Social network sites risk infantilizing the mid-21st century mind, leaving it characterized by short attention spans, sensationalism, inability to empathize and a shaky sense of identity, according to a leading neuroscientist.

The UK paper The Guardian reports that Lady Greenfield, professor of synaptic pharmacology at Lincoln college, Oxford, has found that

children’s experiences on social networking sites “are devoid of cohesive narrative and long-term significance. As a consequence, the mid-21st century mind might almost be infantilized, characterised by short attention spans, sensationalism, inability to empathize and a shaky sense of identity”.

…

Social networking sites can provide a “constant reassurance – that you are listened to, recognized, and important”. Greenfield continued. This was coupled with a distancing from the stress of face-to-face, real-life conversation, which were “far more perilous … occur in real time, with no opportunity to think up clever or witty responses” and “require a sensitivity to voice tone, body language and perhaps even to pheromones, those sneaky molecules that we release and which others smell subconsciously”.

She said she feared “real conversation in real time may eventually give way to these sanitized and easier screen dialogues, in much the same way as killing, skinning and butchering an animal to eat has been replaced by the convenience of packages of meat on the supermarket shelf. Perhaps future generations will recoil with similar horror at the messiness, unpredictability and immediate personal involvement of a three-dimensional, real-time interaction.”

This seems a bit of an over-reaction to me. Young people will make a lot of mistakes on Facebook and other social networks as they do in other aspects of their relationships. This time of life always has been and always will be a stage characterized by intense feelings and difficult lessons. Social networking has its disadvantages — the ability to hide behind partial or full anonymity, the capacity for almost-instant escalation and distribution, the invasions of privacy. But it also has its advantages as a form of training wheels for the difficult relationship navigational connections. Adam Gopnick writes in a touching essay included in Through the Children’s Gate about how his 11-year-old could not answer the question “How was school today?” in person but was happy to communicate with him via instant messaging. They would even IM each other while sitting together watching a game on TV. Gopnick, initially thrilled by this mode of communications, ran into his own failure of understanding, but it all ended sweetly, with love and laughter.

about how his 11-year-old could not answer the question “How was school today?” in person but was happy to communicate with him via instant messaging. They would even IM each other while sitting together watching a game on TV. Gopnick, initially thrilled by this mode of communications, ran into his own failure of understanding, but it all ended sweetly, with love and laughter.

In the New York Times, Peggy Orenstein reports Growing Up With Facebook about the way the past is not prologue but present on Facebook. Orenstein, like Slate’s Brian Braiker, was disconcerted to find herself tagged in pictures from her past that went from being tucked away in shoe boxes to being available to everyone. She wonders about the effect this will have on young people who no longer will have the freedom to cast off old roles and relationships when they go away to college.

There’s some evidence that college students have mixed feelings about being guinea pigs for the faux-friendship age. One student interviewed for a study of why and how college students use Facebook, which was published last year in The Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, admitted that being privy to the personal details of “friends” who she had not seen in years made her uncomfortable. “Someone from earlier in her life had broken up with a boyfriend,” an author of the article, Sandra L. Calvert, a professor and chairwoman of the psychology department at Georgetown University, told me. “She felt she knew all these intimate details about this person, yet they hadn’t actually been in touch for five years.” On the other hand, a study published in 2007 in The Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication suggested that hanging onto old friends via Facebook may alleviate feelings of isolation for students whose transition to campus life had proved rocky.

…

It could be that my generation was the anomalous one, that Facebook marks a return to the time when people remained embedded in their communities for life, with connections that ran deep, peers who reined them in if they strayed too far from the norm, parents who expected them to live at home until marriage (adult children are already reclaiming their childhood rooms in droves). More likely, though, the very thing that attracts us oldsters to Facebook — the lure of auld lang syne — will be its undoing. Kids, who will inevitably want to drive a stake into the heart of former lives, may simply abandon the service (remember Friendster?) and find something new: something still unformed, yet to be invented — much like themselves.

Or, perhaps they will evolve with Facebook and it will evolve with them. Instead of swapping pictures of friends behaving badly at keggers, perhaps they will post baby pictures and cupcake recipes. It is likely that some future Facebook group will be a place for the parents of young children in 2025 to talk about how to cope with whatever impact the latest technological innovation is having on their school-age children.

In the meantime, parents need to remind their children that middle school and high school friendships are tough enough without broadcasting their most humiliating aspects to the world. Parents should, of course, talk to kids about being respectful and responsible in relationships online and in RL (real life) and most of all make sure that they demonstrate the behavior they want to encourage. The more parents do to show kids that the greatest satisfaction comes from in-person communication in a context of trust and kindness, the more likely that social networking will be an adjunct to and not a replacement for the real thing.

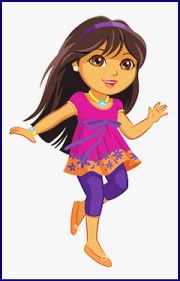

Thanks to everyone for the thoughtful comments on the new “Dora.” I promised to follow up, so here is the latest picture of what the older version of Dora will look like.

Thanks to everyone for the thoughtful comments on the new “Dora.” I promised to follow up, so here is the latest picture of what the older version of Dora will look like.