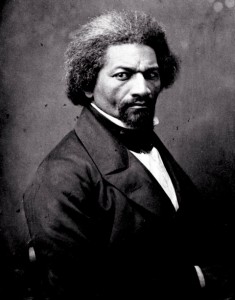

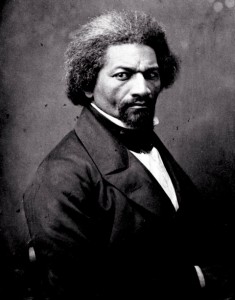

The new release from the PBS series “The American Experience” is a three-part story called “The Abolitionists,” the story of the fight to end slavery in the United States. They were called radicals, agitators, and troublemakers. They thought of themselves as liberators. Men and women, black and white, Northerners and Southerners, poor and wealthy, these passionate anti-slavery activists fought body and soul in the most important civil rights crusade in American history. What began as a pacifist movement fueled by persuasion and prayer became a fiery and furious struggle that forever changed the nation. Bringing to life the intertwined stories of Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, Angelina Grimké, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and John Brown, “The Abolitionists” takes place during some of the most violent and contentious decades in American history. It reveals how the movement shaped history by exposing the fatal flaw of a republic founded on liberty for some and bondage for others. Despite opposition and abuse, beatings, imprisonment, even murder, abolitionists held fast to their cause, laying the civil rights groundwork for the future and raising weighty constitutional and moral questions that are still with us today. “The Abolitionists” interweaves drama with traditional documentary storytelling, and stars Richard Brooks, Neal Huff, Jeanine Serralles, Kate Lyn Sheil, and T. Ryder Smith, vividly bringing to life the epic struggles of the men and women who ended slavery.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xU3RSqT76ic

I spoke to one of the historians who worked on the series, Dr. Manisha Sinha, Professor of Afro-American Studies and History at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

How did you get involved with this program?

I’m in the process of finishing a big book on the history of abolition from the revolution to the civil war. I was tapped for this series to be consulted on the script and be a sort of talking head for it.

One thing that I think is very hard for contemporary people to understand is that even among those who wanted to end slavery, there were many different kinds of views on the reasons for abolition.

Right at the outset it is important to distinguish between people who are sort of anti-slavery, who did not like the system of slavery for a variety of reasons, but who choose not to do much about it, versus the abolitionists, who devoted their lives to fighting against slavery. If you want to look at the roots of the movement, you could go back to the Revolutionary era. There were some outstanding Quaker individuals and African-Americans who fought for abolition and founded some early abolition societies, which resulted in emancipation in the North.

The people who we call abolitionists, they are the ones who came on in the antebellum period, which was 20 or 30 years before the Civil War, when you had people like William Lloyd Garrison, whose publication of The Liberator in 1831 is seen as the starting point of the formal abolition movement in the United States. Garrison of course, owed his inspiration to many of these early Quaker abolitionists, one of whom he served under as an apprentice.

Most importantly, he was very influenced by the black tradition of protest against against slavery and racism. That’s really important to remember. Garrison rejects the idea of Jefferson and later on even Lincoln, which was anti-slavery but wanted to colonize black people outside the United States. What’s unique about Garrisonian abolitionists is that they adopt the African-American program of anti-colonization and black citizenship. If you looked at the roots of Garrisonian abolition, it very much lies in a long tradition of black activism of rejecting colonization and citizenship in this country. To that he adds what is known as Immediatism, which is the immediate abolition of slavery.

That’s when the movement starts taking off in the 1830’s that’s inspired by British abolitionists, who first came up with the idea of Immediatism. It’s inspired by these early outstanding Quakers who fought against the African slave trade and slavery supplemented by this long standing black tradition of protest that had its roots during the Revolutionary era.

I’ve always been very interested in the Grimké sisters. They were pioneering feminists as well as promoters of the abolition of slavery. To me that speaks to a very modern view of equality.

It does. In fact, you could say the abolitionists were well ahead of their time, because they’re fighting not just against slavery, but also racism. They fight against racial discrimination in the North and then they fight for women’s rights. Now of course, that becomes one of the issues that fractured the abolition movement. There were many varieties of abolitionists. You had the Garrisonians, who were fairly radical in their rejections of all kinds of hierarchy, gender and race. You had Evangelical abolitionists, who really didn’t want to mix the question of women’s right with abolition. They thought they had one unpopular cause. They didn’t want to advocate another. Many of these abolitionists were also clergymen.

There were evangelical clergymen, who opposed having women stand up and speak in public like the Grimké sisters, most famously. Of course, before that, an African-American women, Maria Stewart, had done that. And before her, Fanny Wright who was an abolitionist and a workingman’s and women’s rights advocate had spoken out in public to what ware known as “promiscuous” audiences that included both men and women. These are the issues that started dividing the abolitionists.

By the end of the 1830s, we have different varieties of abolitionism. Some of these abolitionists became political abolitionists. Unlike Garrison, they felt that they could work through the political system to abolish slavery. Garrison saw the system that was very dominated by slave holders and by the Northern allies and realized that the fight for abolition would be a long and difficult one. He sort of said that the way for abolitionists to go politically was to agitate in the streets rather than to become part of political system that was corrupt.

