No Place on Earth is the extraordinary new documentary about a small group of Jews from Ukraine who hid from the Nazis in two caves for almost two years. Interviews with the survivors, narration from a book written in the 1960’s by the woman who was one of the leaders of the group, some re-enactments, and a powerful return to the caves 67 years after the end of the war. Tonight, as the annual observance of Yom Hashoah, the day of holocaust remembrance, it is especially meaningful to share this story.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n00EE5CeatA

I spoke to director Janet Tobias about making the film.

One of the people in the film says, “We were not survivors. We were fighters.” What do you think that means?

They were fighters. They stuck together. Esther Stermer was an incredible mother and grandmother, a matriarch. She didn’t do the obvious thing. She decided to do what was necessary to survive and to protect her family. It’s an incredible story of what they accomplished. The lesson I take away from it is how much we depend on each other. they were greater as a collective whole than they were individually. Many of them would not have made it on their own. We do much better when we have each other than on our own.

The families were extended families, but it was a tough world. There had to be a group of people from each family who were willing to risk their lives on a weekly basis.

Tell me about the re-enactments of some of the scenes, which you shot in Hungary.

I was blessed with an incredibly great group of Hungarian actors, from Kati Lábán, who played Esther Stermer who is a very well-known actor in Hungary to some who had never acted before. We looked for approximation of physicality but I was not going to be completely literal because it is more important to have the person who has the right understanding of the story and the spirit. We did recreations, a hybrid between documentary and drama, because on the one hand you are in the presence of the last years of people who were eyewitnesses, who can say, “That happened to me. I saw it,” which is an incredible gift in documentary. On the other hand, the Stermers were fighters, as you said. They were actors on their environment. Lots of documentaries are about people contemplating their life. But the Stermers were fighters, not contemplators. They are doers. To show the incredible thing they accomplished, what they got up and did, that needed actors. Esther Stermer had a clock in her head. She kept a cooking schedule, a cleaning schedule. They knew when they could go out without moonlight. They observed the holidays. When they were buried alive, they did not give up and say “It’s over.” They said, “We need to do the following things in construction to even have a chance of figuring this out.” They were dramatic actors in real life, so we needed to match that.

And we had to show what it was like to live in the cave. I had never been in a cave except to walk by the opening on a hike. That world is a crazy strange world, the claustrophobic spaces, the mud, the darkness. It’s really hard to imagine, so we really needed to show people the world they were living in and navigating in, the world they ultimately found safer than the outside world.

You can see how dynamic they still are when they return to the cave, 67 years later. They were so young when they were in the cave.

You do hear Esther’s words in the book she wrote in 1960. And the leadership in the cave passed to young men. It shows how incredibly brave and honorable young men can be. Esther was running things underground but the father was afraid and so the leadership in the cave was teenage boys and young men in their 20’s because they were capable of doing things that kept everyone alive.

The story of the horse is almost like a fairy tale, especially when the families, who are so hungry, decide not to eat the horse but to let him go.

Even Sol did not believe his brother would come back with a horse. For Sol, it was this miraculous thing for his brother to find a horse to help them get supplies. They felt so blessed and lucky that they did not eat the horse.

And when they returned, no one in the town even said hello to them.

After the war, fighting continued in Ukraine. Partisans were fighting the Russians. Their possessions were taken by people who did not want to give them back. There was a lot of hostility to Jews, which is why there are no Jews in that town anymore. Their dog gave them the only greeting. We really wanted their return to be meaningful for them and it was. They are very special people.

Why was it important to show the photographs of the families of the survivors at the end?

What these 38 people did, each with individual experiences, each fighting hard, from the children to the grandparents — the ripple effect is life. All the children and grandchildren and great-children who became lawyers, doctors, construction workers, physical therapists, they are all alive because these people fought. Fighting and survival and preventing genocide, that starts one person at a time. One Polish woodcutter giving information, one person saying “We’re not going to leave our cousin behind,” that has a ripple effect of life with generations who make a difference.

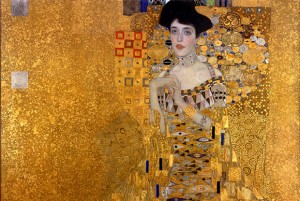

, Stealing Klimt, and The Rape of Europa

. “The Woman in Gold,” a new feature film about the lawsuit with Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds, will be in theaters this spring.