Interview: John Madden of ‘The Debt’

Posted on August 30, 2011 at 8:00 am

John Madden, director of “Shakespeare in Love” and “Proof,” came to Washington, D.C. to talk about his newest film, “The Debt.” It is a remake of an Israeli film about three Mossad agents who are revered as heroes for capturing a Nazi war criminal, who was then killed trying to escape. The film moves back and forth in time between the capture in the 1960’s and 1997, when a book about it, written by the daughter of two of the agents, is published. We spoke about the challenge of casting a villain,

How did you become involved in a remake of an Israeli film?

An agent called Ari Emanuel, the brother of Rahm represents Matthew Vaughn and the producer of the original film. Because it was in Hebrew it did not get a release anywhere else, but they thought it was an interesting project to reconsider or adapt for a wider audience. So Matthew wrote a script that was faithful to the original story but it was structurally a little different. The original film cross-cuts more between the two time frames. He sent it to me, so the first way I came across the material in that form. I thought it a very compelling and interesting story which I immediately wanted to unravel. I did watch the original film — it’s the raw material and I wanted to honor that. But I hoped it would not be very good! It would be easier. But it was good, very arresting. It didn’t daunt me or arrest me. It excited me because I could see it was a very powerful piece. We inevitably developed the story in different ways, with different emphasis. The material is sufficiently strong and charged and complex that as a director you need to find your own way through it.

I’m always interested in what goes into casting the villain, especially in this film where you have an actor who is unknown in the US and who gives a spectacular performance.

Jesper Christensen plays the villain. He’s Danish and fantastically highly regarded and respected actor with a very long list of stage and movie credits. I didn’t want an audience to be able to say immediately, “Oh, here’s the villain.” The preoccupations of the story is about moral responsibility. I didn’t want the ground to be completely solid. One of the things you wonder as the Navy Seals must have wondered as they came into the compound in Abbottabad not knowing if the person there was Bin Laden. You do find yourself thinking even once he’s in captivity, “Have they got the right guy?” He is clever enough to exploit the weaknesses in the scenario to his own advantage. A Nazi doctor is about the apotheosis of villainy in a certain kind of cinematic literature and that’s a trap, a danger of two-dimensionality, and Peter Straughan and I were very conscious of not wanting this character to cooperate with the script, not wanting him to be this monstrous presence. He does say things that are monstrous, but even that you have to contextualize that he’s a man fighting for his life and looking for any advantage. He can be quite charming when he says he would prefer to be fed by Rachel, who had, he says, the makings of a nurse in another life. There’s something beguiling in that sort of wisdom and you find yourself agreeing with him when he says that.

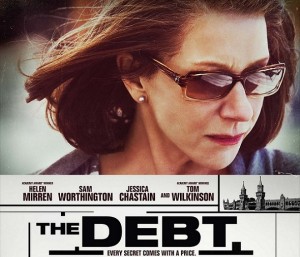

We were under a lot of pressure to change the title at one point. It’s somewhat of a negative signifier in this modern age though I always thought it was a marvelous title. In the interest of collaboration, I said, “Well, if we can come up with another one,” and one we thought of was “Another Life.” He is a man who makes another life for himself, or tries to. Watch for the moment when he starts speaking in English. And there’s Rachel, looking out behind sunglasses which are supposed to protect her eyes from the sun but she’s looking out at a life she should never have had, that is a false life, that seemed a provocative and interesting idea.

It is very Israeli to have such an international cast. Israel is even more of a melting pot than the US.

I’m slightly conscious of the fact that other than the Israeli actors, the principals are not by in large Jewish. That wasn’t by intent. But the internationality of the cast gave me a kind of latitude. I don’t think anyone watching the film would know where Jessica Chastain or Marton Csokas was from. He’s actually half Hungarian. And Jesper is a Dane who blessedly is completely fluent in German and English.

Did you have the actors who played the younger versions of the characters work with the actors who played their older selves?

Only Helen and Jessica. That symbiosis is necessary for the story and I set higher standards of physical affinity. I wanted Jessica to be an unknown but she’s less of an unknown now! I looked at the photos of the men side by side. But David is almost unrecognizable to himself, one of those situations where you might say, “I saw him the other day and you wouldn’t recognize him.” So resemblance was less important.

It is a story about stories, isn’t it?

There’s a lot of thematic richness in the film. It’s about a need for heroes and the way we mythologized them. This country’s whole political discourse and movie culture is based on the idea of the hero. It’s a very potent idea to deconstruct. And we all mythologize our own histories with an unconscious editing of our own behavior. You know you’ve got a good story when it starts talking back to you and revealing things that you haven’t foreseen. It’s the daughter’s unawareness, the way she is enveloped in a lie — the mother has to do something truly heroic, to immolate herself in order to release her daughter from the contamination of the lie.