The Russo Brothers Tell Us What to Know Before Seeing “Captain America: Civil War”

Posted on May 5, 2016 at 3:20 pm

Posted on May 5, 2016 at 3:20 pm

Posted on May 2, 2016 at 3:40 pm

John Goldschmidt is the director and co-producer of the film “Dough,” a sweet comedy about an Orthodox Jewish baker (Jonathan Pryce) whose new assistant is a Muslim teenager from Darfur who has a side business dealing weed. The marijuana gets mixed up in the bread, and suddenly the bakery has a lot of new customers just as a predatory developer is trying to take it over and the baker’s son is trying to get him to retire.

In an interview, he told me that he made this film because he was looking for a project that had “something to say about the state of the world that’s particularly relevant but it will also entertain, in other words a film that will treat serious issues with a comedic like touch.” In a film like this one, he said, casting the lead “sets the standard for everything” and attracts the other performers. His casting director, Celestia Fox, called to tell him she had seen Pryce at a party and he had a beard, so he already looked the part. “Jonathan is one of the most celebrated theater actors in London. Once he’s involved, other people seem to say, ‘This is must be a good project.’ So Pauline Collins, who acted with Jonathan Pryce years ago at the National Theater loved the script, knew about me and got involved.

It was more of a challenge to find the young man to play the African immigrant. “I auditioned a lot of people and choose six of them along with Jonathan Pryce to see the chemistry between them.” Jerome Holder won the role. “I chose Darfur as the country for this Muslim boy to come from because I had seen George Clooney’s film about the persecution of the African Muslims in their villages by Arab horsemen. I thought the people looked so beautiful. I wanted to avoid the complexities of the Middle East. I wanted it to be unencumbered by that whole situation. We needed to get all that detail about Darfur and we needed to get Jerome to have an African accent. He’s from a Christian family, a church based family. He had to acquire an African accent for his dialogue. He did very well I thought because I didn’t want it to be too strong for people to be alienated by it and yet he couldn’t really talk like a London guy. I didn’t want him to have a dialogue coach because if you get too self-conscious about these things it can knock around with your head. I just wanted him to retain his naturalness because he’d never been in a movie before.”

Goldschmidt, whose favorite Jewish bakery treat is challah, said Pryce spent a week in a kosher bakery to play a man who has been baking for decades. They shot in Budapest, where they completely replicated the Jewish bakery in North London. “My producers say that a lot of the best films about America are being made by European directors who see America through fresh eyes,” he told me. His own background contributes to his tendency to appreciate cultural differences. “My family are classified as victims of Nazi persecution. I was born in London, I grew up in Vienna. Came to England to go to art school when I was 17. And so in a sense although everyone thinks of me as totally British, I do have a slightly different angle on things. I just liked this particular idea because it’s like the odd couple. It’s about two characters who are as different as possible could be. One is old the other is young. One is black, the other is white. One is Jewish the other is a Muslim. I wanted to make an entertaining, uplifting movie in the end. This is the story of a very unlikely friendship and I wanted to make a film in these dark times where people would leave the cinema with a smile on their face and yet at the same time I wanted to address the issues that I thought one has to deal with in this period that we are living in.”

