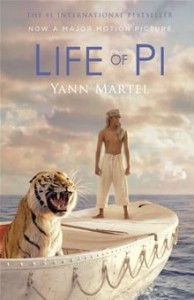

Director Ang Lee and star Suraj Sharma met with a group of journalists to talk about “Life of Pi.”

Lee said the biggest challenge was to “make a big mainstream movie out of a philosophical book that’s beloved.” And it was a challenge to create an illusion that mixed the action and themes so seamlessly that it wouldn’t take people out of the movie. “It’s adventure story, and it is a movie about faith and hope, so we keep a balance, but that’s very, very challenging for the film-maker. Of course, there’s a kid, there’s water, there’s a tiger,” not to mention his first time with 3D and all the CGI.

He was asked whether his vision for this film could have been made a few years ago. “No, I don’t think so. My vision? No. some other vision, probably. You can have a lot more restraint. I think, actually, the use of 3D actually helped to set you out by the water, and also the realism of the animal, and the scope of God’s vision and it provides a lot of new visions, so to speak, tools to visions. I think visual effects-wise, it would be very challenging. It’s not impossible, but it’s hard to believe. I’m still a novice in 3D. Very carefully, I learned very diligently, but after all, we’re just discovering another new cinematic language to enhance not only effects but dramatically where you put things and how you take in the images, soak it in, and take that as the new grand illusion…I think five years ago those elements wouldn’t be there for me. We could still make the movie, but it’s different.”

The water is almost a character in the film. Lee spoke about it. “On the surface, I think, because this is a movie about faith, a young boy, soaking all his innocence with organized religions and society, that he throws into the ocean. So in some ways, water is like the desert; it’s a test of his faith, of his strength and everything, he goes through the journey. And as a film-maker, I like to see the water that carries life, it’s a representation of nature and emotions, and anything that has with water, even rain or mist or cloud formations, that represents some kind of mood that Pi’s going through, so I’d have liked to us the mood, the transparency or semi-transparency for the blocking and the reflection, this is a nightmare for 3D, (by the way, we overcome that obstacle) we use all of that as a way of explaining life, where he looks at the sky, the air, that’s heaven, God and death (to me.) Sometimes they blur, you don’t see the horizon, they blur together. Sometimes they separate, sometimes they reflect each other. I think it’s just a wonderful tool to externalize, to visualize internal key things. I like to use them to express my internal feeling and Pi’s.

He likes to feel that he is scared by his projects, “doing something that will put me on the edge, it’s like Pi facing the tiger, keeping me alert, putting me in the God-zone I need, I need total attention, focusing, and therefore I get the thrill that I’m living life fully, and that’s how I choose to express myself and be seen by people.” He sometimes asks himself, “Why am I doing this? Why, why why?” but he loves the challenge. “I get to learn all these new things about film-making; I’m an avid film-student, I would like to see my career as an extension of film-school. Now I get to learn 3D, how good is that? Somebody’s paying for it….I got these naïve, double-negative thoughts, like ‘if I add one more obstacle, maybe it’s possible,’ and more dimension, maybe I can take that leap of faith. At least, I think, by giving new cinematic language, people might open up, just bring back, just naturally, that innocence of watching a movie, and theatrical experience; maybe that will happen…There’s no way I could do what I did there with 2D. The wave has to be so much bigger, 10 times bigger, to get a feeling. Still, you don’t get that you’re floating there with Pi. I think animal, the animation is more believable, because it has real dimension and depth, and the excitement of finding new ways of expression and putting things in different places, giving the depth and manipulating the depth and your point-of-view, actually that adds a lot to, help you expend a lot of your imagination and exploration, so, all of that is pretty good for the unusual project. You know, I’m a film-maker, I live for that kind of thing.”

Sharma told us about what it was like to make his first film. “I think that if you work with someone as great as , it’s not intimidation, it’s comfort, you know? You feel that if someone can trust you like the way he is, then you just give it everything you have and you trust him back, and in that, everything will be okay. That’s how I saw it, and you know, before we started shooting, there was three months in which I learned a lot of things, there were a lot of things that took place, I met a lot of the crew—and you know, when you get so familiarized with people who are so nice, who become like your family, then you lose that pressure. That pressure is lost, you just become part of the whole process, it becomes something that you do for yourself and you do for everybody who is putting your faith in you for you to do it. I didn’t know how hard it is to make a movie, ever. I thought it was all, honestly, I thought it was all glitz and glamor and stuff, I didn’t have much of an opinion, but just being on set, in itself, taught me so much. You learn about how there are so many things that go into making movies, so many people with all of these different things from all these different places coming together, all who are different at what they do, at what they specialize in, they’re all kind of working together like a machine, just for even, just for maybe three seconds of film. It’s the most inspirational feeling I get, just being on set, that I don’t know—that intensity with which people work, the passion, the fire, it really gets to me. I start feeling like, maybe starting to work, I want to do this so badly. It makes me feel driven. There were moments when I thought,’How am I going to survive this?’ there were moments where I was so dire and so exhausted but everything just seemed to come together. I really like the fact that they put so much faith in me, to make me go on, and that’s what kept me going.

Lee listened and smiled. He said that Sharma was a spiritual leader for the entire crew “because he didn’t know. If he’d known, we would act differently, and he wouldn’t be a leader. We’ve been in the business for a long time. A lot of us can be jaded, can be cynical, we’re still doing what we do best, with passion and everything, but we can really get cynical, get tired, and then when we see something like that, a person who doesn’t know that he’s leading the thing, he’s carrying everything on his shoulder, he still thinks that everybody tells him what to do…there’s a beauty to that, there’s certainly innocence that remind us why we want to make movie in the first place. He doesn’t know, he doesn’t have any comparison. He probably didn’t know what bad acting is, it’s just the way you do it. He didn’t realize that’s the best thing you can do for acting. So that’s treasurable. So we don’t tell him until the last day.