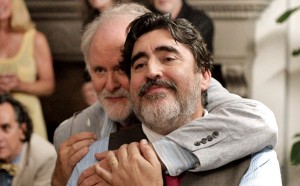

It’s hard to imagine that there will be a more tender love story on screen this year than John Lithgow and Alfred Molina in “Love is Strange,” from writer/director Ira Sachs. They play a long-time couple who get married after decades together but then end up living separately when they can no longer afford their apartment.

It’s hard to imagine that there will be a more tender love story on screen this year than John Lithgow and Alfred Molina in “Love is Strange,” from writer/director Ira Sachs. They play a long-time couple who get married after decades together but then end up living separately when they can no longer afford their apartment.

One of my all-time favorite interviews was with Sachs for his film, “Married Life,” so I was doubly thrilled to have a chance to talk to him about this bittersweet new film.

I love opening scene, as the couple wakes up and engages in the kind of shorthand bicker/banter characteristic of a very long-term relationship. How did you capture that?

I would say that the film was inspired by a lot of different couples, including my mother and stepfather who have been together for 43 years. And just being around her, that fundamentally works and that they still love each other and they’re wonderful partners to each other. But it’s real, so it’s imperfect and it has all the momentary challenges of living an intimate life with someone. That is a big inspiration for me. And also John and Alfred and their own years of marriage. I think that’s where they found their deepest resonance in terms of the characters in their own lives.

One thing that I like about the story is that everybody’s nice. There are conflicts, but there’s no bad guy in the movie.

Robert Altman is a very big inspiration for me and also novelists like Henry James, .people who actually try to look with empathy to everyone in their world. I am what you could call a very democratic director. And to me that’s kind of my job which is to be understanding of people and to be attentive to their foibles and their uniqueness. The more that I position myself like that as a director of the more depth the work can have.

John Lithgow plays an artist, a painter, whose work is representational, rather traditional.

My great uncle in Memphis when I was growing up, he had a partner, and they were together for 45 years. His partner was a sculptor who lived to be 99. I was very close to him in the last ten years of his life. I had to grow up to be old enough to be allowed to be that close to someone of that generation. And he was a man who was working on his last sculpture when he was 98 and it was of a young teenage boy with a backpack. His whole life he always did classical, religious narrative pieces. And suddenly at 98 he was working on something very contemporary about youth. That piece remains unfinished. It’s in clay in a glass at a cousin’s house. I was very inspired by that piece. And the sense of man who or of anyone who is living their life to the fullest for as long as possible and with an openness to new things. And I was actually thinking about this said the other day as I was doing a Q&A with John Lithgow who this summer is doing “King Lear.” He’s a passionate reader, he writes children’s books, he paints, I’ve grown to be very inspired by John which is not something I knew when wrote Ben, but it’s what I hoped for and I think we have to create our models sometime. He’s very funny and he’s got humility and confidence and I think those are both very important quality to be an artiste.

Talk to me about Joey, the teenage son of Ben’s teenage relatives. It was such an interesting choice to end the film on him.

To me it’s film very much about the seasons of life and generations and the circular nature of our time on earth. This film is centered on an older couple but you could also call it a coming of age film. And it’s a film about family, however that is defined. To me it is defined both personally and romantically but also communally. And I think that’s something that I hold on to. I wouldn’t be a filmmaker without my communal family. I wouldn’t think of my last two films without finding a new way that is disconnected from the Hollywood system. As an artist I returned to my independent models like John Cassavetes, the guy who was never given the right to make the films he made but grabbed them when he could. In order for my career to be sustained I had to go back in my mind to when I was young. A lot of what happens for filmmakers particularly is they expect the system to work for them and in terms of these kind of films, that’s not how it happens.

How did the financing come together for this?

Twenty five individuals who responded to the script. You know my last film Keep the Lights On was financed by 400 individuals so at this point I’m talking about a little bit of a different model because it’s 25 instead of 400. But it’s still a group of individuals who understood the power of the story. Since we’ve made the film three of the women who were key investors of have gotten married to their long-term partners. All of them were successful business owners, which is why they were able to invest in my film and I think they understood the inherently human quantity of the story.

One of the great powers of the movie that it’s just a relationship that everybody can relate to. Other than one thoughtless but not bigoted comment from a teenager, the fact that the couple is gay is not significant.

For me as a gay person I cannot be defined as that alone. As an artist, I’m trying to understand character in all its complexity so you can’t put one adjective in front of the other. So that is why I hope that I represent people who are fully human. What we’re trying to do, and this is why a film like “Manhattan” and “Hannah and her Sisters” and particularly, “Husbands and Wives” most of all were very inspiring to us because I think what you try to do is get the details right. We’re not all the same but Shakespeare is still relevant for a reason. Humanly we’re all driven often by the same needs.

One of the stand-out scenes in the film is when Lithgow and Marisa Tomei are in the same room while she is trying to work and also to be polite when he wants to chat. You feel her irritation and yet you see both sides. It is heartbreaking but also very funny!

I have the benefit of working with actors I was initially interested in because of their dramatic chops but what I also had were actors train in comedy. I really noticed it when we were working on that scene. Their timing was just so excellent, and it’s kind of brilliant. And those abilities are what give the film its lightness because it talks about things that are very serious and they are dramatic but I think there’s lightness to that these actors bring and then I hope that I bring. I’m lighter than I was the last time I saw you. I mean “Married Life” was a darker film. And it’s a film about what is hidden. And that was something that was very compelling to me until I was forty.

That is a dark film. It’s about adultery and a husband who plans to commit murder. But it ends in a remarkably sunny way.

We’re all generally struggling lovely people. If you get down to it there’s something touching about each of us. I don’t believe in evil, I believe in the creation of evil.

There’s a very tender scene in “Love is Strange” where we get a glimpse of how sweetly this couple support each other.

They loved each other and they believed in each other. There was a Hal Hartley film made in the 90s called “Trust.” I haven’t seen it since then but I remember one of the characters said that love equals respect plus admiration plus trust. And I’ve actually often thought about those three terms as how they intertwine and how they’re also distinct. The respect is different than admiration and trust is yet another thing. And I’m in a marriage that has those things. But marriage is a legal vessel that this film speaks to but it’s actually not the subject of this film. The subject is intimacy.