The series emphasizes the economic basis of the pro-slavery advocates. It was less a matter of philosophy than it was of money.

Exactly. There were a whole bunch of revisionist historians of the Civil War, who said, “The Civil War was not really a war about slavery. It was about the industrial North against the agrarian South. It was really economic interests that were divergent.” That is true that, that slavery gave rise to a distinct society in the South. In fact, the economic interests of Southern slave holders were quite complementary and in fact linked with that of Northern economic elite.

The people who started attacking abolitionists first were what we call “gentleman of property and standing.” Prominent leaders and the Democratic party were that time leading heavily toward the south. Also, economically others, including the lawyers and politicians, these are the people who led mob violence against abolitionists because they saw abolitionists as threatening these unions, these alliances between Northern capitalists and Southern slave holders.

The people who started attacking abolitionists first were what we call “gentleman of property and standing.” Prominent leaders and the Democratic party were that time leading heavily toward the south. Also, economically others, including the lawyers and politicians, these are the people who led mob violence against abolitionists because they saw abolitionists as threatening these unions, these alliances between Northern capitalists and Southern slave holders.

A lot of work needs to be done on this, but we know that slavery was sort of a national economic interest. Slave-grown cotton was the largest item of export from United States before the Civil War, and its values exceeded the value of all other items of exports from this country, so this was a huge national economic interest that involved Northern banking, insurance, shipping.

It also involved Northern manufacturers. The textile mills at Lowell were dependent on slave-grown cotton from the South. Northern manufacturers of clothes, tools, shoes, found a market in the South. Economically, the North and South had complementary economies, not economies that were in conflict. These are the odds the abolitionist faced. Slavery was entrenched in the nation’s political institutions, it was an enormous part of the nation’s economy. To fight against that made the abolitionists seem like radical fanatics who are advocated women’s equality which was unheard of. They were really taking on big causes and they were fighting against the enormous odds.

Was the abolitionist movement really the first big American political initiative coming from the people? Did it inspire later movements like the civil rights, the women’s movement, the labor movement, anti-war protests, and other reforms?

That’s a great question. Abolition was the first truly radical social movement in this country. It was one of the first to be successful. It became a model for radical activists in later ages. Civil rights activists many times called themselves The New Abolitionists and called for a second reconstruction of American democracy referring back to Reconstruction after the Civil War. Women’s Rights, Second Way Feminism clearly had most of their heroines in this 19th century movement for women’s rights.

It is true that there are a lot of divisions within abolition and within women’s rights during the Civil War over issues of black suffrage and female suffrage. But the fact remains ideologically, the abolitionists remain a source of inspiration. Even Eugene Debs, the head of the American Socialist Party, often pointed to the abolitionists as his inspiration. There were some populists in the Midwest, who looked up to the abolitionists, too. The abolitionists became a kind of a touchstone, because they are one of the few radical movements in this country that was actually successful at the end.

My husband and I stood in line for two hours on New Year’s Day, the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, to get a rare glimpse of it at the National Archives. We have to remember it did not free all the slaves, though it was a very important step.

The Emancipation Proclamation was an official document, a legal document, a military document, born in the midst of war. Its scope was modest, mainly because Lincoln wanted to issue a proclamation that could not be challenged Constitutionally. He invoked his war powers to free the slaves only in the states that were in rebellion, because that’s what he could Constitutionally do as President.

Everyone knew that if the Union won the war, slavery would be dead in Mississippi and in Louisiana and South Carolina. If slavery was dead in those regions, there was very little chance that it could survive in the border slave states that were still in the Union and were not included in the purview of the Emancipation Proclamation. They had far fewer slaves and Lincoln had been pushing them on compensated emancipation since the start of the war.

The idea that it was not momentous, I think is false. Yes, its purview was demarcated for specific reasons, but the Emancipation Proclamation was a turning point in the war. It clearly linked black freedom with the powers of the federal government and the fortunes of the Union army. In many respects, it was actually quite a revolutionary doctrine. No less a person than Karl Marx said that it made the Civil War into a revolutionary war for freedom.

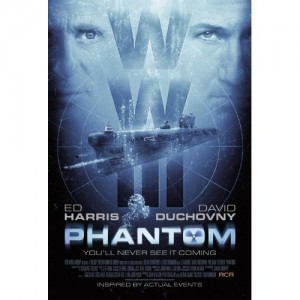

Submarine movies are immediately gripping because they are powerful microcosms that amplify conflict. A small group of people in very close quarters, highly trained and with an explicit mission are then completely disconnected from the rest of the world. When problems arise, they have to decide what to do with very limited information and no access to authority outside the ship. Great drama, when it works. This time, though, not so much.

Submarine movies are immediately gripping because they are powerful microcosms that amplify conflict. A small group of people in very close quarters, highly trained and with an explicit mission are then completely disconnected from the rest of the world. When problems arise, they have to decide what to do with very limited information and no access to authority outside the ship. Great drama, when it works. This time, though, not so much.