to go out and sell. A lot of what has become the strength of the project and drew people to it came from an odd place, from production restraints I placed on myself to keep the budget realistic.

I’m a total real estate junkie and took time off to set up a partnership to renovate an old building and it happened to be on the other side of the real estate bubble. The godfather of one of my partners was a very prominent investment banker, a ground-breaker, an intellectual, invented the concept of a real estate hedge fund, a whole new model. He intervened in his godson’s life and about halfway through our project came to him and said, “Those offers you’ve been getting to buy the project half-completed — take them. I’ve been leaving millions of dollars in deposits on the table because it is time to get out.” We took his advice, mostly because we were having trouble with one of the other partners but also because we had the feeling things were not going well in the markets. We just broke even and felt like a defeat at the time but a year and a half later I felt I had a new lease on life.

As things really started bubbling to the surface I thought back to that man and what it was like to be walking around — you never know for sure, but he felt pretty strongly things were bad enough that he had to take a financial hit to avoid a worse one and warn us. I thought it was an interesting issue to look at it from the inside, and do a small character-driven story about investment bankers as they see what they thought their lives were about changing in a deep way and what their responsibility was, all those things that were a little bit unsaid in the film but that the actors and I knew were all there. I have only so much time, so much energy, this skill set, and this is what I’ve used it for.

It has the setting of a drama but it feels like a thriller.

To be there on that day was an interesting limited view into a wide problem. It’s a ticking time bomb structure, which is a thriller by its very nature. The one total deviation is that 45 minutes into the movie you know the bomb can’t be defused. The drama is who will they hand the bomb to?

Do you see them as villains?

What most people would choose to do in this scenario is what these characters do — to look out for themselves. To look at it in the macro viewpoint, they made the decision when they walked into the door coming out of Harvard or wherever they were to use their time and skills and very intense intelligence and education and have the big majority of those people get siphoned off into this world. People who have already made that choice when they walk in the door it is unrealistic to expect them five, ten, fifteen years later to make a different choice about who to take care of.

Your father worked on Wall Street, at Merrill Lynch. Did he guide you at all on the script?

For superstitious reasons I didn’t show the script to anyone in my family. I’ve had a lot of false starts if you know what I mean! I didn’t really tell my family I was doing this until we were really at the point of no return. But what I learned from my father and from friends over the years is the toll that it takes on the people who stay behind and keep their jobs when others are let go. It’s one of the only businesses that even in their best years still culls 5-10 percent of the workforce every year purely for motivation. The people who last are the ones who play the game correctly. For certain characters like Spacey’s it’s not about greed; it’s about survival. For others like Simon Baker’s and Demi Moore’s it is about ego and the way you define yourself.

I originally wrote the scene when it wasn’t the big dramatic day, yet. It was supposed to be more run of the mill, but as things developed in real life by the time we shot it, it became too subtle.

The way it was revised though, gets Stanley Tucci’s character out of the building, and that is important for the plot.

The fun thing about Stanley’s character, Eric Dale, is that I have a hard time naming characters and I usually use names from people in my life. Eric Dale just worked and it is amusing for him because every character says the name through the film as he becomes the symbol of the paranoia that the information will get out.

I won’t give it away, but I wanted to tell you how much I liked your ending — you took something of a risk and it paid off.

The ending and the music are the things most people feel comfortable having an opinion about. For me, the movie started with the ending and then you figure out how you get there. Kevin Spacey would say something different but for me the most important thing is what’s behind him, the house. It became very important to understand that in his mind, he did need the money. No matter what you make, the way people rationalize their connection with money is almost identical. As Paul Bettany says in the film, “You learn to spend what’s in your pocket.”