Posted on April 25, 2016 at 3:25 pm

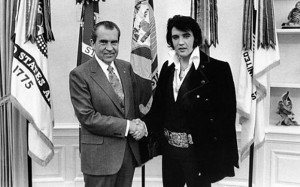

The image of Presley and Nixon standing awkwardly together in the Oval Office is the most requested photograph in the history of the US National Archives. “That dissonance is probably why people are interested in the photograph,” Johnson said. “They’re both very well known to us and they mean something to us. I think Elvis means something more countercultural and Nixon mean something establishment. That’s why it’s weird to see them in the picture together. In a way I think that’s the spin of the movie too.” She said that despite her great respect for Shannon, he would not have come to her mind to play Presley. “I don’t know who I would have thought of but it would not have been him because he doesn’t immediately have any likeness to Elvis or have personality traits that make me think of Elvis or have a repertoire of characters in the past the remind me of Elvis. When I read it, I got it. It has so much intimate depth for the Elvis character and that’s what Mike can do. He has a sort of very sophisticated relationship to drama, comedy. You know Ionesco is his favourite playwright and I knew that honestly once I read it I couldn’t think of anyone who could do a better job of navigating among those properties which were written in the story. We were both were interested in the ways that the script is a bit counter to the most kind of dominant understandings of the characters. People think of Elvis as a glittering brilliant beautiful surface but no one ever thinks about what Elvis might wonder about or what was going on in Elvis’ inner life. With Nixon the opposite is almost true. The most common thing ever said about him is that he is complicated. When people talk about him they talk about his psychological issues and it’s never about his beautiful surfaces or anything. This story suggested two things that we don’t think of. One is that Elvis had an inner life and two is that Nixon, this complicated man who is constantly doing morally compromising things like blowing up Cambodia or actually infiltrating the countercultural movements that Elvis is talking about going undercover in. He had not yet done Wategate at this point but he was doing all these other things so if I were him, I’d be sweating. Yet in this story we can also have a sliver where the main thing he’s doing is not understanding whether he should meet with a rock star. I actually found that charming. Partly because it’s so different from where that entertainment and political culture is at now.”

Instead of Elvis Presley songs, the soundtrack features other music from the era, including Elvis playing and singing along to “Suzy Q.” “You know, Elvis did do stuff like that. In this period he was covering popular music including the Beatles, at least three songs. I didn’t know that; it’s something I found by looking. He did sing some CCR songs and Neil Diamond in this period and I guess he was really kind of a promiscuous lover of all kinds of music including opera. In most of the source music that I put in the movie I really wanted to focus on the regional, southern, like 1970’s soul into funk period. I think that it reflects something about the place and time.”

She found Shilling’s insights especially helpful. “The thing that I learnt the most from on this project was actually Jerry Schilling’s book, Me and Guy Named Elvis, which is a really beautiful and intimate account of their friendship. It’s a very self-reflective. He is either a genius or he’s been to a lot of therapy. He has a real capacity to reflect on himself which is very unusual. That book is like a real anatomy of what it’s like to be the friend of a superstar and I really recommend it. It was like a very guiding document for me and also I got to work with him. I got to be friends with him, and I think his story is not the typical one of someone who hangs out with a superstar. Jerry stayed friends with Elvis for his entire life precisely because he took some measure of distance at some crucial moments. The other guys didn’t necessarily do that and that didn’t end well. I feel like there is a profound lesson about friendship in there about what is beneficial about closeness and what is beneficial about distance.”

Posted on April 14, 2016 at 3:42 pm

James Napier Robertson is an actor turned writer and director from New Zealand who played hundreds of chess games with the real-life champion who inspired his film, “The Dark Horse,” and with the actor who had to learn chess — and put on 60 pounds — to play the role, Cliff Curtis. In an interview, he talked about the late Genesis Potini, the Maori speed chess champion who struggled with bipolar disorder and worked with underprivileged children, teaching them chess and a lot more.

Robertson said he considers himself “fortunate” to be a chess player. “I think it depends who the teacher is who is bringing chess to you that decides how revolutionary it might be. And I think with Genesis that was one of the things that I was immediately drawn to — his ability to take a game that normally you would think could be quite esoteric and sort of boring almost to people everyone else had kind of written off and thought that they are not going to be academic let alone interested in something like chess. He would make them love it and get excited about it and kind of open up the personality of the game and of the characters within the game. So I think that that’s what’s exciting about it for me, particularly in the way that Gen could weave his magic within it as well.”

