Trailer: Sharknado 3

Posted on June 6, 2015 at 8:00 am

Posted on June 6, 2015 at 8:00 am

Posted on January 23, 2015 at 9:36 am

There’s a lot of noise in “Mortdecai” but what I remember most is the silences where everything pauses for a moment to allow the audience to laugh without drowning out the next witty riposte. Nope, just crickets, as there was no laughter, just grim resolve on the part of those of us professionally obligated to stick it out through the bitter end.

“Mortdecai” is based on series of 1970’s comic novels by Kyril Bonfignioli about an art dealer with connections to the upper class and the criminal underground, which provide him with many opportunities for mischief. I’m sure they are all high-spirited and merry and racy and fun, but by the evidence of this film they are also dated, overly precious, and not susceptible to translation into film. Perhaps it was possible decades ago and in print rather than on screen to find it funny when someone is repeatedly shot and injured, often accidentally by his employer, or when someone else is shot and killed. But not now and not like this.

Maybe gag reflexes brought on by Mortdecai’s mustache and widespread barfing brought on by tampering with a sumptuous buffet can be funny when left to the imagination. Not likely, but clever writing might just make it possible as our imaginations are very good at filtering descriptions according to our comfort levels. It’s another thing entirely when it is unavoidably seen and heard. Cue the crickets.

Over the past few years, with the exception of a brief appearance in “Into the Woods” Johnny Depp has made one catastrophically bad movie after another. As proof of the adage that no good deed goes unpunished, the success of his offbeat, fey Captain Jack Sparrow, initially objected to by the studio execs who were very unhappy with the early footage, has given Depp license to go way over the top with quirks and twitches in films like “The Lone Ranger” and “Tusk.” As I noted in my review, in “Transcendence” his performance was so robotic when he was playing a human that it hardly made a difference when he turned into a computer. Here, as the title character, a caricature of a pukka sahib colonial twit/Brit, embodies the fatal combination of profound unpleasantness with the expectation of being seen as irresistibly adorable not just by the other characters but by the audience.

Paul Bettany provides the film’s only bright moments as Jock Strapp, Mordecai’s Swiss army knife of a sidekick, as adept at ironing his lordship’s handkerchiefs as he is at hand-to-hand combat, getaway car driving, anticipating that Lady Mortdecai (Gwyneth Paltrow, looking like the cover of Town and Country in very fetching riding gear) will want the guest room made up for her husband as soon as she sees his new mustache, and bedding many, many, many ladies. Ewan McGregor does his valiant best but is wasted as the Oxbridge-educated MI5 official (and former classmate of Mortdecai, with a crush on Lady M). Director David Koepp, whose “Premium Rush” was a nifty little thriller with unexpected freshness and wit, has stumbled here with a film that is badly conceived in every way, like its title character imagining itself as clever and endearing when in reality it is dull and repellent.

Parents should know that this movie includes strong and crude language, drinking and comic drunkenness, sexual references and situations, some crude, bodily function humor, comic peril and violence including guns, with characters injured and killed.

Family discussion: What was the best way to resolve the issue of the mustache? Who should have the Goya painting?

If you like this, try: The Mortdecai Trilogy and the Austin Powers films

Posted on October 16, 2014 at 5:25 pm

B+| Lowest Recommended Age: | Mature High Schooler |

| MPAA Rating: | Rated R for language, sexual content and drug use |

| Profanity: | Very strong language including racist terms |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Drinking, drug use |

| Violence/ Scariness: | Tense confrontations |

| Diversity Issues: | A theme of the movie |

| Date Released to Theaters: | October 17, 2014 |

| Date Released to DVD: | February 2, 2015 |

| Amazon.com ASIN: | B00OMCCJIS |

Before I turn to whitesplaining this film, I will begin by suggesting that you read what Aisha Harris at Slate and what my friends and fellow critics Travis Hopson and Stephen Boone have to say first. If I did not have enough humility before seeing the film about my ability to provide some insight into a movie about racism, the best evidence of the power of the film’s message is that I have more now — and that I recognize it might still not be be enough. I liked the film very much and want to encourage people to see it, so I am going to weigh in with some thoughts and hope that if they come across as disrespectful or ignorant, it will lead to some good conversations and, I hope, to greater understanding.

