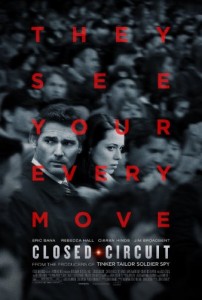

Closed Circuit

Posted on August 27, 2013 at 8:00 am

Terrorism has killed thousands of people, destroyed buildings and property, and caused seismic rifts in our notions of who constitutes “us” and “them.” What is even more terrifying is the damage it has inflicted on our most fundamental notions of privacy and justice. “Closed Circuit” is an up-to-the-minute thriller in which the chases and explosions are less scary than what it reveals about how ineffective our legal system is for responding to terrorism. The damage to democracy may be more devastating than the damage to life and property.

Terrorism has killed thousands of people, destroyed buildings and property, and caused seismic rifts in our notions of who constitutes “us” and “them.” What is even more terrifying is the damage it has inflicted on our most fundamental notions of privacy and justice. “Closed Circuit” is an up-to-the-minute thriller in which the chases and explosions are less scary than what it reveals about how ineffective our legal system is for responding to terrorism. The damage to democracy may be more devastating than the damage to life and property.

The story begins with a shocking terrorist attack at a London market. Two suspects died in the bombing and one died “resisting arrest.” Farroukh Erdogan (Denis Moschitto), described as “the last man standing,” is quickly captured and accused. The traditional judicial system cannot provide him with the rights that are accorded all defendants under UK law, including the right to examine and respond to all evidence against him and to be given any evidence the government has that might cast doubt on his guilt. So he is given two different trial attorneys (called barristers in Great Britain), one for an open hearing, one for a separate closed hearing. The judge soberly advises them that “you must not meet or communicate or share information in any way.”

Martin (Eric Bana) will represent Erdogan in the open hearing to the best of his ability without any access to information deemed sensitive by the government. Claudia (Rebecca Hall) is appointed to have access to those files the government has selected as confidential. In a complicated set of procedures, if she discovers something in those files that is relevant to the case, she can show it to the judge but not to Martin or the defendant. This procedure is intended to provide some some fairness in an inherently unfair process we continue to refer to as the justice system. “There is no right way out of this,” a character will say.

Claudia initially tries to withdraw. She does not explain much but we learn that she and Martin have a history. Even though the process prohibits them from having any contact, that past relationship makes things more complicated.

Separately, Martin and Claudia begin to believe that they are being manipulated, even threatened. But by which side? Is it possible to sustain a democracy, or any kind of accountability, when an official explains, “You want the freedom to attack me, but without me you wouldn’t have much freedom at all?” It is eerily reminiscent of Jack Nicholson’s famous speech in “A Few Good Men” and Jose Ferrar’s in “The Caine Mutiny.” Both accuse us of feeling superior to the decisions we delegate to those who guard our freedom, and our willingness to overlook the infringements of freedom that result.

As an audience, we can distance ourselves from the chases and explosions. Our most terrifying realization is the same one Pogo made famous: “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

Parents should know that this film has very strong language, references to adultery a terrorist attack, chases and fights, suicide, some disturbing images of murder victims, drinking, and smoking.

Family discussion: Read up on the US FISA court and the controversy about NSA access to personal information. How do we balance the need for national security with the fundamental guarantees of individual justice like the presumption of innocence, the right to examine evidence, and the protection against self-incrimination?

If you like this, try: “Four Lions” and “The Ghostwriter”