Trailer: Jenny’s Wedding with Katherine Heigl and Alexis Bledel

Posted on July 5, 2015 at 10:00 am

Posted on July 5, 2015 at 10:00 am

Posted on June 11, 2015 at 3:39 pm

In 1975, a Boulder, Colorado county clerk issued six marriage licenses to gay couples, including Filipino-American Richard Adams and his Australian husband, Tony Sullivan. Richard immediately filed for a green card for Tony based on their marriage. But unlike most heterosexual married couples who easily file petitions and obtain green cards, Richard received a denial letter from the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) stating, “You have failed to establish that a bona fide marital relationship can exist between two faggots.” Outraged at the tone, tenor and politics of this letter and to prevent Tony’s impending deportation, the couple sued the U.S. government. This became the first federal lawsuit seeking equal treatment for a same-sex marriage in U.S. history.

The documentary about this couple and their four-decade struggle for the dignity and legal protections available to opposite-sex committed couples, is Limited Partnership, which will be featured on the PBS “Independent Lens” series on June 15, 2015. I spoke to director Thomas Miller about making the film.

We think of marriage equality as a very contemporary issue. How did you discover this extraordinary case from the 1970’s?

I moved to Los Angeles in the early 90’s and came out as a gay man at the same time. And as I started meeting more of my friends; gay and lesbian, especially in Los Angeles, a lot of them were in relationships with foreign partners. And as I watched these relationships get more serious I discovered that the foreign partner could not stay in the United States based on the relationship and the United States citizen couldn’t go to the foreign partner’s home country. And so I started to do some research and I discovered there were almost 40,000 bi-national same sex couples that were in the same predicament. And so in early 2000 I thought that it would be a good idea to start doing a documentary about this. I didn’t know it would take me almost 15 years to finish.

Tell me a little bit about what happened during that 15 year period and in terms of the film and in terms of what happened in the legal and cultural approaches to marriage equality.

In doing the research for the film I came upon Richard Adams and Tony Solomon’s story. I was very surprised to learn that in 1975 there was a County Clerk in Boulder, Colorado who issued six same-sex marriage license and Richard and Tony received one of those licenses. And what was so important to Richard and Tony was that Richard was Filipino-American, Tony was from Australia. And so they used their marriage license to file for a green card for Tony to stay in the country as a spouse of an American citizen and received a letter back from the INS denying the green cards stating that they didn’t believe that a marital relationship could exist between “two faggots.” which was really shocking.

After getting that letter, they were the first same-sex couple in US history to file for equal same-sex marriage rights including immigration rights in the federal government and that was again in 1975. And so the whole story involved watching these two men fight for the right just to stay together against the United States government for over 40 years. And in covering the story you kind of learn the whole history about when they gay and lesbian movement started. And you sort of get the history of how the country has changed in that 40 year time span.

Why has public opinion shifted so quickly on this issue?

Honestly I think it’s because in the 70s, a lot of people didn’t know of people that were gay or they knew people but they weren’t out so they did not know who they were. And over the course of that time period, people have come out I think thanks a lot to people being more accepting. You started seeing TV shows with gay characters in it that weren’t the stereotypical drag queens but just regular everyday people. They weren’t these outsiders. They were just like everybody else. And so as time went on especially the people who started watching those shows are in their 20s and 30s and 40s and so now they are voting age. Now they are the people just going out there making decisions for people of the United States government. And almost everyone knows someone even in their family or close friends who is gay or lesbian or transgendered. So it is not scary to anybody anymore. I think that is why it is so accepted now.

When you were doing research for this film, what were some of the resources that you used? Were you looking at archival footage? Were you looking in libraries?

Yes, I was really lucky. In Los Angeles we have the One Institute, I also did search the archives, I did consult with like immigration lawyers and a few other people. And I started looking at some magazines and articles from around the country again in the archives and that’s what led me to Richard and Tony’s story. And one of their friends connected me to them and I found out that they also lived in Los Angeles and so that was very fortuitous.