Before I turn to whitesplaining this film, I will begin by suggesting that you read what Aisha Harris at Slate and what my friends and fellow critics Travis Hopson and Stephen Boone have to say first. If I did not have enough humility before seeing the film about my ability to provide some insight into a movie about racism, the best evidence of the power of the film’s message is that I have more now — and that I recognize it might still not be be enough. I liked the film very much and want to encourage people to see it, so I am going to weigh in with some thoughts and hope that if they come across as disrespectful or ignorant, it will lead to some good conversations and, I hope, to greater understanding.

The focus is on four African-American students at an Ivy League school called Winchester University. Sam White (a biting but layered performance by standout Tessa Thompson) is the host of “Dear White People,” a controversial radio program with stinging, provocative commentary along the lines of “Dear white people: The official number of black friends you are required to have has now been raised to two. And your weed man does not count.” Coco (Teyonah Parris) is an ambitious woman who wants to be selected for a new reality TV series, even if that means creating a fabricated backstory and becoming more confrontational. Troy (Brandon P Bell) is the handsome, accomplished BMOC (and son of the dean) who says he has never experienced prejudice and is under a lot of pressure from his father to succeed. And Lionel (Tyler James Williams) is something of a loner because he feels he does not fit in with any of the rigid categories of the campus hierarchical taxonomy. He is invited by the editor of the school newspaper to go undercover to write about race relations at the school.

Each of these characters’ identities and conflicts is represented in their hair. Sam has tight, controlled coils. Coco has long, straight hair. Troy’s hair is cut very close to the bone. And Lionel’s hair is a marvel of untamed frizz that seems to be a character of its own. Each of the characters will face challenges to his or her carefully constructed identity, and all will be reflected in changes of hairstyle.

The dorm that had previously been all-black is now integrated following a race-blind room assignment policy. Sam takes on Troy in an election for head of house, never anticipating that she might win. But she does. This leads to some changes, including a confrontation with the arrogant frat-bro Kurt (Kyle Gallner), son of the white President of the university and leader of the school’s prestigious humor publication. Kurt is the kind of guy who expects to be allowed to eat wherever he likes, even if he is not a member of the house. He also explains that we live in a post-racial world because Obama is President. And he thinks it is a great idea to plan a “ghetto” party, with white students dressing up as gangsta caricatures.

Just to remind us that, while the movie may have a heightened sensibility for satirical purposes, it is not outside the realm of reality, the closing credits feature a sobering series of photos from real “ghetto” parties held on campuses across the country.

It is refreshing, provocative, and powerfully topical, respecting and updating the tradition of “School Daze” and “Higher Learning.” It deals not only with questions of race but with broader questions of gender, class, identity, and the way we construct our personas, especially in our late teens and early 20’s. Writer/director Justin Simien has created a sharp satire with an unexpectedly tender heart.

Parents should know that this film includes very strong language including racial epithets, sexual references and situations, drinking, drug use, and tense confrontations about race, class, and gender.

Family discussion: Where do the people in this movie get their ideas about race, gender, and class? Which character surprised you the most and why? Do you agree with what Sam said about racism?

If you like this, try: “School Daze” and “Higher Learning”

