“Oh God, thy sea is so great and my boat is so small.”

“Oh God, thy sea is so great and my boat is so small.”

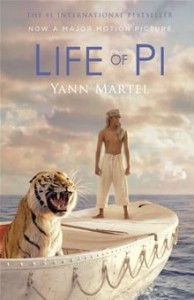

This classic Breton fisherman’s prayer describes “Life of Pi,” Ang Lee’s exquisitely beautiful fairy tale story of an Indian boy shipwrecked with a Bengal tiger, and their journey home.

The book by Yann Martel is an award-winning national best-seller, filled with meditations on life, faith, and zoos. Pi, played as an adult by Irrfan Kahn and as a teenager by newcomer Suraj Sharma, was named Piscine Molitor after a swimming pool in France. He insisted on shortening it to Pi after the kids at school teased him, and showed off by memorizing pi to the hundreds of places. Pi’s family owned a zoo in Pondicherry, India, or, rather, the community owned the zoo and his family owned the animals. When they must leave India, his parents sell most of the animals and pack up the rest with Pi and his older brother to travel to Canada by ship. On a stormy night, the ship sinks and, according to the story the adult Pi tells to a visitor, the only survivors are Pi, a zebra with a broken leg, a hyena, an orangutang named Orange Juice, and a Bengal tiger improbably named Richard Parker thanks to a clerical error and always referred to by his full name. Soon, it is just Pi and the tiger.

Pi is an unusually thoughtful boy who considers himself at the same time a Hindu, a Moslem, and a Christian. (This is described in much more detail in the book, including an amusing encounter between two of his teachers.) His parents are not religious and his father jokes that if he picks up a few more faiths every day will be a holiday. He is a thoughtful, observant boy who considers matters deeply and wants to understand. In the lifeboat, he considers his options carefully, making an inventory of the food and equipment and lashing together a small raft to protect himself from the hungry tiger. As it becomes clear that they will have to sustain themselves for an indefinite time, Pi uses what he knows about animals to establish his territory and earn the tiger’s trust. In a sense, his life has been simplified to its essence, as everything — home, family, plans, community, food, water, — is taken from him. In another sense, these losses open him up to a depth and spiritual richness that would not be possible in a busy world of connections and obligations.

Pi and Richard Parker weather storms. They share unexpected riches when flying fish literally jump into their laps, and soul-expanding beauty, especially a great luminous leap by a whale the size of a motor home.

When he was a young boy, Pi tried to feed a tiger. His father arrived just in time to prevent him from being the tiger’s lunch and gave him an unforgettable lesson by making him watch as the tiger attacked a live goat. Pi insists that he can see the tiger’s soul in his eyes. His father insists that there is nothing behind his eyes but the law of the jungle. Pi has a great heart and the gift of faith. Both are tested. And it is only when everything he thought he could not live without is taken from him that he realizes how much he has gained, and how it is the troubles he has faced that have kept him alive.

The rapturous visual beauty of the film is itself a spirit-expanding experience. The lyrical poetry of the images and the skillfully immersive effects surround us with a powerful sense of connection to the divine.

Parents should know that the plot concerns a boy lost at sea with a Bengal tiger and it includes sad deaths of family members and animals, some graphic and disturbing images, and extended danger and peril.

Family discussion: Why does a character say the story will make you believe in God? Which story do you prefer? How did Richard Parker keep Pi alive? What do we learn about Pi from his questions about the dance? From his reaction to the island?

If you like this, try: the book by Yann Martel

Have you seen “Life of Pi?” Would you like to read the book? I have a copy of the movie tie-in edition of the book by Yann Martel to give away. Send me an email at moviemom@moviemom.com with “Pi” in the subject line. Don’t forget your address! (US addresses only.) I’ll pick a winner at random on December 8. Good luck!

Have you seen “Life of Pi?” Would you like to read the book? I have a copy of the movie tie-in edition of the book by Yann Martel to give away. Send me an email at moviemom@moviemom.com with “Pi” in the subject line. Don’t forget your address! (US addresses only.) I’ll pick a winner at random on December 8. Good luck!