There is a thoughtful article in the New York Times by film critics A.O. Scott and Manohla Dargis about the way that on-screen images of African-Americans in the last five decades have reflected and influenced the way race is understood in this country.

Make no mistake: Hollywood’s historic refusal to embrace black artists and its insistence on racist caricatures and stereotypes linger to this day. Yet in the past 50 years — or, to be precise, in the 47 years since Mr. Obama was born — black men in the movies have traveled from the ghetto to the boardroom, from supporting roles in kitchens, liveries and social-problem movies to the rarefied summit of the Hollywood A-list. In those years the movies have helped images of black popular life emerge from behind what W. E. B. Du Bois called “a vast veil,” creating public spaces in which we could glimpse who we are and what we might become.

Make no mistake: Hollywood’s historic refusal to embrace black artists and its insistence on racist caricatures and stereotypes linger to this day. Yet in the past 50 years — or, to be precise, in the 47 years since Mr. Obama was born — black men in the movies have traveled from the ghetto to the boardroom, from supporting roles in kitchens, liveries and social-problem movies to the rarefied summit of the Hollywood A-list. In those years the movies have helped images of black popular life emerge from behind what W. E. B. Du Bois called “a vast veil,” creating public spaces in which we could glimpse who we are and what we might become.

Filmmakers as diverse as Charles Burnett, Spike Lee and John Singleton have helped tear away that veil, as have performers who have fought and transcended stereotypes of savagery and servility to create new, richer, truer images of black life. Along the way an archetype has emerged, that of the black male hero, who, like Will Smith in “Independence Day,” rises from the ashes — in the case of that movie, the smoldering ashes of the White House — to save the day or just the family vacation. The movies of the past half-century hardly prophesy the present moment, but they offer intriguing premonitions, quick-sketch pictures and sometimes richly realized portraits of black men grappling with issues of identity and the possibilities of power. They have helped write the prehistory of the Obama presidency.

They go on to discuss archetypes ranging from Sidney Poitier’s roles as “a benign emblem of black power” to “not-so-benign emblem(s) of black power, erotic and otherwise, the hypersexualized black male (who) also became fodder for white exploitation” like Sweet Sweetback and Superfly all the way to the predatory cop played by Oscar-winner Denzel Washington in “Training Day.” They also identify the “Black Provocateur” played by Richard Pryor or Eddie Murphy and the “Black Father,” a kind of safe harbor for former provocateurs like Murphy, Ice Cube, and Bernie Mac.

Movie history is littered with the mangled (Joe Morton in “Terminator 2”), flayed (Mr. Freeman in “Unforgiven”) and even mauled (Harold Perrineau in “The Edge”) bodies of supporting black characters, some sacrificed on an altar of their relationships with the white headliners, others rendered into first prey for horror-movie monsters. There has often been a distinct messianic cast to this sacrifice, made explicit in films as different as the 1968 zombie flick “Night of the Living Dead” and the 1999 prison drama “The Green Mile.” In the second, Michael Clarke Duncan plays a death-row inmate who suggests a prison-house Jesus: “I’m tired of people being ugly to each other. I’m tired of all the pain I feel and hear in the world every day.” More recently, Will Smith picked up the mantle of the Black Messiah in four of his star turns: “The Pursuit of Happyness,” “I Am Legend,” “Hancock” and “Seven Pounds.”

Savior, counselor, patriarch, oracle, avenger, role model — compared with all this, being president looks like a pretty straightforward job.

James Earl Jones played the first black President in “The Man” in 1972, written by “The Twilight Zone’s” Rod Serling. Even in a fantasy, it was so unthinkable that he could be elected or supported by the American people that the film has him become President only because the President and Speaker of the House are killed in a building collapse, and the Vice-President is too ill to serve. And most of the movie is his struggle to be a leader for both black and white Americans.

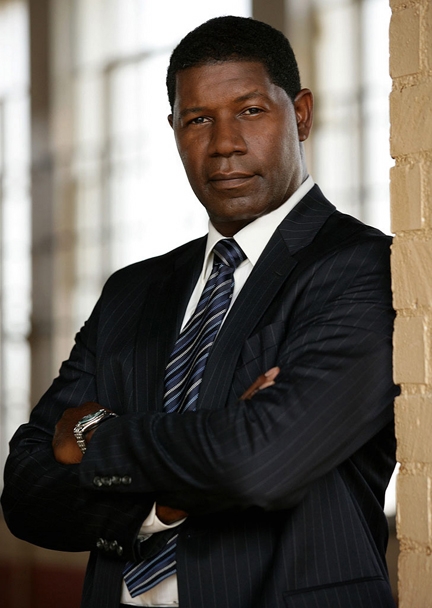

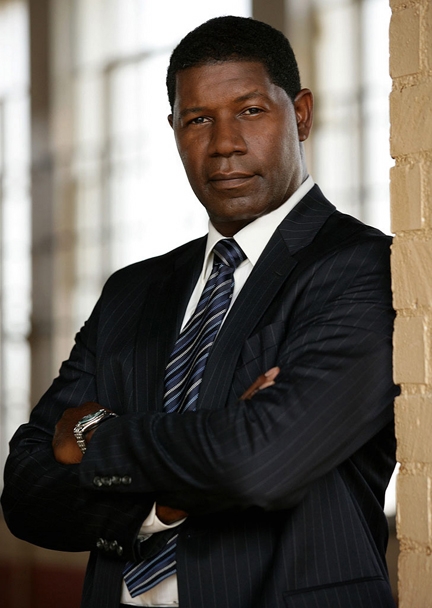

More than 30 years later, Dennis Haysbert played a confident and commanding President on the television show “24.” Like the President played by Jones, he is targeted in an assassination attempt but it may be as much a function of his being a character in a television series about terrorism as it is related to race.

Gawker’s list of seven movies featuring black Presidents has films ranging from satire to sci-fi, played by actors from Terry Crews to Morgan Freeman. Now that it is no longer hypothetical or symbolic, it will be fascinating to see the way that this administration influences future Presidential portrayals. And what will future movie and television Presidents do to suggest the changes ahead? “24” now has Cherry Jones as a female President….

, an epic adventure that takes them to the moon, to be released on DVD . Moving at warp speed, dodging asteroids and more, the Buddies and their two new friends, Spudnick, a sweet bull terrier and Gravity, a resourceful ferret, must summon their courage and ingenuity to launch plans for a moon landing and a rocketing trip back home. Will they have the right stuff?

DVD! I’ll send one to the first three people to send me an email at moviemom@moviemom.com with “Space Buddies DVD” in the subject line.