Henryk Hoffmann on Hollywood Legends in Literature

Posted on July 12, 2016 at 3:49 pm

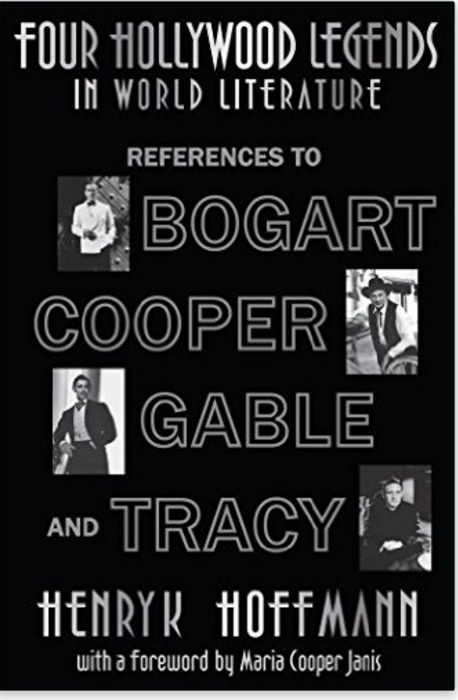

Henryk Hoffmann’s Four Hollywood Legends in World Literature: References to Bogart, Cooper, Gable and Tracy is an extraordinary resource, grounded in massive research and filled with insights about the way four iconic Hollywood figures have inspired and influenced an astonishing range of literary and creative works. In an interview, Hoffmann described the qualities that made Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart, Gary Cooper, and Spencer Tracy uniquely influential, and the ways that their lives and their work were reflected in books by writers from Larry McMurtry to Elmore Leonard.

What is it about these four men that makes them such timeless and iconic figures?

Each of them possessed a rare kind of charisma, each developed an unusually attractive and appealing persona and each appeared in an impressive number of outstanding, essential (for one reason or another) and unforgettable films. And, of course, we must not forget about the great acting talent with which each of the four men was—in a varying extent—endowed. If you feel that the same can be said about some actors of the younger generations, then I would have to refer to the sociological and cultural criteria that clearly define the times of Bogart, Cooper, Gable and Tracy as something absolutely unique in America and in the world, the times of magic nonexistent ever after.

What would you say are the distinctive qualities that make them so appealing to authors and the characters they create?

It is closely related to the previous question. Most of the authors that have (intentionally, I assume) mentioned one of the four names in their works of fiction are quite aware that a certain legendary or mythological qualities would be automatically entailed, understood or evoked by any reader even remotely familiar with the history of the American cinema. Why? Because the collective or individual image of those four movie stars, either as symbols of the great American hero or as foremost examples of the Golden Era of Hollywood, prevails in the mentality of the devoted moviegoers—certainly those contemporary with the actors, but also those representing younger generations, which is proven by the age of numerous authors quoted in my book.

What are the most frequent uses of references to these stars in literature? As metaphor or as historical/cultural context?

The references discussed in my book play a variety of roles in literature, including those that you mention in your question. It is almost impossible to recount all types, but I tried to categorize/classify them in the Epilogue, where I list thirty-one different uses along with my favorite examples of each. In terms of frequency or any other statistics, it would take a separate time-consuming study to find out which types are most common in literature and which are rather rare or accidental.

How do references to the performances differ from references to the actors themselves?

When an actor’s name is mentioned together with a title of one of his films, the reference usually pertains to a specific scene or the storyline of that movie. A rare (and nice) exception is the reference to Gary Cooper and Mr. Deeds Goes to Town in Elliott Roosevelt’s Murder in the Red Room, where the purpose of the allusion is to emphasize the perfect match between the actor’s persona and the character he portrays. On the other hand, when an actor is mentioned without any movie title, then the purpose of such a reference is usually to capitalize upon his status or prestige as an actor or celebrity.

Do you think that today’s more intrusive, more omnipresent, and less managed presentations of actors’ personal lives in the media will prevent literary use of contemporary stars in the same way these four legends were used?

I would not like to sound prejudiced, but my research points out that references to younger generations of actors (including those with careers longer than Bogart’s or Cooper’s) are by far less numerous, with a pattern showing almost nonexistent interest in the actors of the very young generation, anyone born after 1960. I said “almost,” because I did find some references to Tom Cruise and the like, but they tend to be clearly less complimentary, less positive, sometimes even derogatory. I have my own theory about this phenomenon, but I do not think this is the place to reveal it.

Your work is remarkably comprehensive but there are no databases for these references. What kinds of resources did you use for your research?

Right! There is no database; I have been building it as a pioneer. It started a long time ago when I read books like From Here to Eternity, The Blackboard Jungle, The Catcher in the Rye, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? and several others, where I noticed the first movie references in fiction and decided to record them for no particular reason. Sometime later I discovered Larry McMurtry with his numerous and rich allusions, but the writer who gave me the idea of turning the data into a book was Elmore Leonard. Since both McMurtry and Leonard, but also some other favorite writers of mine (such as John Updike, Robert B. Parker, Lawrence Sanders, Loren D. Estleman and Tim O’Brien), frequently allude to westerns, my first book on the subject (published by McFarland in 2012) was Western Movie References in American Literature. Upon completion of that book I already had a substantial data base for my next project on references (to the four legends, tentatively), but my subsequent research (based primarily on intuition) expanded it to unexpected proportions. Thus, I had no doubt who it should be focused on. I got in touch with two children of the famous actors and received blessing, guidance and support from Maria Cooper Janis and Stephen Humphrey Bogart.

What movie role is referred to most often in literature?

Two films, Gone with the Wind and Casablanca, have accumulated the biggest number of references (both mentioned in more than 100 works). However, the focus of those allusions is spread over a number of characters, scenes and themes. Consequently, it is Gary Cooper as Marshal Will Kane that gets most attention from writers, and it is the scene of Coop walking tall while looking for help in High Noon (referenced in eighty-one works) that is most frequently mentioned in books. By the way, that particular image was used on the side of the Gary Cooper postal stamp issued in 2009 in the “Legends of Hollywood” series, and, before that, in the Polish post-World War II first free-election poster designed by Tomasz Sarnecki in 1989. The cover of “Gazeta Wyborcza” (Poland’s foremost newspaper) of June 6, 2016, with Sarnecki’s poster announcing an extensive article on the 27th anniversary of the election, can be treated as one more vivid reminder of the incredible impact of one of the Four Hollywood Legends outside the movie world.

Do you have a favorite literary reference to one of these legends or performances?

Here I would like to refer again to my list of 31 items in the Epilogue. All those references are special to me. I have a hard time choosing one, but if I were to pick out three, I would say #13 (Distant Drums referenced in McMurtry’s All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers—most vivid), #15 (High Noon referenced in Martha Grimes’s The End of the Pier—most personal) and #31 (Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner referenced in Herman Koch’s The Dinner—most complex and informative).