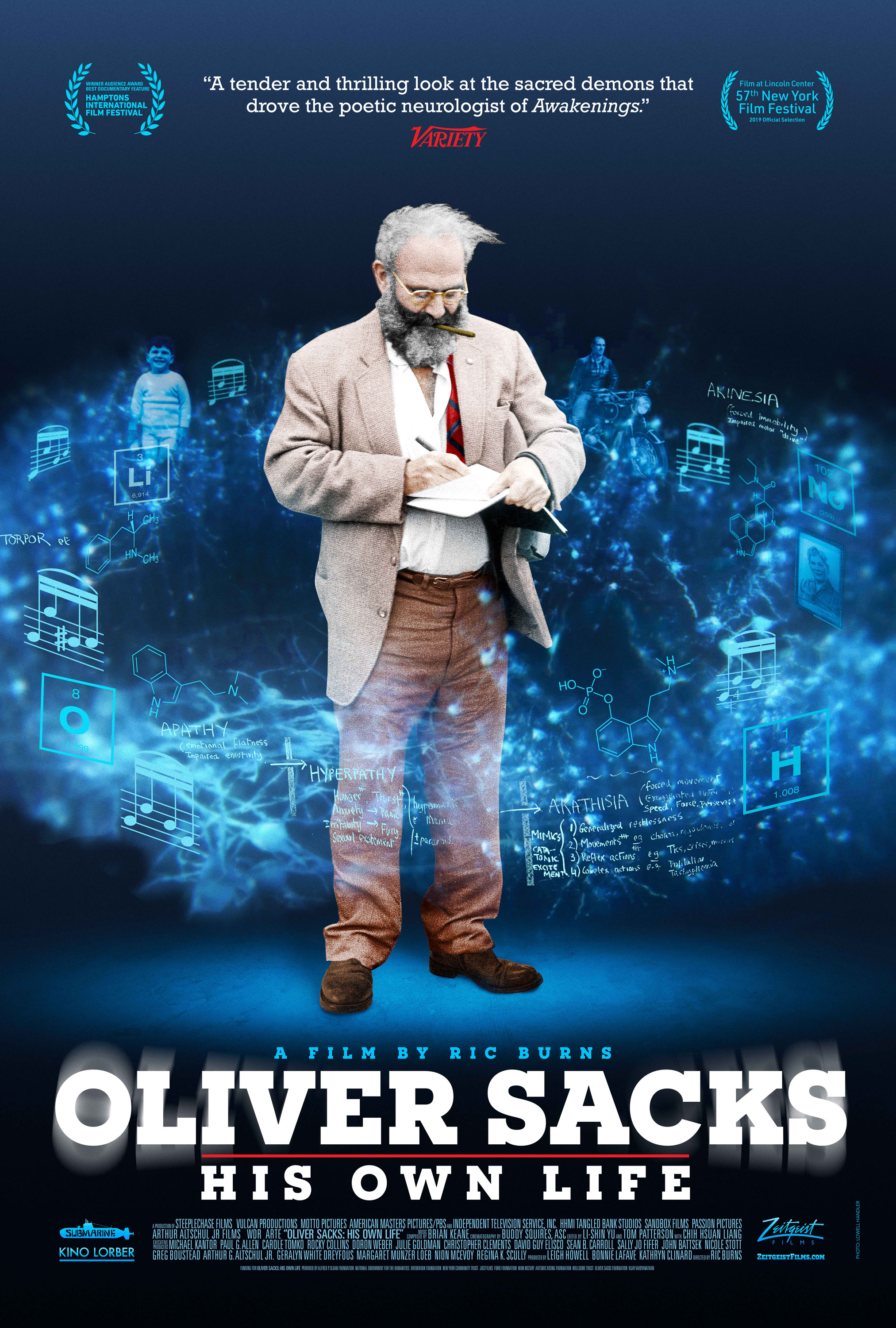

Oliver Sacks: His Own Life

Posted on September 22, 2020 at 5:52 pm

B +| Lowest Recommended Age: | High School |

| MPAA Rating: | Not rated |

| Profanity: | Some mild language |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Drinking and drugs |

| Violence/ Scariness: | References and some archival footage of illness and disability |

| Diversity Issues: | A theme of the movie |

| Date Released to Theaters: | September 23, 2020 |

Oliver Sacks has, by any measure, an unusual brain. He has face-blindedness, for example, the inability to recognize even the faces of people he knows very well. And he has an exceptionally unusual combination of the kind of deep humanity that often accompanies empathy that can make it difficult to maintain observational objectivity. But what makes him unusual is that he also has the objectivity to be an exceptional clinician. The post-encephalitic patients had sad for years without any effort to help them before Sacks, who was coming for research, not clinical practice, came up with the idea of treating them with new medication that was being used to help people with Parkinson’s. He has, one commenter tells us, “the moral audacity to think something is alive in there.”

Very significantly, we learn in this film, Sacks revitalized the concept of the medical case study, which was considered outdated in a world driven by data. The case study is like a little novel. It is about the person, not the symptoms. Early in the film, Sacks tells us that he is equally a writer and a doctor, and we can see how each plays a part in his understanding of his patients. He says the primary diagnostic question is, “How are you?” He saw the symptoms as a reflection of cognition and perception, not just a reflection of brain damage or dysfunction. And framing the patient’s experience as a story is in itself therapeutic, making the case for sympathy and imagination. “His attention would release people.” They would be “storied back into the world.”

Sacks, who sees the patients with such wholeness and compassion, is compartmentalized himself. There is not only the writer/doctor split. His middle name is Wolf, and he sees himself as both Oliver and wolf, a yin/yang brain/body divide. He has been criticized for being an observer rather than a theorist, but as Grandin points out, without observation there is nothing to theorize about. Many people had the chance to observe the post-encephalitic patients, but Sacks observed something in them no one else did, and that observation included possibility of change.

In one of his books, Sacks wrote about a patient who could “hear” words spoken but not the inflections that reveal context and emotion, so very concrete and literal, and one who was the opposite, unable to comprehend language but acutely sensitive to tone and expression, who was thus in some ways better at discerning meaning. Sacks’ own superior observational skills were in part made possible by the deficits that eliminated distracting data.

Sacks relies on the support of others in his own life, outsourcing many tasks and even emotions and relationships. He has been in psychoanalysis for half a century. He took a lot of risks and abused drugs in his 20s. He gets help from his editor and close friend on some of life’s mundane details. After a one-night-stand on his 40th birthday, he did not have sex again for 25 years, and it was not until his 60’s that he had a close, intimate romantic relationship. And. we learn, early on in the film, he has been told he has only months left to live. With the same clinical distance he showed toward his own medical issues in A Leg to Stand On, he observes himself as a patient as he creates for us “a master class in how to die.” But it is also a master class in how to live, as he says, how to live with what can’t be changed and frame it as a story to give it meaning.

Parents should know that this movie includes frank discussion of drug abuse and sex as well as depictions including archival footage of people who have serious medical challenges. There is also a reference to Sacks’ own recovery from a serious accident.

Family discussion: How did Sacks’ experience as a child affect his decisions in his career? How did being a writer and a doctor help him be better at both?

If you like this, try: “Awakenings” and Sacks’ books