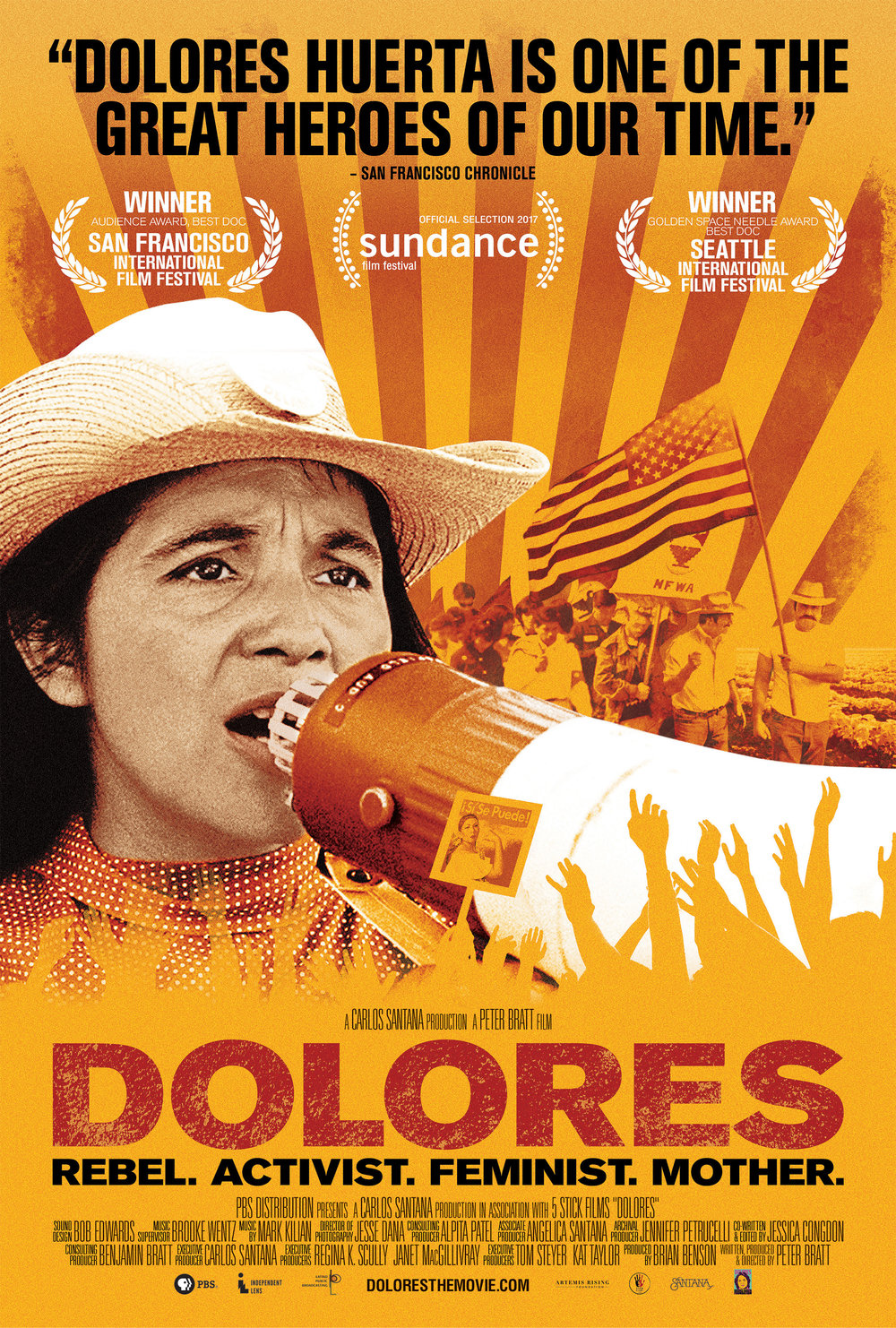

“Dolores” is a new documentary that tells the story of activist icon Dolores C. Huerta, president and founder of the Dolores Huerta Foundation, co-founder of the United Farm Workers of America. If Ginger Rogers is known for matching Fred Astaire’s steps backwards and in high heels, Huerta was as responsible as the better-recognized Cesar Chavez for bringing the attention of the world to the rights of immigrants, women, and farm workers while raising eleven children as a single mother and constantly being marginalized and underrated because of her race and gender. I spoke to Huerta, who was awarded the nation’s highest civilian honor by President Barack Obama, along with the director of the documentary, Peter Bratt.