Posted on September 30, 2014 at 11:06 am

B+| Lowest Recommended Age: | Middle School |

| Profanity: | Some mild language |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Drinking and partying |

| Violence/ Scariness: | None |

| Diversity Issues: | Diverse characters |

| Date Released to Theaters: | September 26, 2014 |

| Amazon.com ASIN: | B00MI506MC |

In his last film, a documentary called “Beware of Christians,” Bakke told the story of his journey with four friends, all from devout Christian families, as they traveled through ten European cities to expand their understanding of what it means to be a person of faith. That experience clearly informs this fictional story of four college fraternity brothers. When one of them discovers that his scholarship has run out with one more tuition payment still due, he persuades his friends to establish a fake Christian charity so they can keep the money. Each of them has a different perspective. Sam (Alex Russell, soon to be seen in Angelina Jolie’s “Unbroken”), is the slick, dimpled operator who thinks this is just the ticket to smooth his path to law school. Pierce (Miles Fisher) is the selfish rich kid who does not want his father to know he is in debt. Baker (Max Adler of “Glee” and “Switched at Birth”) is the party animal who is up for whatever’s going on. And Tyler (Sinqua Walls of “The Secret Life of an American Teenager”) is a nice guy who goes along because they promise he will not have to speak in front of a group and they promise that some of the money will actually go to charity.

Sam is a charismatic speaker and the audience wants to believe. Not only do they raise money quickly for their fake charity (cutely dubbed “Get Wells Soon”), but they attract the attention of a promoter named Ken (Christopher McDonald), who wants to book them on a nationwide tour for Christian audiences. Also on the tour are a singer named Gabriel (“Happy Endings'” Zachary Knighton, with just the right touch of oily smugness) and the tour manager (and Gabriel’s girlfriend) Callie (Johanna Braddy). The guys have to up their game to appear to be more authentic. They don’t just use highlighters and post-its to mark Bible passages, they baptize their Bibles in swimming pool water to give them that thoroughly-thumbed look. In one of the movie’s highlights, Sam explains to the others how to use certain words and poses (like “The Shawshank”) to communicate piety and get more money from believers, and even how to swear just enough but not too much. Can they immerse themselves in the world of faith — and the evidence of true need — without being affected by it, especially with the example of at least one believer who demonstrates true grace?

Bakke and his co-screenwriter Michael B. Allen bring a lot of specificity to these scenes, and a sensitivity that shows he is laughing with the Christians (especially when it comes to Christian entertainment), not at them. They understand that their open-hearted generosity can be unthinking but is almost always kindly meant. And they understand that being a believer does not inoculate anyone from human failings, especially pride. They also understand that true faith requires the full engagement of the spirit. And they respect their characters and the audience enough to make it clear that the answers we value most are never easy.

Parents should know that this film has some drinking and partying and some criminal and unethical behavior.

Family discussion: Which character best fits your idea of what it is to have faith? What should Ken have done when he found out what the boys were doing? What will Sam do next?

If you like this, try: “Beware of Christians” and films like “Elmer Gantry,” “Jesus Camp,” “Marjoe,” “Blue Like Jazz,” and “Leap of Faith”

Posted on March 13, 2014 at 6:08 pm

B+| Lowest Recommended Age: | Mature High Schooler |

| MPAA Rating: | Rated R for language, some sexual content, and violence |

| Profanity: | Strong and crude language |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Drinking, drugs |

| Violence/ Scariness: | Murder, wartime violence |

| Diversity Issues: | Diverse characters |

| Date Released to Theaters: | March 8, 2014 |

| Date Released to DVD: | June 16, 2014 |

| Amazon.com ASIN: | B00JAQJNN0 |

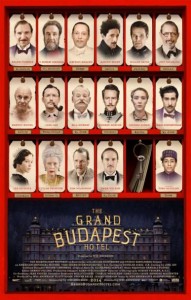

Writer/director Wes Anderson loves precious little worlds and his movies are not just created, they are curated. There’s a reason that this film is named for its location, not its characters or plot. Anderson is the master of “saudade,” the nostalgia for something you never had or that never existed. The Grand Budapest Hotel is as romantically imagined as its name, more vividly realized than any of the human characters in the movie, and we instantly feel the pang of its loss.

Writer/director Wes Anderson loves precious little worlds and his movies are not just created, they are curated. There’s a reason that this film is named for its location, not its characters or plot. Anderson is the master of “saudade,” the nostalgia for something you never had or that never existed. The Grand Budapest Hotel is as romantically imagined as its name, more vividly realized than any of the human characters in the movie, and we instantly feel the pang of its loss.

