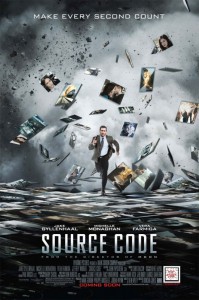

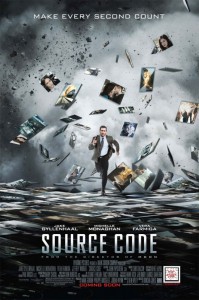

Duncan Jones, with only two films, has already established himself as an exceptionally able director. He wrote and directed his first film, “Moon” with Sam Rockwell, and it was remarkably assured, impressively creating a fully-realized future world that was believably normal — and on a tiny budget. His first big-budget film is another sci-fi story, “Source Code” with Jake Gyllenhaal as a man sent back in time by a military operation to relive the same eight minutes over and over until he can locate a bomber. I met with Jones in the wonderful circular Chimney Stack Room at the Georgetown Ritz and we had a great talk about my home town of Chicago, where the movie is set, about the movie’s secret tribute to the 1980’s television show, Quantum Leap , and about how his father, rock idol David Bowie, got him hooked on science fiction.

, and about how his father, rock idol David Bowie, got him hooked on science fiction.

I’m from Chicago and I loved all the Chicago scenes in the movie!

I’m so glad. You’re the first person I’ve talked to other than the people who worked on it who can say we got it right. It was the first time I’ve ever been in a helicopter and it was stunning to be able to fly through the skyscrapers in Chicago. Incredible, amazing.

I loved seeing The Bean in the movie.

It’s a beautiful park. That whole area is lovely. And a great city.

And you used the Chicago commuter train through much of the movie, with its characteristic double-decker seating.

We took the real train a number of times to get a feel for it and take reference photographs and everything. And then we built our own in Montreal. The funny thing was that the real trains, a lot of the carriages date back to the 50’s and 60’s. They’re beautiful, but they look so period in some ways. We had to update the interior a bit or people would think he was really time-traveling!

I had just finished “Moon” and was doing the press tour for that. In Los Angeles, I had the chance to meet with some of the people I wanted to work with, and one of those was Jake Gyllenhaal, an amazing actor, very handsome, very talented. I was pitching ideas to him, and he said, “I have this script you should really read,” an original spec script by a young guy called Ben Ripley. It was a great read, fast, started off with an incredible ten pages and then keeps up that pace the whole way along.

I made my suggestions – I said, “I think the tone is quite serious. I wonder how you might feel about injecting a little bit of humor into it.” He liked that and we agreed that was what we wanted to do.

For you as a director, it is a real challenge as your main character repeats the same eight minutes over and over again to keep it fresh and interesting and different for the audience.

Yes, one of the most terrifying aspects of this script for a film-maker is how do I keep going back to this same event six or seven times and not bore the audience to tears. I had a graph and I literally worked it out on a visual level how each iteration would be different, whether we used a different angle or went to a different part of the train or move to the upstairs, always keeping variety there. And then narratively, we made sure there was no replication, always something new going on, something learned by Jake, a new relationship, new people. You still have the same eight minute event with continuity but no sense of replication.

We also get a montage taste of other trips back but about six in detail.

Why was the humor important?

I am a big science fiction fan myself. I see it divided up into hard sci-fi and soft sci-fi. Hard sci-fi is where you extrapolate into the future from where we are now and work out incrementally how we get from now to this point in the future. “2001” is a good example of a future you can believe might exist and you can see how we could get there. You understand it could actually happen. Soft sci-fi is a little more fantastical. It can have dragons or magic. And for me, time travel is in a gray area between the two.

I have a hard time believe it is possible but I love it as an idea and I understand the theoretics of it. My approach was, “Let’s use humor to cajole those like me who might not believe that it is possible,” to just say, “Take this leap of faith with me into this world where it is possible, just accept it because the story and the ride is worth it.” Humor does that. It is a very powerful tool in film because if you can get the audience and the protagonist to be laughing about the same thing, to be sharing a joke, in a way, or finding something amusing, the audience bonds with the character automatically.

When I saw the film, I wondered if you had changed the original ending.

We did, but not in the way you’d expect. There was a very sweet, romantic ending that beautifully finished that side of the story, the relationship side. But I am a sci-fi geek and I wanted to deal with this loose thread back at the facility.

It is a challenge to create a character who is interesting enough to play the villain but – without giving too much away here – not so interesting that he throws the movie out of balance, given the direction things end up going in the last third of the film.

I saw this documentary, “The Nuclear Boy Scout,” about this boy in the Midwest, about 15 years ago, trying to qualify for a Boy Scout merit badge in nuclear physics, incredibly smart but no comprehension about right and wrong and built a breeder reactor in his mother’s back yard, just going to antique stores and the library. He was able to create a breeder reactor. The government had to clean it up. Just because you’re smart doesn’t mean you have good judgment; that was where we started. As for casting, if you go with a bigger name, it makes it immediately obvious that if you do that you draw attention to that person. The actor we found, I had seem him at a casting session on video and I said, “There’s something about that performance in particular that captures what I saw in that documentary.”

You pay tribute in the film to some other sci-fi movies.

There were lots of references and parallels, including Quantum Leap , the TV show. My homage to that was the voice of the father: it’s Scott Bakula. He actually says, and we slipped it into the dialogue so it’s very organic, “Oh boy.” So the fans of the show will get that!

, the TV show. My homage to that was the voice of the father: it’s Scott Bakula. He actually says, and we slipped it into the dialogue so it’s very organic, “Oh boy.” So the fans of the show will get that!

Throughout the film there are subtle homages to Hitchcock, here and there. The soundtrack has a Hitchcock vibe to it, and the setting on the train and the clock tower.

Who did the soundtrack?

Paul Hirsch, the amazing editor we had on board – he edited “Empire Strikes Back, “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” “Ray” – he’s a legend. He recommended Chris Bacon, this very young composer he had just worked with. We met with him at 11:00 at night, the day his wife had just given birth and he looked like a walking zombie. We hit him with all this information and told him what we wanted, something mischievous and mysterious, and said, “Can you write us something to see if you’re the right guy?” and four days later he came in with the opening theme as is.

It sounds like you worked very fast on this film.

Jake was finishing “Prince of Persia” and was going to disappear to do press for it. So we had about 35 days, about the same as “Moon.” I think that helps give it a sense of urgency; that energy does translate sometimes.

Have you always been a sci-fi fan? Books and movies?

Books first in fact. My dad is an avid reader and ever since I was a kid, I would read an hour a night. He always wanted me to read so if ever I was finding it difficult to get interested in something, he’d pull out Animal Farm or The Day of the Triffids

or The Day of the Triffids to get me back in. “Blade Runner” is the be-all and end-all for me in science fiction. I strive to make something one day that has the sense of scope. It feels like you could pan the camera away from the actors and you would still be in that world.

to get me back in. “Blade Runner” is the be-all and end-all for me in science fiction. I strive to make something one day that has the sense of scope. It feels like you could pan the camera away from the actors and you would still be in that world.

My next film is science-fiction, too. My first film, “Moon,” was made for very little money. This is more of a Hollywood film. I’d love to take one of my own projects and make it with a “Source Code” kind of budget.

What do you look for in a project?

Empathy. The idea of identity, who someone is, whether the person they think they are is who everyone sees them as. Mostly that the audience can understand and feel for the main protagonist, that connection between the audience and the person whose story you’re seeing. My next one is science fiction and then I’m going to take a sabbatical and try something different.