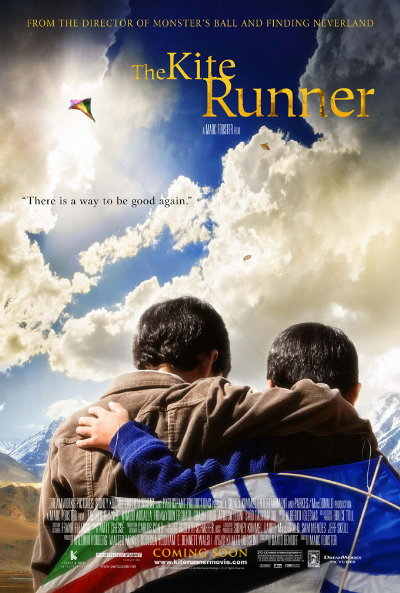

The Kite Runner

Posted on December 14, 2007 at 8:00 am

B+| Lowest Recommended Age: | High School |

| MPAA Rating: | Rated PG-13 for strong thematic material including the sexual assault of a child, violence and brief strong language. |

| Profanity: | None |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | None |

| Violence/ Scariness: | Disturbing material including child abuse, rape of male children and attempted rape of adult woman, woman stoned to death, abuse by occupying Soviet soldiers and by Taliban |

| Diversity Issues: | A theme of the movie |

| Date Released to Theaters: | December 14, 2007 |

This faithful adaptation of the worldwide best-seller puts a struggle for personal redemption and atonement in the context of devastating divides, ethnic, cultural, poltical, and moral, set in Afghanistan before, during, and after the Soviet invasion of 1979. Loyalty, betrayal, even identity itself are themes that echo and circle back on themselves in this moving story of learning what it means to “be good again.”

Amir (Zekeria Ebrahimi as a child, Khalid Abdalla as an adult) is a shy, bookish child who cofounds his stern father, called Baba (the magnetic Homayoun Ershadi). Amir’s closest friend is Hassan (Ahmad Khan Mahmidzada), the son of the family’s servant. Hassan is brave, athletic, and a devoted friend. Although they are from two different worlds, not just master and servant but elite Pashtun and lower-class Hazara. That does not matter to them as they live in a world of their own. Hassan loves to hear Amir’s stories. They both love Steve McQueen movies. And, like the other boys in their community, they love to fly kites.

Kite-flying is a contact sport in Kabul. The kite strings are fitted with razors. The most skillful boys fly their kites close enough to the others to slice them off their strings without getting cut themselves. The winner is the last kite flying and it is an honor to be permitted to retrieve the last fallen kite to present it to the winner. Baba, once a kite champion himself, is finally proud of Amir when he successfully defeats all of the other kites. Hassan runs off happily to bring back the last fallen kite. But it has landed in an isolated site, and he is cornered by bullies, furious because he stood up to them earlier. They offer him a choice — the kite, or the chance to walk away without being attacked. But Hassan had promised Amir the kite and is willing to endure any abuse to give it to him.

He does not know that Amir is hiding nearby, watching helplessly. As one young friend makes a terrible sacrifice and the other a terrible betrayal, their lives are torn apart. Very soon, Hassan and his father leave Baba and Amir, and soon after that Baba and Amir flee the invading Soviet Army, barely escaping to America.

The movie opens with the publication of the adult Amir’s first novel. He is happily married to a fellow expatriate, living in America. But the pull of the past calls him home as Baba’s friend tells Amir that it is time for him to return to Kabul to rescue Hassan’s son, now living under the cruel regime of the Taliban.

Director Marc Forster (Monster’s Ball, Finding Neverland

) places this absorbing story in a setting that is both exotic and universal. China fills in as Kabul but Amir and Hassan are played by Afghani boys speaking in their native Dari. Their surroundings may be very different, but the essentials are familiar — a father worries about his son, and a son wants his father to be proud of him. They do not always communicate well. Boys love to play. Bullies are cruel. And everyone loves Steve McQueen, even in Farsi.

The moment of the assault on Hassan tears the friends apart like the razor slicing through the kite string. Amir, overcome with shame and survivor guilt, can no longer look at Hassan and so he commits a truly unforgiveable second betrayal, as though to persuade himself that the first never happened, or worse, that Hassan deserved it. And then Amir and Baba are themselves sundered from their home. As they escape, Amir learns something from his father of how honorable people think about risk and values, a moment that will stay with him as he and Baba adjust to a new life in an indifferent land, with new lessons in love and loss, and as he returns to his home to find much changed, but much the same.

Forster and cinematographer Roberto Schaefer make us see the dust, the light, the curves of architecture in 1970’s Kabul, the elegance of Baba’s home, the casual bigotry of a world where it would never occur to anyone that Hassan, like Amir, should go to school. The decision to have much of the Kabul dialogue in Dari with subtitles — and the decision to cast mostly native speakers — gives the story authenticity but the natural performances keep us close to the characters. There are some overly-convenient coincidences and connections, but the themes of the story resonate deeply.

Parents should know that the film includes a great deal of disturbing material including child abuse, rape of male children and attempted rape of adult woman, a woman stoned to death, abuse by occupying Soviet soldiers and by Taliban, violence (offscreen and on), and sad deaths. A strength of the movie is its sensitive portrayal of racial and religious prejudice and its consequences.

Families who see this movie should talk about what made Amir so angry with Hassan. Why was Hassan so patient with Amir and so loyal to him? What do the kites symbolize? How did what happened to Hassan as a child influence Amir’s commitment to rescuing his son?

Families who like this movie will also enjoy the book and the films The Namesake

and Secret Ballot

. Charlie Wilson’s War

gives the American side of the story of the Afghan defeat of the Soviets and the consequent rise of the Taliban.