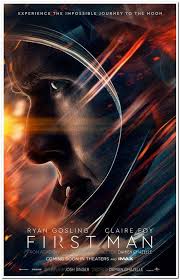

First Man

Posted on October 11, 2018 at 5:54 pm

B +| Lowest Recommended Age: | Middle School |

| MPAA Rating: | Rated PG-13 for some thematic content involving peril, and brief strong language |

| Profanity: | Brief strong language |

| Alcohol/ Drugs: | Alcohol and smoking |

| Violence/ Scariness: | Intense peril, characters injured and killed, sad death of a child |

| Diversity Issues: | None |

| Date Released to Theaters: | October 12, 2018 |

| Date Released to DVD: | January 21, 2019 |

We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

The extraordinary story of the space race that followed has been covered by many books and movies. But none have taken us so literally inside the trip to the moon like “First Man.” Ryan Gosling, working with his “La La Land” director Damien Chazelle, plays Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the moon. Gosling is one of the few actors who could bring such humanity to the famously reserved Armstrong. Chazelle wisely spends much of the movie focusing on Gosling’s face, and he conveys infinite courage, integrity, and dedication, and more. Armstrong did not talk about the tragic loss of his toddler daughter to cancer. When he is asked about whether it affected him in his interview for the space program, he answers calmly that it would be impossible not to be affected. But we see so much in the way he touches her hair, and in the way he thinks of her in an important moment near the end of the film.

When we think of space travel, we tend to think of spacious flying machines like the Enterprise or the Millennium Falcon, with sleeping chambers and holodecks and chess games. This movie takes us inside the actual space capsule, all built with practical (real-life) effects, not CGI and it’s as though they launched a metal container the size of a car trunk with an atom-bomb-fueled catapult, in a process that shakes it up like a paint can at the hardware store. We can feel the pressure on the screws as they jiggle and threaten to pop. And we hear — wow, the sound design in this film, from Ai-Ling Lee — the hum, the rattle, the breathing. Armstrong is always strong, contained, and capable, but this movie gives us the intimacy and vulnerability around him. One of the film’s most powerful scenes is the fire that killed the Apollo 1 crew. A small puff of smoke through the hatch is more telling than a special effects inferno.

We see the modest simplicity of the Armstrong’s home as well, slightly more comfortable once they are in the space program and living near the other astronauts. Claire Foy is outstanding as Janet Armstrong, a very traditional mid-century suburban wife but in her own way as honest and determined as her husband. She insists that he sit down with their sons before the moon voyage to answer their questions about the dangers he was facing.

There are a number of nice touches that remind us of some of the other work that was going on. The interviews touch on the selection process shown in “The Right Stuff.” Kyle Chandler as astronaut chief Deke Slayton draws an illustration that takes two blackboards, an indicator of the unprecedented calculations shown in “Hidden Figures.” The calm, analytical response to unexpected peril reminds us of “Apollo 13.” It is not so much, as in that film, that failure is not an option. What Armstrong says in this film is, “We fail here so we will not fail there.”

“First Man” puts us inside one of the greatest explorations in human history, respecting the technical achievements and the breathtaking scope of the vision, but always keeping it real and personal. Archival footage of people reminding us that many Americans thought that the money for the space program would be better spent in solving the problems at home remind us that arguments about priorities have been around as long as people have had impossible dreams. And this movie reminds us that sometimes impossible dreams should be a priority, too.

Parents should know that this film includes severe risk and peril with characters injured and killed, a very sad death of a child, disturbing images, some strong language, smoking, and drinking.

Family discussion: What made Neil Armstrong the right man for this mission? What do we learn by the way he responds to danger? Why did he bring something special to leave on the moon?

If you like this, try; “Apollo 13,” “The Dish,” and the excellent HBO series produced by Tom Hanks, “From the Earth to the Moon”