Smart People

Posted on April 10, 2008 at 5:00 pm

B-| Lowest Recommended Age: | High School |

| MPAA Rating: | Rated R for language, brief teen drug and alcohol use, and for some sexuality. |

| Profanity: | Very strong language |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Drinking and drug use by adults and teen |

| Violence/ Scariness: | Peril, accident with injury, reference to sad off-screen death |

| Diversity Issues: | None |

| Date Released to Theaters: | April 11, 2008 |

A burned-out literature professor named Lawrence Wetherhold (Dennis Quaid) has written an “unpublishable” book called The Price of Postmodernism: Epistemology, Hermeneutics and the Literary Canon. Of course it is unpublishable. Everyone knows that the part of the title that comes before the colon in literary works is supposed to be self-consciously cutesy. A book like that should be called something like A Bad Slammin’ Groove: Epistemology, etc. I suppose it is a symptom of Lawrence’s ennui and disconnection that he has lost the essential ability for preserving that academic necessity: a snarky combination of smug superiority over popular culture and even smugger superiority over the ability to speak in its patois.

Lawrence, his college-student son James (Ashton Holmes from “A History of Violence”) and his college-applying high school senior daughter Vanessa (“Juno’s” Ellen Page) are each floating around in separate bell jars, suspended in space, all the air sucked out by anger and loss, all three unable to communicate and unaware of how much pain they are in. Lawrence’s brother Chuck (“my adopted brother,” he reminds everyone — played by Thomas Hayden Church) moves in. Yes, he will prove to be the life force confronting the dessicated souls so out of touch with their true feelings. But Church and the screenwriter, novelist Mark Poirier, give him more perspective and more spine than these characters usually display. “These children haven’t been properly parented in many years,” he tells one visitor. “They’re practically feral. That’s why I was brought in.” And he believes it.

Poirier appreciated literature and he knows how to create characters who talk (and don’t talk) about what is going on like educated people. He has not quite worked out the difference between a novel and a movie, however; he still tells too much and shows too little. An exceptional cast takes the material as far as it can go, but it still feels synthetic and its sense of tone is uncertain, biting here (faculty committee, unpublishable tome), sentimental there (how many times do we have to see a grieving spouse who can’t clean out the closet?). Quaid is especially strong and Parker lets us see her sweetness and longing, but Page’s and Church’s characters are underwritten and it feels like it all gets tied up too hastily. The characters might be too smart for their own good, but the movie could use a few more IQ points.

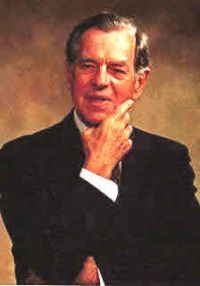

Charlton Heston, who died this morning at age 84, had the screen presence for larger than life, heroic roles, and often appeared in films with religious themes. He will be best remembered for his Oscar-winning performance as

Charlton Heston, who died this morning at age 84, had the screen presence for larger than life, heroic roles, and often appeared in films with religious themes. He will be best remembered for his Oscar-winning performance as