He first saw Genesis Potini in a documentary, “and I was immediately struck by this guy, this incredible character and how intelligent and articulate and sort of philosophical he was but also how there were contradictions to his complexities and the eccentricities. So I immediately went and met with Gen and as soon as I walked into his house he was standing there in pink crocs like the character is wearing in the movie and tights and he had some nunchucks and he did like a nunchuck dance thing for myself and Tom, the producer. Of course we just sort of stood there stunned like, what do you say? And then I sat down across the chess board with him and we played a game of chess and I managed to lose but lose gracefully and hang in there long enough that I think it kind of opened up a modicum of respect for me from him that I appreciated the game and that I wasn’t kind of a tourist in that regard. I actually cared about what he cared about. We played hundreds of games of chess, hundreds and hundreds and we just talked. We talked all about his life and his experiences and things that had happened to him and in the meanwhile I started putting together a screenplay.”

Potini was taught by Ewan Green, a New Zealand master, who then taught Curtis to play for the film. “So there was a beautiful kind of symmetry. Me and Cliff still play fiercely to this day. Just two days ago we had another few games and he wanted me to very proudly state that he won the most recent one. It really depends on the day that you ask that, who is currently on top.”

Although Curtis is probably the internationally best-known actor from New Zealand and, like Potini, is Maori, Robertson did not initially consider him for the role. “I hadn’t thought of Cliff really because as talented as he is he is a slim, good-looking guy and Gen, the real Gen that I knew was a big guy with bad teeth and funny haircuts and so it just seems like such an incredible leap. Cliff actually got given the script by an actor that we were looking at for a different role in the film. And so Cliff got in touch with us and we started talking on the phone a lot for days and days and days just discussing the possibilities. And then really in the end for me it came down to two things that I felt he would need to do: one was put the weight on and the second one was to method act the role, to stay in character for the entirety of the shoot. And he thought those were both completely insane ideas and there’s no way he was going to do them and fair enough, but in the end I think I just kind of wore him down and he eventually saw the light in that sense and so he put on close to 60 pounds in a little over 6 to 8 weeks, a lot of milkshakes and a lot of beer. He read that the beer was a very good way to quickly fatten the body up and he stayed in character for the whole of the shoot. Once we were shooting, there was no Cliff Curtis there was only Genesis, he would stay and wear the clothes all the time. There were some mornings I showed up on set at 5:30 in the morning and my first ID told me Cliff’s already here, he’s been here half an hour before everyone because he’s been wandering the streets all night and he just walked to where we are shooting. So the commitment from that man is remarkable. Once he got his head around it he was in.

The film is wisely very frank about the realities of both mental illness and the poverty and violence of Potini’s community. “A lot of the exploration of that in the film came initially from my conversations with Gen and really discussing in-depth, as much depth as he was comfortable discussing, his own experiences, also talking closely to his family and friends about things that Gen had gone through in the past. I did an immense amount of research and very kind of respectful study into particularly what the more extreme aspects of bipolar can be. We all to a lesser or greater degree can relate to the ups and downs of bipolar disorder. Often the temptation for a film is to take something like that and then manipulate it to kind of help a narrative to tell the story in the way they want. Right from the beginning that was something I was never prepared to do. I always made it very clear and drew a line in the sand with that that the film will be an honest, respectful but unflinching look at what that really feels like and what that’s really like for someone to go through. It was important that the film not try and disingenuously portray that there’s some sort of happy ending cure to that, that in a way if we win a tournament or if we achieve our goals in life somehow that fixes all or problems because it doesn’t and that’s not how life works. And that was something that I had to really fight for because obviously in order to make a movie you need a lot of money and with that comes very strong opinions on what will work and what won’t work and what people might want to see versus what people might be put off. I know there was a lot of fear that the film’s honesty in that way might be too much for people to put up with. So I had to really kind of go on a bat for that and say that I firmly believe that people will be far more connected and moved by something that feels like a respectful and truthful depiction rather than something that’s manipulative.”

The children in the movie were not professional actors. “These kids come from backgrounds pretty similar to the characters they were portraying in the film. One of the things was finding it hard to limit how many of kids we had because there were so many incredible kids that we found out there. I feel extremely lucky that we got the kids that we did in the film but some of them like the boy that plays Murray, there was no Murray in the script but my casting director, Yvette, she was like “You’ve got to see this kid he’s just like the most amazing kid you’ve ever seen”. So I watched a clip of him and I was immediately like ‘He’s got to be in the movie.'”