And what pressure did this kind of long-term litigation put on the relationship?

think that it put on a tremendous strain on the relationship. Monetarily, Richard had to sort of support Tony, because Tony really couldn’t work legally in this country. Socially they had to sort of remain… I don’t want to say underground because they weren’t really underground but… How can I put it? They faced so many different obstacles from the United States government and sometimes their own community. They had been fired from jobs because they were out and gay and in the media. They lost parts of their family; Tony was disowned because of that. So a lot of pressures. And it just showed the strength of their love that no matter if it was the government, the family, their friends, the community, their jobs that they were fighting that they had enough love to stay together for 40 years.

Actually Tony says that in the 1970’s when a lot of gay and lesbians were just sort of fighting to come out that they did not get a lot of support from the gay community. The people weren’t thinking about marriage rights or immigration rights, they were just sort of trying to express themselves. Their biggest supporters came from the Republican gay group, not the Democrats. A lot of the Democrats, a lot of the gay organizations were maybe afraid of what they verdict might be if they took their case to court so they were against them trying to fight for that. So again the libertarians and the gay Republicans were their biggest supporters.

What did you learn about the legal system either good or bad as a result of working on this movie?

I have learned that being in the United States we’re lucky that we have the chance sometimes to change laws and fight for one’s rights. I am not just talking my gay and lesbian rights, I’m talking about civil rights, women’s rights, African-American rights, eventually we get it right but it just takes a long time. It takes pioneers, everyday people, to start the fight. Richard and Tony were just everyday people that believed in themselves and believed that they were equal and fought for those rights. And I guess the reason we made the film was to show everybody that we can make a difference in the lives of individuals living in United States. It may take a long time but we can make a difference.

And as a filmmaker, what was the challenge for you in telling the story that stretched out over so many years in an accessible way?

I didn’t want it to be a history lesson. I felt like I wanted to show a love story and in showing a 40-year love story, people could learn the struggles of these characters endured over 40 years. And so that was the challenge, how to do that without getting people mixed up; where were we in time? So we had to learn how we use graphics, how to use a timeline to do that, how do you incorporate a lot of archival footage and keep it interesting and make it emotional. And luckily we had some great characters for really unexpected twists and turns in the story and sort of bittersweet ending. One of the things that has been nice for me is that when I have gone to the film festivals with this film for years, a lot of people who were not gay came up to me, even really conservative people and said, “You know, you made a love story and I get it.”

Posted on August 28, 2014 at 5:59 pm

Love is strange. As this movie opens, a deeply devoted couple of more than three decades wakes up and prepares for a big, important, emotional, happy occasion. They bicker a little bit, but it is clear to them and to us that these are reassuringly familiar rhythms for them, almost a contrapuntal love duet in words. Later in the film, two people who admire and care for each other deeply but are getting on one another’s nerves, converse in terms that are genuinely thoughtful and polite, and yet it is clear to us and to them that they are seconds short of wanting to throttle each other. One of them will tell his husband in a phone call, “When you live with people, you know them better than you want to.” That is, unless you share a true, romantic love. That’s what’s strange — how it is that other people’s quirks that would annoy us if we spent too much time together somehow seem endearing when it is someone you love. Love is what makes us not strange to the special people who truly understand us.

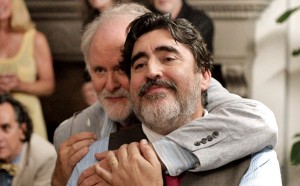

John Lithgow and Alfred Molina play Ben and George, a comfortable but far from wealthy couple who have lived happily together in New York, in a life rich with art, culture, friends, and family. Ben is an artist. George is a choir leader in a Catholic school. As the film opens, it is their wedding day. Gathered in their apartment afterward, they are toasted by their loved ones, including Ben’s niece-in-law, Kate (Marisa Tomei), a writer, who makes a beautiful speech about how seeing them together, when she was dating their nephew, showed her what a loving partnership could be.