We enter through a Sheherezade-ian series of nesting narratives. A girl visits the grave of a writer, and we go back in time to see that writer (Tom Wilkinson) as an older man, talking about where writers get their stories (from real life), and then back again further as a younger man (Jude Law), actually getting the story in a bleak, bordering on seedy distressed version of the hotel, from an old man named Zero Mustafa (F. Murray Abraham). And then we go further back in time to see Zero as a young man, a proud lobby boy in the titular edifice, a gorgeously splendid, elegant, and luxurious resort in the mountains of a fictitious European country called Zubrowka, somewhere in the midst of Switzerland, Luxembourg, Austria-Hungary, and the Balkans. Anderson invites us into the artificiality of the memory within a memory within a story told by a stranger. He does not bother with cinematic tricks to make the hotel look real. We see it made out of paper, with a paper finicula pulled by a string to bring the guests up the mountain, as though it is part of a puppet show, which, in a way it is. At times it feels as though it is being put on with the marionettes from the “Lonely Goatherd” number in “The Sound of Music.” There is no effort to make the actors playing the younger and older versions of characters look alike. But the detail work is as meticulous as ever, so that must be intentional, and meaningful.

In the era of the Jude Law storyline, the hotel’s inept concierge is M. Jean (Jason Schwartzman). But, as Zero tells the story, in the heyday of the hotel, the concierge was the legendary M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes). A concierge is there to be the all-purpose fixer, finder, and minder, like the entire staff of Downton Abbey in one. M. Gustave is infinitely attuned to the needs of the hotel’s wealthy, important, often noble (as in duchesses, not heroes), and always demanding clientele. There is a reason they are always referred to as guests. And if they require a particularly specialized and personal form of service, he is willing to oblige, even if the guest in question is a titled termagant in her 80’s (an hilariously unrecognizable Tilda Swinton as Madame D.) Fiennes gives a performance as perfectly precise as his character, whose flawless demeanor evokes exquisite deference, competence, and discretion. Like Anderson and Anderson’s autobiographical stand-in played by Schwartzman in “Rushmore,” M. Gustave is a showman, and one with an extravagantly grand and very ambitious sense of mise-en-scene. Early on, we see M. Gustave striding through the hotel lobby, a gracious farewell to a guest on one side, sharp but not unkind directions to staff who are not up to standard on the other. Later, in two intrusions by this story’s version of the Nazis and later, as a prisoner, he responds as though he is in a drawing room comedy. Fiennes pulls off the tricky balance between farce and drama as the story takes him through murder, art theft, love, war, and delectable pastries. And he is matched by newcomer Tony Revolori as the young Zero, a refugee who aspires to M. Gustave’s savoir faire, and who becomes first his protege and then his friend.

As always in a Wes Anderson film, starting with the very first scene of his first movie, “Bottle Rocket,” there is an escape. M. Gustave is imprisoned, but still strives to maintain an aura of gracious living. After a rough encounter with another prisoner, he is bruised but airily assures the visiting Zero that they are now dear friends. He confronts the direst of situations — or tries to — as though they are at the level of an errant lobby boy. But when he is deprived of his beloved fragrance, L’Air de Panache, he begins to crumble.

The details of the various time periods are, as expected, exquisitely chosen, well worth a second viewing. Ant it is a bit warmer than Anderson’s previous films, less arch, less removed, softer toward its characters, even tender. Anderson often makes objects more important than people but in this one, with the painting and the pastry almost character themselves on one side and Zero and his true love Agatha (Saoirse Ronan) still stylized but still heartfelt on the other, they’re getting closer.

Parents should know that this film includes wartime violence, with characters injured and killed, some graphic and disturbing images, strong language, sexual references and an explicit sexual situation.

Family discussion: Did M. Gustave and Zero have the same priorities? What is added to the story by seeing the author and Zero later in their lives?

If you like this, try: “Moonrise Kingdom” and “Rushmore”