Because the kids were not trained actors, Robertson drew on his own background as an actor to make them comfortable. “It’s pretty intimidating on the set. There’s all these cameras and lights and they’ve never been near anything like this before in their lives. We played a game. I told them, we were going to play a game and they would all pretend to be the characters the whole time. It was funny because about three weeks into the shoot when they had known each other two months I walked past and heard one of the girls lean over one of the boys and say, ‘What’s your real name?’ So they really took this game to heart.”

As for the Maori community, “To be honest, they have just been the most incredible supporters of it. If they weren’t it wouldn’t have been possible because again it was so crucial that it was an authentic portrayal and if it wasn’t people would know that, the real people would know that and they would hate it for that. So again I was always conscious of the fact that this has to be a film that not only can feel honest to people that watch who don’t know anything about this kind of community or the situation but has to feel utterly honest for people. And one of the things with gangs for example is I’ve seen quite a few films and really great films, really, really stunning films but the way the gangs in New Zealand or elsewhere can be portrayed in an almost sort of romantic sense or in a kind of action sense where they are all muscular, oiled up and doing kung fu kicks and fighting and they look badass and it’s all really cool. But that’s not what gangs are really like. There’s a lot of sitting around, there’s a lot of nothing to do, there’s a lot of bad health because of choices made. It’s more of a sad environment and that is what I wanted it to be in the film. I didn’t want it to feel like another version of the action hero gang members; I wanted it to be realistic and that ultimately brought a lot of support. Most of the guys in the gang roles in the film are gang members or ex-gang members and sometimes from different gangs. I was scared because you can’t have these guys from different gangs on the set at the same time, because they normally want to kill each other but the truth of the film was something they really responded to and wanted the story to be told so that so they wanted to be part of it, so it kind of brought them together. And the actor who plays Ariki, the brother in the film, had never acted before in his life, this is the first role he had ever done, he was actually in one of New Zealand’s worst gangs for 15 years and he left because he saw his own son wanted to follow in his footsteps. So for a lot of these guys that are in the film they saw the movie as an opportunity to try and show the young men coming up, this isn’t what you think it is. Like there is a truth to the gang lifestyle that’s hard for them to try and explain but maybe the movie can show. I didn’t want actors that sort of come in and pretend and portray and then leave to a completely different life. I wanted the real people.”

Posted on March 21, 2016 at 3:03 pm

“Everything is Copy,” the documentary about Nora Ephron by her son, premieres tonight at 9:00 on HBO. Ephron was the daughter of Hollywood screenwriters Phoebe and Henry Ephron (“Desk Set”), who named her after Ibsen’s famous heroine of “A Doll’s House” and based their hit Broadway comedy “Take Her, She’s Mine” on the challenges of raising Nora and her sisters. Nora Ephron began as a journalist, and her collected essays about women and media are witty, self-deprecating, and fiercely funny. She often quoted what her brilliant but difficult mother told her as she was dying:”Take notes.” Her parents taught her that everything was material for her writing, and her first novel, Heartburn is the bittersweet, but fiercely funny of her marriage and humiliating break-up with Watergate reporter Carl Bernstein, the second of three writers she married. She wrote the screenplay for the film, directed by Mike Nichols and starring Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson.

She also co-wrote the screenplay for “Silkwood,” also directed by Nichols and starring Streep, and then went on to write iconic films like When Harry Met Sally…, and she wrote and directed Sleepless in Seattle

, You’ve Got Mail

, and Julie & Julia

.

I’m a big fan of her film with Rick Moranis and Steve Martin, My Blue Heaven, a comedy about a long-time crook in the witness protection program, and I think it is very funny that it came out around the same time as “Goodfellas,” a brilliant drama about a crook in the witness protection program, based on a book by Ephron’s third husband, Nicholas Pileggi. Everything is copy, indeed.