But their marriage is too much for the bishop who oversees George’s school, and he is fired. Ben and George go into financial free-fall. They can no longer afford their apartment, and they call on their friends and family to help them while they try to find something less expensive. Everyone wants to help, but this is New York, where space is very limited, and no one can take them both. (A niece who lives in a large house in Poughkeepsie keeps offering, but no one considers that an option.) Ben goes to stay with his nephew, a harried documentary filmmaker, and his wife, Kate, and their teenage son, Joey (Charlie Tahan). He will be sleeping in Joe’s bunk bed. George will be sleeping on the sofa in the small apartment of friends, another gay couple, both cops, who have an active social life.

What “Brokeback Mountain” did to convey that movie romances between gorgeous, glamorous movie stars do not all have to be heterosexual, this film does even better for showing us that the real love story is the one that stretches over decades. Lithgow and Molina exquisitely capture the intimacy and interdependence that only those in very long-term relationships understand. They lightly touch on past disappointments, even betrayals. They tenderly support one another’s vulnerabilities.

The brilliant timing and wit of the scene where Kate is trying to get work done while Ben is cluelessly trying to be a good guest by making social chit-chat is a highlight. Tomei is outstanding, as always. Tahan is marvelously open as a good kid who understandably feels crowded to have a 70-something uncle in his bunk bed. Writer-director Ira Sachs has enough respect for his characters and his audience to allow everyone to be nice. There are no bad guys here (except for the off-screen bishop). But that just makes clear how precious those moments are when we experience the love of those to whom we are never strangers.

Parents should know that this movie is rated R for language only. There is a sad death.

Family discussion: What would you advise Ben and George to do? This movie shows small moments many movies overlook and skips the big moments many movies would include – – why?

If you like this, try: writer/director Ira Sachs’ other films, including “Married Life,” and the classic 1937 film Make Way for Tomorrow.

Posted on August 24, 2014 at 8:00 am

It’s hard to imagine that there will be a more tender love story on screen this year than John Lithgow and Alfred Molina in “Love is Strange,” from writer/director Ira Sachs. They play a long-time couple who get married after decades together but then end up living separately when they can no longer afford their apartment.

It’s hard to imagine that there will be a more tender love story on screen this year than John Lithgow and Alfred Molina in “Love is Strange,” from writer/director Ira Sachs. They play a long-time couple who get married after decades together but then end up living separately when they can no longer afford their apartment.

One of my all-time favorite interviews was with Sachs for his film, “Married Life,” so I was doubly thrilled to have a chance to talk to him about this bittersweet new film.

I love opening scene, as the couple wakes up and engages in the kind of shorthand bicker/banter characteristic of a very long-term relationship. How did you capture that?

I would say that the film was inspired by a lot of different couples, including my mother and stepfather who have been together for 43 years. And just being around her, that fundamentally works and that they still love each other and they’re wonderful partners to each other. But it’s real, so it’s imperfect and it has all the momentary challenges of living an intimate life with someone. That is a big inspiration for me. And also John and Alfred and their own years of marriage. I think that’s where they found their deepest resonance in terms of the characters in their own lives.

One thing that I like about the story is that everybody’s nice. There are conflicts, but there’s no bad guy in the movie.

Robert Altman is a very big inspiration for me and also novelists like Henry James, .people who actually try to look with empathy to everyone in their world. I am what you could call a very democratic director. And to me that’s kind of my job which is to be understanding of people and to be attentive to their foibles and their uniqueness. The more that I position myself like that as a director of the more depth the work can have.

John Lithgow plays an artist, a painter, whose work is representational, rather traditional.