In the film, we see you begin by sitting down in living rooms or talking to farm workers in the fields to encourage them to insist on fair treatment. What did you say to them?

Dolores Huerta: When you are organizing a group of people, the first thing that we do is we talk about the history of what other people have been able to accomplish; people that look like them, workers like them, ordinary people, working people, and we give them the list. These are people like yourself, this is what they were able to do in their community. And then we talked about the issues that they’re facing in their own community and then we would say to them, “Well, just like these other people did, they were able to accomplish all these great things. You can do the same thing. But the thing is that you got to do it because if you don’t nobody else is going to do it for you; nobody else is going to come into your community and solve your problems. So you have to take on the issues yourself. You’re the ones who have to volunteer to make the work happen.”

So we do a whole series of these little house meetings and you probably get a hundred and fifty people together and out of that group then you have a cadre of them that will come up and they’ll volunteer to do the work that needs to be done and that’s how the leaders are developed. When you go into a community you’ll never know ahead of time who the leaders are going to be. The leaders come up from the volunteers that do the work and it’s amazing because then they do these incredible things in their community that they never thought they had the power to make that happen. Basically, the message is: you have power, the power is in your person and you can make this happen but you can’t do it alone; you’ve got to work with other people to make it happen, you have to make a plan and you have to volunteer. And it works; it’s like magic.

You go out there and you find those people that have this burning passion that they want to change things and you basically are just giving them the tools. This is the way that you do it: you come together with a group of people, you pass petitions, you go to the city council, you go to the board of supervisors and you can make it happen.

Peter Bratt: She actually was telling me a story that she hopped on a Greyhound to northern central California, throughout the bus ride was expecting sixty to seventy people at a house meeting which had only one person, and she said she gave it her all because one person can be the most incredible leader that can change thousands of lives. That was a great lesson.

Why was it important to you to tell this story?

Peter Bratt: Dolores in my view challenges the three pillars of society. She’s challenging patriarchy and yes, that’s part of gender discrimination but it’s also racial. She’s also a Chicana; she’s a woman of color. The third one is as a labor activist she’s challenging the institution of capitalism, and I think those are the three great threats and that made her dangerous. I think those complexities combined to keep her in the margins.

The people who appear in the film are very candid and sometimes very emotional. How do you as a filmmaker develop a sense of trust so that they will share those memories and feelings?

Peter Bratt: I have some history with Dolores. I’ve known her for a little while and I think there was initially a great amount of trust between her and myself and Carlos Santana whose idea this was, and I also knew a few of her daughters from years back. So I think initially there was trust but you still have to prove yourself and earn even more trust. The most important thing as a director is you have to create a safe environment where you make the person feel safe enough to open their heart and reveal the soul; that’s ultimately where you’re trying to get. We interviewed probably about fifty people and the ones that we selected for the film were the ones who we felt truly opened their hearts and spoke their truth.

What has surprised you in terms of how far we’ve come and what has been the most persistently frustrating?

Dolores Huerta: Women are now 50 percent of the law schools and medical schools, so we can look at all the progress that we’ve made, but we can see all the progress that we still need to make and now with the voter suppression going on and with the racism rearing its ugly head we know that we’ve got to really step up our game on the progressive side and get people to vote because a lot of people aren’t voting. They’ve taken civics out of our high schools. People were asleep but I think they’re waking up now. Trump has given everybody a good kick and people are waking up and realizing they’ve got to get involved. That’s the message that we want to send with the film; for people to get involved at the local level, at the community level, at the state level and international level because we can’t afford to let the right wing take over our country. My son Emilio is running for Congress to continue the fight for social justice.

Peter Bratt: Sometimes I just want to put the covers over my head and stay in bed and I feel like no matter what I do it’s ineffectual and I get depressed. So for me having spent these last few years with Dolores, to see her not just doing the work but impassioned about doing the work and getting out there at the grassroots level and she still goes out into the fields in 100 degrees to organize this farm operation, she’s still doing it in the school boards, on water boards, she’s been getting people involved and to see her so engaged and relentless. The fortitude is awe inspiring and yet there is this joy and this passion while continuing to do the work, It encourages me to like quit feeling sorry for myself and get back out there. To me as a filmmaker that’s the biggest reward, to see people lift themselves up and recommit themselves.

A briefer version of this interview originally appeared on the Huffington Post.