My great uncle in Memphis when I was growing up, he had a partner, and they were together for 45 years. His partner was a sculptor who lived to be 99. I was very close to him in the last ten years of his life. I had to grow up to be old enough to be allowed to be that close to someone of that generation. And he was a man who was working on his last sculpture when he was 98 and it was of a young teenage boy with a backpack. His whole life he always did classical, religious narrative pieces. And suddenly at 98 he was working on something very contemporary about youth. That piece remains unfinished. It’s in clay in a glass at a cousin’s house. I was very inspired by that piece. And the sense of man who or of anyone who is living their life to the fullest for as long as possible and with an openness to new things. And I was actually thinking about this said the other day as I was doing a Q&A with John Lithgow who this summer is doing “King Lear.” He’s a passionate reader, he writes children’s books, he paints, I’ve grown to be very inspired by John which is not something I knew when wrote Ben, but it’s what I hoped for and I think we have to create our models sometime. He’s very funny and he’s got humility and confidence and I think those are both very important quality to be an artiste.

Talk to me about Joey, the teenage son of Ben’s teenage relatives. It was such an interesting choice to end the film on him.

To me it’s film very much about the seasons of life and generations and the circular nature of our time on earth. This film is centered on an older couple but you could also call it a coming of age film. And it’s a film about family, however that is defined. To me it is defined both personally and romantically but also communally. And I think that’s something that I hold on to. I wouldn’t be a filmmaker without my communal family. I wouldn’t think of my last two films without finding a new way that is disconnected from the Hollywood system. As an artist I returned to my independent models like John Cassavetes, the guy who was never given the right to make the films he made but grabbed them when he could. In order for my career to be sustained I had to go back in my mind to when I was young. A lot of what happens for filmmakers particularly is they expect the system to work for them and in terms of these kind of films, that’s not how it happens.

How did the financing come together for this?

Twenty five individuals who responded to the script. You know my last film Keep the Lights On was financed by 400 individuals so at this point I’m talking about a little bit of a different model because it’s 25 instead of 400. But it’s still a group of individuals who understood the power of the story. Since we’ve made the film three of the women who were key investors of have gotten married to their long-term partners. All of them were successful business owners, which is why they were able to invest in my film and I think they understood the inherently human quantity of the story.

One of the great powers of the movie that it’s just a relationship that everybody can relate to. Other than one thoughtless but not bigoted comment from a teenager, the fact that the couple is gay is not significant.

For me as a gay person I cannot be defined as that alone. As an artist, I’m trying to understand character in all its complexity so you can’t put one adjective in front of the other. So that is why I hope that I represent people who are fully human. What we’re trying to do, and this is why a film like “Manhattan” and “Hannah and her Sisters” and particularly, “Husbands and Wives” most of all were very inspiring to us because I think what you try to do is get the details right. We’re not all the same but Shakespeare is still relevant for a reason. Humanly we’re all driven often by the same needs.

One of the stand-out scenes in the film is when Lithgow and Marisa Tomei are in the same room while she is trying to work and also to be polite when he wants to chat. You feel her irritation and yet you see both sides. It is heartbreaking but also very funny!

I have the benefit of working with actors I was initially interested in because of their dramatic chops but what I also had were actors train in comedy. I really noticed it when we were working on that scene. Their timing was just so excellent, and it’s kind of brilliant. And those abilities are what give the film its lightness because it talks about things that are very serious and they are dramatic but I think there’s lightness to that these actors bring and then I hope that I bring. I’m lighter than I was the last time I saw you. I mean “Married Life” was a darker film. And it’s a film about what is hidden. And that was something that was very compelling to me until I was forty.

That is a dark film. It’s about adultery and a husband who plans to commit murder. But it ends in a remarkably sunny way.

We’re all generally struggling lovely people. If you get down to it there’s something touching about each of us. I don’t believe in evil, I believe in the creation of evil.

There’s a very tender scene in “Love is Strange” where we get a glimpse of how sweetly this couple support each other.

They loved each other and they believed in each other. There was a Hal Hartley film made in the 90s called “Trust.” I haven’t seen it since then but I remember one of the characters said that love equals respect plus admiration plus trust. And I’ve actually often thought about those three terms as how they intertwine and how they’re also distinct. The respect is different than admiration and trust is yet another thing. And I’m in a marriage that has those things. But marriage is a legal vessel that this film speaks to but it’s actually not the subject of this film. The subject is intimacy.